A few weeks ago, I mentioned how Azriel Kowtek shared her passion for blue fringes and tying tzitzit with several of us who attended the KJA’s shavuot gathering. Last week, I wrote about the importance of reviving Karaite literature. And this past Shabbat, Rabbanite Jews read the Torah portion related to the commandment to wear blue fringes. [1.]

In the Rabbinic tradition, women are not required to wear blue fringes. Let’s see what the early Karaite literature says on the topic.

I’m a Karaite; I have to start with the text of the Tanakh.

So let’s see what the Torah says: “Speak to the children of Israel [b’nai Yisrael], and tell them, they shall make for themselves throughout their generations fringes in the corners of their garments, and that they put with the fringe of each corner a thread of blue. And it shall be unto you for a fringe, that ye may look upon it, and remember all the commandments of the LORD, and do them; and that ye go not about after your own heart and your own eyes, after which ye use to go astray; that ye may remember and do all My commandments, and be holy unto your God.” Numbers 15:38-41 (JPS Translation.)

The key here is (with respect to this verse) whether “b’nai Yisrael” means “children of Israel” or “sons of Israel.” Both are theoretically possible – though, you’d have to give me a good textual (or even cultural) reason why the commandment would be directed only to the men. But let’s see what the Sages say.

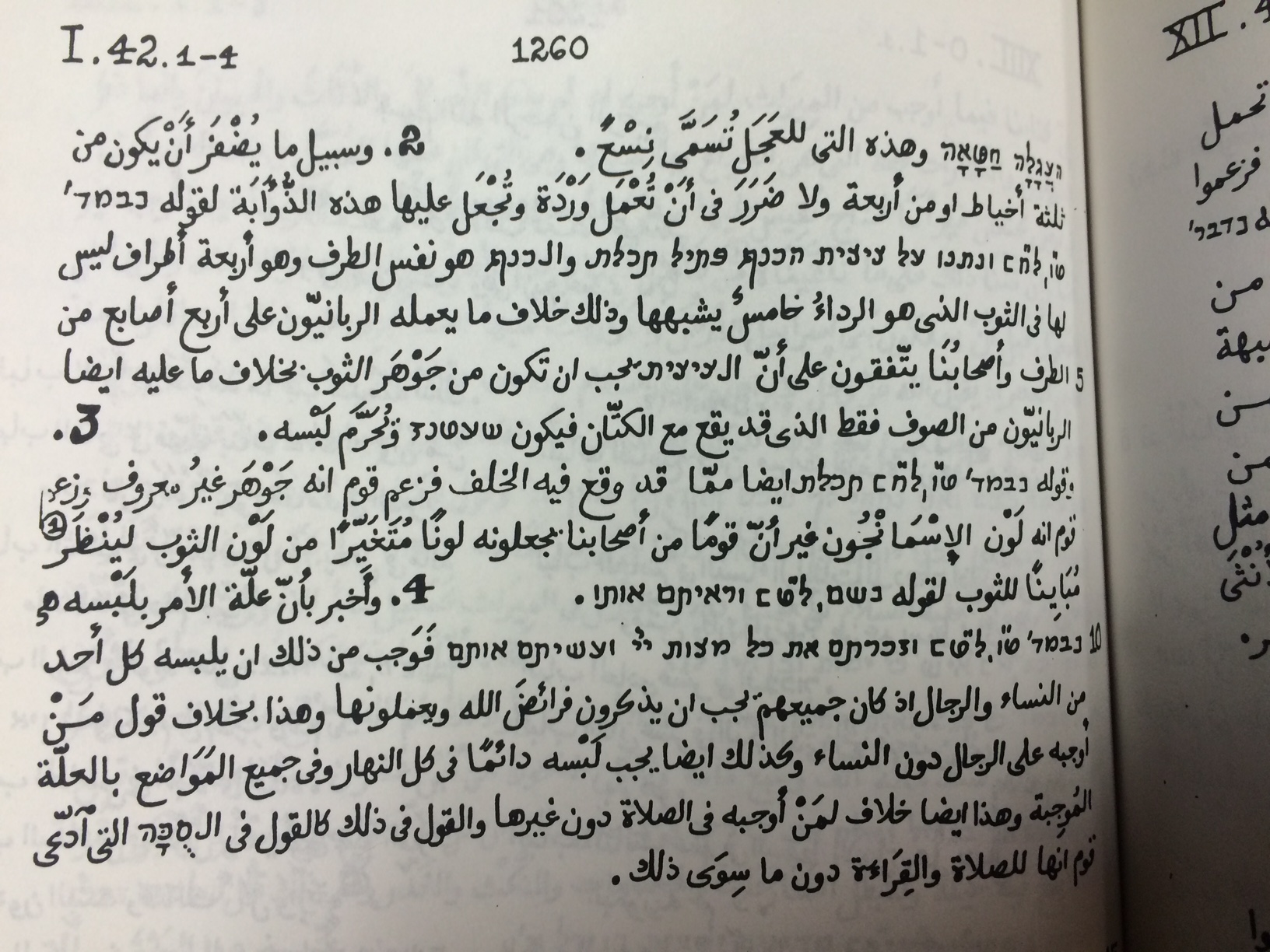

The earliest Karaite source of which I am aware to discuss this topic was Hakham Yaqub al-Qirqisani, who lived in the first half of the 10th century. He wrote Qitab al Anwar w’al Maraqib (“The Book of Lights and Watchtowers”), his magnum opus, in Judeo-Arabic; and Professor Leon Nemoy (Z”L, pbuh) transcribed the work by hand into Arabic. According to Nemoy’s rendition, Qirqisani held that women are obligated to wear tzitzit.

The pertinent part of sentence 4 says, “I inform that the reason for the command to wear it is: ‘…and remember all the commandments of the Lord and do them (Num 15:39)’. So out of this it is obligatory to be worn by everyone of the women and men since all of them are obliged to remember G-d’s obligations and do them and this is different from he who says that it is obligated on men and not women.” (Translation adapted from Acting Rav Joe Pessah.)

