This weekend, Jews throughout the world will be retelling the story of our national exodus from Egypt. And in the traditional haggadah reading, both Karaites and Rabbanites recite the following three words from Deuteronomy 26:5: Arami Oved Avi. The most common translation of these words is “My father (“avi”) was a wandering (“oved”) Aramaean (“arami’)”. This is in fact how the Jewish Publication Society has chosen to interpret these words.

There is an interesting debate in the Rabbinic community about what these words mean. But none of the Rabbinic opinions I have come across is fully satisfying. The historical Karaites have a unique interpretation of these words. And that interpretation is also not perfect. At the end of this post, you can vote on the interpretation you believe is the “best.”

Let me preface this by saying that there are actually no halakhic implications to this discussion. Regardless of whose interpretation is correct, it won’t affect your daily lives – or even your haggadah reading.

For background, we are instructed in the book of Deuteronomy to recite the following words when we bring the offering of the first fruits of the land: “Arami Oved Avi.” There are three issues to determine: (i) who is the “arami”? (ii) who is the “avi”? and (iii) what does “oved” mean? As you will see none of the interpretations I identify below is perfect. That is why you will vote on the “best” interpretation – and not the “correct” interpretation.

Let’s first analyze the common translation: “My Father (‘avi’) was a wandering (‘oved’) Aramaean (‘arami’).”

Under this interpretation, the Arami and avi are the same person, and he is described as wandering. The Rabbinic Sage Rashbam believes that Abraham is the Avi – that is Abraham was a wandering Aramaean. The Rabbinic Sage Ibn Ezra believes that Jacob is the avi – that is Jacob was the wandering (or poor) Aramaean.

This translation has 2 problems. First, the ta’amim (i.e., those symbols above and below the words that help us understand the text) suggest that “Arami” and “avi” are not the same person. (In fairness, some exegetes believe that the ta’amim actually support the view that Arami and Avi are the same person.) Second, Lavan is described as an Aramaean in the Torah, but Abraham and Jacob are not. (Abraham had Aramaean relatives, but he himself is not called an Aramaean.)

The Second Most Common Translation: “An Aramaean (‘arami’) [tried to] destroy (‘oved’) my father (‘avi’).”

This translation is based on the events of Genesis 31 in which Lavan chased after Jacob. Under this interpretation, the Aramean is Lavan and the father is Jacob. This is the opinion of Rashi. The perish opinion is also mentioned in Karaite sources.

This interpretation (in my opinion) solves two problems, but it creates a third problem. The two problems it solves are (1) it follows the suggestion of the ta’amim and makes Arami and avi two different people and (2) it correctly identifies Lavan as the Aramaean. The problem it creates though is that the word “oved” here is used as a transitive verb. The word oved in Hebrew is in the “kal” form, and the word in the kal form does not take an object in any of the other 10 or so uses elsewhere in the Tanakh. This makes the interpretation that Lavan tried to kill/destroy Jacob somewhat problematic in my mind.

A Karaite Approach: “With the Aramaean, my father was poor.”

Under this interpretation, the Aramaean is Lavan, and the father is Jacob. And the word “oved” means poor.

This interpretation solves all three problems mentioned above – (1) Arami and oved are now different people, (2) Lavan is “properly” identified as the Aramaean, and (3) the word “oved” does not take an object. However, this interpretation introduces a different problem.

In order to interpret the verse in this manner, you need to pretend the verse has a “bet” in front of the Arami. So it is “ba’Arami oved avi” – “With the Aramaean [Lavan], my father [Jacob] was poor”.

This opinion is reflected in the Karaite commentary of Sefer Ha’Osher, written by Hakham Yaaqov ben Reuven in the 11th century. Sefer Ha’Osher is almost exclusively a summary of earlier opinions (mostly the opinions of Yefet ben Eli). Here is what Sefer Ha’Osher says, which I will translate afterward.

(ספר העושר על פרשת כי תבוא 26:5 עמוד 90 ימין)

ארמי אובד- בעת שבא יעקב אל לבן היה אובד ועני. ד”א היה בלב ארמי לאבד לאבי והוא שרדף אחריו.

“Arami Oved – at the time that Jacob came to Lavan, he was poor and oppressed/suffering. Alternatively, [it means that] it was in the heart of the Arami [Lavan] to destroy my father [Jacob] and it was he [lavan] that pursued him [Jacob].”

As you know, the KJA just released its updated haggadah, and it chose to translate the words Arami Oved Avi in accordance with the opinion, “With the Aramaean, my father was poor.”

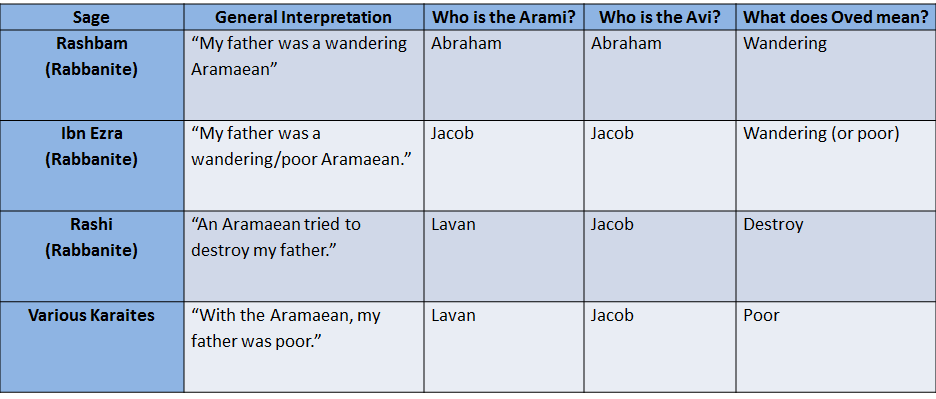

I have summarized these opinions in this chart:

So, let me know, whose opinion do you think is the best?

* * *

Credit must be given to:

(i) Nehemia Gordon, who discussed this verse in his collaborative commentary on each Torah portion. In that commentary, he indicates that he prefers the “perish” opinion to the “wandering” opinion – precisely because the ta’amim hint that the Arami and the avi are two different people. He did not address the opinion that I have labeled as the Karaite approach here;

(ii) a Chabad Rabbi who discussed these verses and opinions with me for hours over Shabbat dinner;

(iii) the orthodox rabbi (of Agudath Israel) whom I study with every week and who discussed this with me on countless occasions;

(iv) Isaac S (a frequent commenter here), who provided me with various opinions from his Miqraot Gedolot;

(v) James Walker and Eli Shemuel for looking up various Karaite sources for me.

How about Arami (Lavan) oved (oppressed by virtually “enslaving”) Avi (my ancestor – Jacob)

That is interesting, but it still has the grammatical problem of “oved”. It cannot take a direct object in Hebrew.

BTW, the Karaite Sage Yefet ben Eli provides the following opinions, which I am summarizing: Oved is an intransitive verb (i.e., does not take a direct object).

“With Laban, my father was destitute.”

“At the hands of Laban (on Mt. Gilead), my father nearly perished.

This second opinion is very similar to yours, but preserves the grammatical structure.

1. I agree with the supposedly minority opinion that Ṭa`amai haMiqra actually support the view that “Arami” and “Avi” are the same person; at the very least, the Ṭa`amim do not determine one way or the other in this matter. Why you are so certain to the contrary eludes me.

2. Are you absolutely sure that the statement “Haya b’Lev Arami Le’Abed Le’Avi” cannot be rendered as “it was in the heart of an Arami [Lavan] to make poor (or “poorer”) my father [Jacob]? If it can, this poses another problem for the Qaraite interpretation.

3. Having stated all the above, seems to me that the Qaraite approach is the most correct given the context; our ancestor (“Avi”) is first poor and oppressed and subsequently taken out of the House of Bondage to a land overflowing with milk and date honey, where we are blessed by YHWH with assorted goodness.

1. If you look at how the taamim are coupled “arami” has a slight pause after it. And “oved avi” are coupled together. Look at Vayered Mitzrayim afterward. Those are coupled together in the same way that Oved and Avi are coupled together. This is not conclusive, but it is indicative.

2. This is possible, and I am not sure why this poses a problem for the Karaite Interpretation. BTW, the Karaite Sage Yefet ben Eli provides the following opinions, which I am summarizing: Oved is an intransitive verb (i.e., does not take a direct object).

“With Laban, my father was destitute.”

“At the hands of Laban (on Mt. Gilead), my father nearly perished.