Qirqisani was not the only Karaite Sage who held that women must also wear blue fringes. According to Mikdash Me’at, late 10th/early 11th century Karaite Sage Levi ben Yefet also held that women must wear tzitzit. And Hakham Moshe Firrouz recently informed me that 12th century Karaite Sage Yehudah Hadassi also held that women must wear blue fringes. [2.]

I share these early Karaite opinions not because they are “correct”. These Karaites could be wrong on this issue or on every issue.

I share them because all of this literature is virtually lost and unavailable to most Jewish scholars and students – including historical and new Karaites. And we need to change that. Exposure to new ideas – even if we ultimately reject them – sharpens our own views of halakha and tradition. And it enables us to live out an important part of the Karaite creed: to test our opinions against the opinions of others.

* * *

[1.] The Karaite and Rabbanite parashiot do not always line up. For example, this past weekend in Daly City, we read parashat Korach.

[2.] קשירתו כי גם היא בת ישראל מבני ישראל בדומה במצות ציצת: קול צווי דבר אל בני ישראל ואמרת אליהם ועשו להם ציצת: קדושת מצותו גם האשה בקיום כל המצות ככתוב וראיתם אותו וזכרתם את כל מצות ה’ ועשיתם אותם כצווי צורך: “רמיזתו ככתוב הקהל את העם” האנשים והנשים והטף וגרך אשר בשעריך: רפידתו למען ישמעו ולמען ילמדו ויראו את ה’ אלהיכם ושמרו לעשות את כל דברי התורה הזאת תורתך:

(אל”ב יג’, אות ק’)

Setting aside theological arguments for the moment, most languages default to the masculine when saying things that are gender neutral, including Hebrew. Historically, that has been the case with English as well. So before one gets into religious interpreration, it is generally safe to assume that commandments written in the masculine voice apply to both sexes unless something about a commandment specifically excludes or exempts women.

Excellent point. Another example is if whether a translation should be ‘sons of Israel’ or ‘children of Israel’. The translation would be; if what preceded was talking about Jacob’s twelve sons, then the ‘sons of Israel’ would be the correct translation. This is because a specific gender has been previously established. If no specific genders, specific person or persons, or feminine specific prefixes or suffixes, are given then the ‘children of Israel’ would be the correct translation. This is true in all languages, including ancient Hebrew (the original language and language of the Creator).