3. Agreed.

אָבֵד—-Lost

Any relation to work hard, oppressive would have Ayin as the base letter, not Aleph as in being lost or wandering as our father who got his sons wives from

פדן ארם Padan Aram. Avraham

Padan Aram was were Abraham first after they left Ur Casdeem/City of the Chaldeans and there his brother Nahor settlerd. Betuel was Nahors son, Lavan was Betuels son. There is nothing here other the wanderings. Though you might question if God told Avraham to go to Canaan then how he go lost–אָבֵד unless he was wandering around Canaan without any instruction so you could say he was lost till later when God resumed communication.

Abraham’s roots are Aramaen. He was a wanderer (a shepherd), preferring to leave his birth place and go to the land where God command him to settle.

The lands of Aram stretched from the eastern border of Israel to the Zagros mountains in the East. Aram was the dominant son of Shem- the only one worthy of lineage mention in Torah- aside Arfaksad from whom the Israelites descended. Aram was such a dominant family that Nahor, Avraham’s brother, named his sons after Aram and his son Uts. Since Avraham, Yitschaq, and Ya’aqov were not a nation, until the birth of the Nation of Yisrael, it seems natural that Avraham and his sons would have been considered Arami- just like his brother’s family. Ya’aqov, the Arami, was indeed perishing- there was a famine in the land which caused him to send his sons to Mitsrayim- setting up the events of the Exodus.

For this reason, we were commanded to remember this when we deliver our first-fruits. A miracle from start to finish.

וַיַּ֣רְא יַֽעֲקֹ֔ב כִּ֥י יֶשׁ־שֶׁ֖בֶר בְּמִצְרָ֑יִם וַיֹּ֤אמֶר יַֽעֲקֹב֙ לְבָנָ֔יו לָ֖מָּה תִּתְרָאֽוּ׃

וַיֹּ֕אמֶר הִנֵּ֣ה שָׁמַ֔עְתִּי כִּ֥י יֶשׁ־שֶׁ֖בֶר בְּמִצְרָ֑יִם רְדוּ־שָׁ֨מָּה֙ וְשִׁבְרוּ־לָ֣נוּ מִשָּׁ֔ם וְנִֽחְיֶ֖ה וְלֹ֥א נָמֽוּת׃

The idea of the participle, Oveid, carried the same meaning in Arami Oveid as is used among the Arabs when referring to the vanishing/perishing tribes of Ancient Arabs of Qahtan (Yoktan)- Arab Ba-idat (a participle). The alef in the Arabic is a metathesis- which happened in many North Semitic to South Semitic roots.

As a linguistic matter, we know that Hebrew at one point had case endings like Arabic, so maybe when we’re dealing with a verse this old, the interpretation hinges on which case the word arami is in. If it is in the nominative case, then avi and arami would be the same person, but if it is in the genitive/oblique case, you could translate it as “My father was poor with the Aramean” or “My father was poor from (due to) the Aramean”. Since the t’amim suggest that avi and arami are different people, I would go with the latter interpretation. Maybe the ones who fixed the t’amim knew about the case endings and tried to use the t’amim to fill in the information that was lost when the endings were dropped.

Laba. and Abraham had the same Patelrineal ancestry going back to Terah, if one can be called an Aramean so can the other. And Laban’s sister was the mother of Jacob.

Abraham came from Urkesh not the Sumerian Ur.

It would only be genetive or dative in two ways: 1) with a preposition on Arami or 2) in a construct chain. Neither exist in the Text.

Maybe it is a case of weaker subordination to the verb, like in the sentence “Yomam hashemesh lo yakekha”. Couldn’t you say that “yomam” functions as a dative even though there is no preposition?

My mistake, “yomam” is always an adverb.

You are right that in general, looser subordination to the verb without a preposition usually occurs only with a construct chain. However, there are exceptions. In 1 Kings 8:34, Shlomo says to G-d “תשמע השמיים, וסלחת”, which is translated as “May you hear in heaven, and forgive”. There is no preposition there, but the “in” is inferred from context. Given the fact that ארמי comes right after the verb אובד, I still think that it’s plausible that this is one of the rare cases where weaker subordination occurs without a preposition, and so it is legitimate to read it as “With the Aramean, my father was poor.”