The only statement in that Torah verse, that I am unclear of, is to ‘wear it on the corners of your garment’. The style of clothing has obviously changed; and a circle has the same starting and ending point; so I wear only one tsee tsith. I know that orthodox Jews have a special garment to wear them on four corners. On my part I am obviously making an assumption that as long as I wear them, no matter the quantity, it is reminding me of the Commandments and therefore fulfilling its purpose.

Reminds me of something I once read where a guy said he only wears one and it hangs over his wallet pocket, so that he pauses to think of the Commandments before he makes any purchases. I like to wear mine to the front where I can see it.

Tom- since the Torah does not contradict irrefutable and well established scientific findings and does not even attempt to argue that Hebrew was the first or original language of humankind, this notion must, at the very least, be consigned to the den of unproved theses. There is not even a shred of historic evidence that this was the first language ever used by human beings.

I have also examined the theses, is Hebrew the original language, to see if there is evidence that it is Hebrew. It has been awhile but I will try to reach back into my brain’s ROM to remember.

One of the first to come to mind is that the names of the people in the Garden mean something in Hebrew; they do not in Chaldean, or Egyptian, etc.

The language and the structure of the Hebrew in the Torah is unadulterated by other languages; i.e it is pure; unlike the worse case example of English. There are not any foreign adopted words in Torah Hebrew; notice I did not say the TANAKH. Many foreign gods have Hebrew names; Adonis is from Adon (lord in Hebrew) yet is a Greek god; the Cannanite god Molech was in reality called Melekh (ruler in Hebrew; the Rabbi’s changed the vowels for religious reasons); Rah the Egyptian and Dagon the Philistine god are other examples of Hebrew words that became the names of foreign gods, etc.

The meaning of words in Hebrew are very specific. For example; there are two Hebrew words for ‘I’. One means I (in relationship to you) the other means I (as apposed to you). There are three Hebrew words that in English mean ‘error’. But they each mean different types of error. The main point is that Hebrew is a very concrete language; as opposed to most others that are very abstract.

The Phoenicians neighbors of the Israelites used Hebrew in their merchant trade dealing and record keeping and so the written language was picked up and adopted by the Greeks for their abstract written language.

The Hebrew language is based on a three consonant root system that does not require vowels. Within this three root system are many two letter roots; and they all have the meaning of their words matching the original pictographic letters.

The Creator spoke to Moses and the people in Hebrew at Sinai and all the prophets wrote in Hebrew; with some exceptions . (I personally chose to hold no value to those writings that are the exceptions).

I hope this has primed the pump and that this will help you to give thought to the possibility of Hebrew being the original language; and even adding to my list.

Thanks Tom for this response.

It is a widespread error to consider the original Hebrew alphabet pictographic.

But much more to the point, you err in considering the Torah’s Hebrew pure and unadulterated, since at least two foreign loan words exist which are “Se’or” (leaven) and She`aṭnez (a mixture of wool and linen).

That the names of the people in the Gan `Eden mean something in Hebrew but not in other languages is no proof; perhaps the Torah is calling them by their Hebrew names, namely translating their names in some other language to Hebrew.

Therefore, there seems to be no concrete evidence for the argument that when humans began using a language for the first ever, it was Hebrew.

Zvi, I responded on this blog because there was not a reply button on your last comment to our conversation.

The rule of translation is that proper nouns are transliterated and not translated. Assuming that the rule might have been broken it should be observed that every name in the Torah means something in Hebrew. As often as not the meaning of the names add to further understanding of the narrative of the text. It is interesting to note that the first name that doesn’t have a meaning in Hebrew is Nimrod.

And yes, I admit to generalizing when I said that there were no foreign loan words in the Torah (first five books). However, compared to the rest of the TANAKH they are rare. Also I do not believe that the text has remained 100% pure through the thousands of years since it was originally written. The change to the Babylonian script alone certainly produced its own errors. However, it appears to be remarkably true to what the original might have been. Unfortunately it is too long of a subject to cover here. Also I always try to hold to the scientific method and will always consider a challenge that my premises are false.

As far as the original Hebrew alphabet being pictographic; I suggest you check into the works of Jeff Benner on YouTube.

Thanks for the stimulating conversation. It is, unfortunately, rare today.

Wow!!! A few months ago you (or some other Qaraite of Egyptian extraction) claimed that Ḥakham Lewi ben Yefet was the ONLY classical Qaraite sage that held that women must wear Ṣiṣiyot.

Now we know that _three_ classical Qaraite Ḥakhamim maintained this.

I feel much better now about medieval Qaraite Sages

I think I am familiar with the discussion. If it was me, I was repeating that it was the only sage that I knew of. But yes, at least three.

“Tying it, since also a daughter of Israel is of the Children of Israel, similarly as in the Ṣiṣit commandment: a commanding voice ‘Speak to the Children of Israel and say to them that they shall make themselves tassels: His commandment’s sanctity [spans] also the woman in keeping all the commandments, as written ‘that you may look at it and keep-in-mind all the commandments of YHWH and observe them’ as an obligatory command: “its insinuation as is written assemble the people” the men and women and the little-ones and your sojourner that is in your gates: its lining ‘in order that they may hearken, in order that they may learn and have-awe-for YHWH your God, to carefully observe all the words of this Instruction, your Torah’:”

Translated by Zvi.

Where is there a w in Hebrew, it is a vav , explain that please?

the theory – and I agree with the theory – is that it used to be waw (not vav).

So I’ll throw my rabbinic brain into this….

In Rabbinic Judaism women are exempt from positive, time-bound mitzvot.

The passage says one must wear them to “u z’chartem et KOL mitzvot hashem…” Two thoughts. Does Karaism also exempt women from the mitzvot above, and if so, does the word “kol” exempt women from wearing tzitzit?

On the other hand (or corner) there’s also a discussion regarding why we read this passage in the Shema at night, when we don’t typically wear tzitzit, that it’s included as a reminder of yetziat mitzrayim, in which case, women would be obligated. Or only at night 🙂

Karaism does not exempt women from these mitzvot. The Karaite Sages believe that we are required to wear tzitzit all the time. (That is mentioned in the second half of sentence 4 of the Kirkisani quote – the translation of which I did not provide.)

The rule of נשים פטורות ממצוות עשה שהזמן גמרא is made up by the תנאים. No where throughout the Tanach do we find such a concept. If you are orthodox ( like I am then almost all of the stuff you here is made up by rabbis.) Forget about everything you know, and start reading the Tanach without rabbinic type of interpretation.

גרמא*

Hear*

Isaac, I’m aware that there’s nothing in Tanakh about women being patur or chayyav, I was wondering whether or not all mizvot are incumbent upon all in Karaite Judaism.

I’m not orthodox, and I don’t accept that what the rabbis say is mi Sinai, but that’s another discussion.

If Karaite women are obligate to put fringes on their cornered garments, that might suggest that all of a women’s scarves and shawls, or perhaps even a skirt that has small slits in the hem, would require tzitzit. What about a man in a colder climate who wears a scarf in the winter? Is an accessory a garment?

The Torah says גדילים תעשה לך על ארבע כנפות כסותך אשר תכסה בה. However that can’t mean on EVERY covering because the Torah says that the point of wearing these things is וזכרתם את כל מצוותי ועשיתם אותם. That would be able to be fulfilled with just wearing one of them. Wearing more is unnecessary seemingly.

מצוות ה׳ ועשיתם אותם*

I think you can argue it only applies to the outermost garment – because the commandment refers to the kesut.

כסות comes from the root word כס, so without my prior argument, any type of garment, no matter where it covers should be included in the obligation?

Isaac, are you referring to wearing tzitzit on only one corner of something based on the text in Bamidbar? That text is plural, “al kanfei vigdayhem.”

The other question is, does this suggest that there is a requirement to wear a four cornered garment?

There are several issues implicated:

(i) Is the commandment to wear it on our outer garment (kesut), regardless of what that garment is? Under this theory, the words al kanfei vighdayem merely describe the clothing of the day, and are not limiting factors.