The key to understanding the passage is 1 Kings is this:

וְשָׁמַעְתָּ אֶל־תְּחִנַּת עַבְדְּךָ וְעַמְּךָ יִשְׂרָאֵל אֲשֶׁר יִתְפַּֽלְלוּ אֶל־הַמָּקוֹם הַזֶּה וְאַתָּה תִּשְׁמַע אֶל־מְקוֹם שִׁבְתְּךָ אֶל־הַשָּׁמַיִם וְשָֽׁמַעְתָּ וְסָלָֽחְתָּ׃

“And You shall listen to the place of your dwelling, to the Heavens- You shall listen and pardon.”

The subsequent phrases are not, You shall hear in Heaven, but rather You shall listen to the heavens as is evident from the initial preposition (to) in relation to the Heavens. In all the subsequent passages, Heavens stands as accussative.

The participle oveid follows the word Arami.

As a side-note: What does it mean for G-d to listen to the Heavens?

Interesting.

I’m a convert and am currently investigating Teimani, Mizrachi, and Sephardi practice, but received the first decade of my Jewish instruction from Reform and Orthodox Rabbinic Judaism. For a short time I also tried to look into Beta Israel practice (Ethiopian/Eritrean), but it’s hard to find material in English, so I abandoned that path, at least until and unless I can find a teacher and/or improve my other languages immensely. I tell you this just so you’ll be able to track which communities are telling which stories/interpretations. From where I stand, there are a vast number of interpretations that are valid, and one of those valid paths is Karaism. We need all Jews in k’lal Yisrael.

Anyway.

“Arami oved avi” was always translated, in my rather limited experience, as “My father served (or “serves”) an Aramean.” So the servant, the oved, was Ya’akov, and the Aramean was Lavan. Or if taken as present-tense, then it suggests that my father (or my ancestor, or my progenitor) continues to serve someone in the same manner as Ya’akov served Lavan. We have many a discussion about this, but I’d never heard ANY of the above interpretations before. This Pesach will be an extremely interesting dinner conversation with these additions to the idea base!

As far as I am aware, this would be a mistranslation. The word “oved” here is with an Aleph, not an Ayyin. So I am not sure why it would be understood as “servant.”

Interesting. I wonder when that error crept in. No, wait, I wonder which is the error — the interpretation of oved being wrong according to the spelling, or the spelling of oved being wrong according to the meaning it was supposed to have. Only one can be true.

Never mind, actually. I already know what’ll be said. The Reformim will say “That’s a fascinating subject for a drash,” and there’ll be a drash. And then the Orthodox will say “There are no errors in the whole of the Torah and all of canonized literature, G*D wrote it by directly moving Moshe’s hand and therefore it’s perfect as it is,” and that’ll be that.

I agree with Judith. But rather than say it is a scribal error, I say it is a phonetic drift leftover from when it was a verbally transmitted story. Alef and ayin were essentially interchangeable, and when these stories were finally written down, probably by Ezra the Scribe, it could only be guessed as to how the phonetics were originally spelled. The problem with literacy is that it canonizes any errors, and that is the sin we have labored under.

Personally I understand ארמי אבד אבי to mean “my founder was a genetic prospector”, where פדן ארם is the inheritance of Noach to Abraham patrilineally. Aram was never a geographic location, but a royal family. During Avram’s journey to Egypt they were delayed in northern Assyria, where those that remained settled the region and were later called Arameans. There is DNA evidence for this in the form of an unexplained cluster of male Haplogroup J2 in the area today.

In my version of the story, Abraham, or rather Sarah, journeyed to Egypt with a clever plot to trick Pharaoh into being an unwitting sperm donor in a eugenics program. Thus the cockamamie story about the results of Sarah’s encounter is clever disinformation to hide the true origin of the Israelites.

If, for the sake of argument, we accept that the Alef present in the current Text should have been an Ayin, that would make the initial clause read

ארמי עבד אבי וירד מצרימה

The עבד could only be one of these possibilities:

1) pa’al perfect עָבַד ‘AVaD- served

2) pa’al active participle [written defectively] עוֹבֵד ‘OVeiD- [is] serving

3} pa’al infinitive construct עֲבֹד ‘AVoD [to] serve

4) pi’el perfect עִבֵּד “IBBeiD- put to service/work

5) pi’el infinitive ַַabsolute/construct עַבֵּד ‘ABBeiD [to] put to service/work

6) pu’al perfect עֻבַּד [be] put to service/ [be] worked

7) pa’al/pi’el/pu’al imperitives- serve!/work!