(ii) Is the commandment to wear a four-cornered garment so that we can fulfill the literal application of the commandment, i.e., to wear tzitzit on the wings of the garment?

(iii) Is the commandment to wear tzitzit *only* when wearing a four cornered garment?

In the TANAKH I find the word Torah (singular); but have never been able to find the word Toroth (plural). Kind of makes a person go hummm…..

I also do not find the ‘Greek’ words Synagogue or Sanhedrin. If there are ancient Hebrew words for these Greek institutions then why are they not used ; rather than the Greek words?

That’s not correct. The Tanakh does have the word torot in the plural. See leviticus 26:46. There are others as well.

Thank you for your response. I humbly stand corrected. I will definitely be doing further research.

Because כס means cover. So that would imply any covering.

At first I would have said because no gender was implied but after reading, aren’t we all, men, women and children, obligated to remember and obey the commands of Yehovah? As a woman, they not only help me to stop and remember when faced with challenges but they also remind me I’m not alone in my choices. Its not about standing out but about standing strong.

There are two points here. A) What was the actual practice of Karaite women over the centuries? If they did not wear tzitzit, what was the reason?

B) Rabbinic halacha does not FORBID women from wearing them, but EXEMPTS women from the obligation because they are exempt from all positive commandments dependent on specific times of fulfillment unless otherwise indicated.

C) Whatever the Karaite practice, is it based on reliance on sages interpreting the law as a tradition from Sinai?

Pingback: The Karaite Press is a Small Dream Come True - A Blue Thread

Hi Shawn, I’m wondering if it’s possible to buy some sisith from you.

Thanks, from Avi

Avi, please send me an email to Shawn@abluethread.com, and I will put you in touch with people who can sell them to you.

I think Karaites are mistaking making their fringes like girls’ hairs twined.

Look at Torah!

Deuteronomy 22:12 says in general about fringes, she doesn’t say how to make Tzitzit. She just says to twist threads (“Gidilim”) on four corners of one’s garment.

Numbers 15:38 says to make fringe (“Tzitzit”) on four corners. “Tzitzit” is just threads attached to a garment with a knot. Then she says to put a blue thread (“P’til”) above and around a group of threads (“Tzitzit”) to unite them together. A blue thread (“P’til”) must lay above, not intertwined like Karaites do.

What is “P’til”? It is just a blue thread to round and knot above to protect something in Numbers 19:15 and Genesis 38:18, 25.

Though, the word “P’til” means to round something above to protect and unite, it may be used in opposite sense to leave or corrupt in Deuteronomy 32:5.

Thus, Rabbinic (exactly Ashkenazic) way of making Tzitzit with a blue thread is according Torah, not Karaites’ mode.

A few observations. This of course applies to the tallit, but even the eminent Rabbit Soloveichik opined that there was no reason a woman could not to wear one if she chose to. Extrapolating to tzitzit is therefore logical.

In the Rhineland during early medieval times, women conducted their own (separate) service and read from the torah so the impermissibility in Orthodox circles nowadays, as well as the separation of the genders, is relatively recent among Rabbinic Jews and has no legal basis beyond the accretion of tradition and habit; all were called to listed to the recitation of the Law at Sinai, without distinction to sex.

As far as the blue thread, I do take exception with it being simply blue; tekhelet has come to be synonymous with blue but if simple blue were intended, it would have been called that in the tanakh, yet it is not. Tekhelet had a very specific meaning in antiquity (as did argaman) going beyond the actual color itself and to its sourcing. Archeological evidence of caches of Murex shells in Jerusalem’s priestly quarter points to this and not just the color itself. That the bible does not speak directly how the dye is acquired, we should look at how it was obtained in antiquity.

As to the knotting of the tzitzit, there was never a ‘standard’ in Rabbinic Judaism, only interpretations & recommendations and no single one reckoned more valid than the next.

But it also does not say a women is required either, we do not wear garment like then, so when they came up On wearing a tallit kattan. With then on it, wear in torah does it tell us how to tie them, how do we know the blue that is used is kosher?