This would render the initial clause in one of the following ways:

1) pa’al perfect- An Aramean served my father and he went down to Egypt…

2) pa’al active participle- An Aramean is serving my father and he went down to Egypt…

3) pa’al infinitive construct- An Aramean [to serve] my father and he went down to Egypt…

4) pi’el perfect- An Aramean set my father to work and he went down to Egypt…

5) pi’el infinitive absolute and construct- An Aramean [to] set my father to work and he went down to Egypt…

6) pu’al perfect- An Aramean [to be] put to work my father and he went down to Egypt…

7) imperatives, as we can all agree, would never fit the context.

I believe the current text is the correct one and that the Moasoretic pointing- in this place- is also correct as a pa’al active participle.

As I attempted to explain above, since the Israelites were not a nation, until the birth of the Nation of Israel, it seems natural that Abraham and his sons would have been considered Arami- just like his brother’s family. Jacob, the Aramean, was indeed perishing- there was a famine in the land which caused him to send his sons to Egypt- setting up the events of the Exodus.

For this reason, we were commanded to remember this when we deliver our first-fruits. A miracle from start to finish.

The idea of the participle, Oveid [אבד], carried the same meaning in Arami Oveid as is used among the Arabs when referring to the vanishing/perishing tribes of Ancient Arabs of Qahtan (Yoktan)- [العرب البائدة] al-Arab al-Ba-idat (a participle). The alef in the Arabic is a metathesis- which happened in many North Semitic to South Semitic roots.

Laban was the uncle of Jacob, the brother of Rebekka, Jacob’s mother. He was from the same paternal line as Abraham- neither were descended from Aram, but were from Arfaksad, the brother of Aram. Although Laban tricked Jacob into working longer than Jacob planned, he never sought to harm Jacob.

The passage above referred to an event, long after the time Jacob left the service of Laban- just after Joseph was sold to Egypt as a slave. There was a famine in the Levant and there was no food in Canaan. Jacob, seeing his remaining sons idle, asked:

וַיַּ֣רְא יַֽעֲקֹ֔ב כִּ֥י יֶשׁ־שֶׁ֖בֶר בְּמִצְרָ֑יִם וַיֹּ֤אמֶר יַֽעֲקֹב֙ לְבָנָ֔יו לָ֖מָּה תִּתְרָאֽוּ׃

וַיֹּ֕אמֶר הִנֵּ֣ה שָׁמַ֔עְתִּי כִּ֥י יֶשׁ־שֶׁ֖בֶר בְּמִצְרָ֑יִם רְדוּ־שָׁ֨מָּה֙ וְשִׁבְרוּ־לָ֣נוּ מִשָּׁ֔ם וְנִֽחְיֶ֖ה וְלֹ֥א נָמֽוּת׃

Now when Jacob saw that there was corn in Egypt, Jacob said unto his sons, Why do you look one upon another? And he said, Behold, I have heard that there is corn in Egypt: go down [same verb as used in our firstfruits confession] there and buy for us from there; [that we may continue to live, and not die]. And Joseph’s ten brethren went down to buy corn in Egypt. But Benjamin, Joseph’s brother, Jacob sent not with his brethren; for he said, Lest peradventure mischief befall him. And the sons of Israel came to buy corn among those that came: for the famine was in the land of Canaan. Genesis 42:1-5 brackets are mine for emphasis.

It was this event which prompted the children of Jacob to enter Egypt and which fulfilled the dream Joseph had- that his family would serve him. This was also the beginning of the prophecy God spoke to Abraham in Genesis 15- that his children would serve a nation for 400 years and return to Canaan in the 4th generation. Basically, this was the event which led to the miracle of the Passover and Exodus story.

This commandment, which demanded we speak these words when we offered the firstfruits, was intended that we remember the fulfillment of God’s promises, prophetic fulfillment, and the miracle of the Passover. Jacob, the Aramean, was not wandering astray, nor was he being pursued by an Aramean who wanted to destroy him; on the contrary, Jacob, the Aramean, was in danger of starvation and the annihilation of his family.

Pingback: A Karaite Passover Resource Guide - For Rabbanites - A Blue Thread