I recently discovered something beautiful. There is an error in the traditional Karaite siddur. It may sound strange to call an error beautiful, but I really mean it. The Karaite community has gone to great lengths to preserve – what is in my opinion – the wrong side of a mostly obscure debate over a single letter in a word in the Book of Chronicles.

I only first understood that this debate even exists two months ago, as I was working on a learner’s edition of the erev shabbat prayer book for the American Karaite community.

You can also give me your opinion on what I should print in this new edition of the siddur, by voting in the reader poll.

Let’s start with some background with two very similar verses: 1 Chronicles 17:20 and 2 Samuel 7:22.

The Leningrad Codex on 1 Chronicles 17:20 and 2 Samuel 7:22

Here are the two verses as they appear in the Leningrad codex.[1]

- 1 Chronicles 17:20:

יְהוָה֙ אֵ֣ין כָּמ֔וֹךָ וְאֵ֥ין אֱלֹהִ֖ים זוּלָתֶ֑ךָ בְּכֹ֥ל אֲשֶׁר־שָׁמַ֖עְנוּ בְּאָזְנֵֽינוּ

LORD, there is none like you and there is no god, aside from you according to (bekhol) all that we have heard with our ears.

- 2 Samuel 7:22:

עַל־כֵּ֥ן גָּדַ֖לְתָּ אֲדֹנָ֣י יְהוִ֑ה כִּֽי־אֵ֣ין כָּמ֗וֹךָ וְאֵ֤ין אֱלֹהִים֙ זֽוּלָתֶ֔ךָ בְּכֹ֥ל אֲשֶׁר־שָׁמַ֖עְנוּ בְּאָזְנֵֽינוּ

Therefore, you are great, Adonai, LORD, for there is none like you and there is no god, aside from you according to (bekhol) all that we have heard with our ears.

These verses are virtually identical because they record the same story – one of David’s prayer after wars and surviving assassination attempts and becoming King of Israel.

(As noted below, even though the Leningrad Codex contains bekhol twice, the Masora Gedola clearly tells us that it should be “bekhol” in chronicles, and “kekhol” in Samuel.)

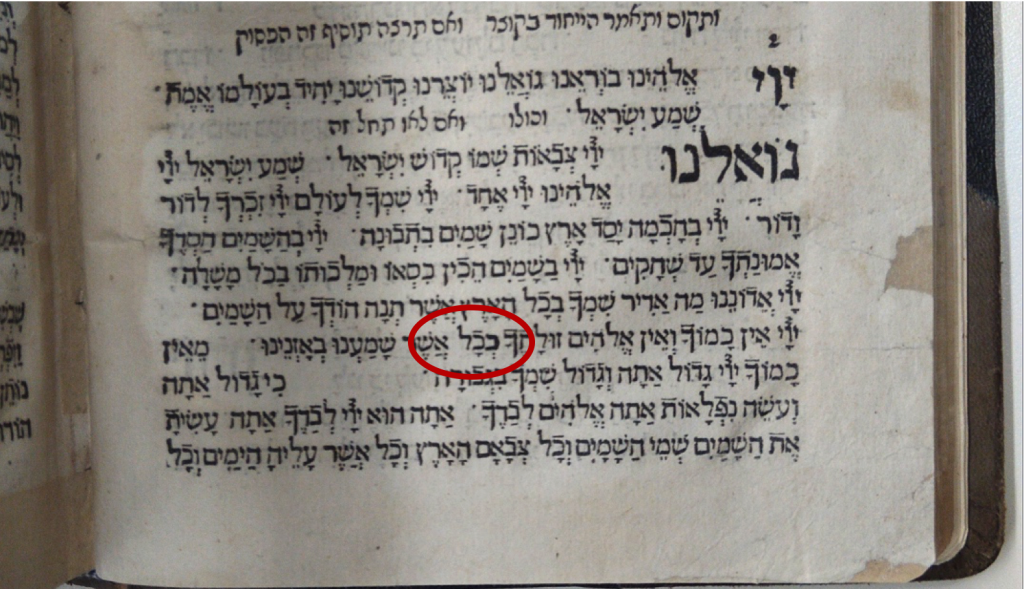

The Karaite Siddur on 1 Chronicles 17:20

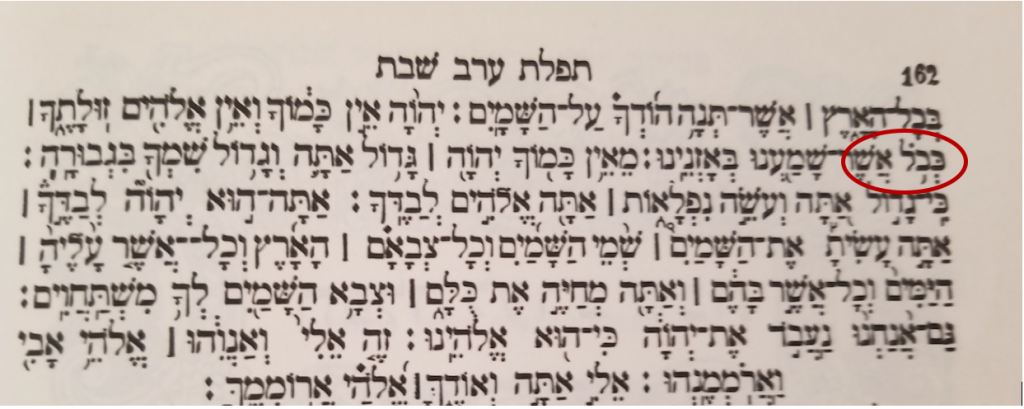

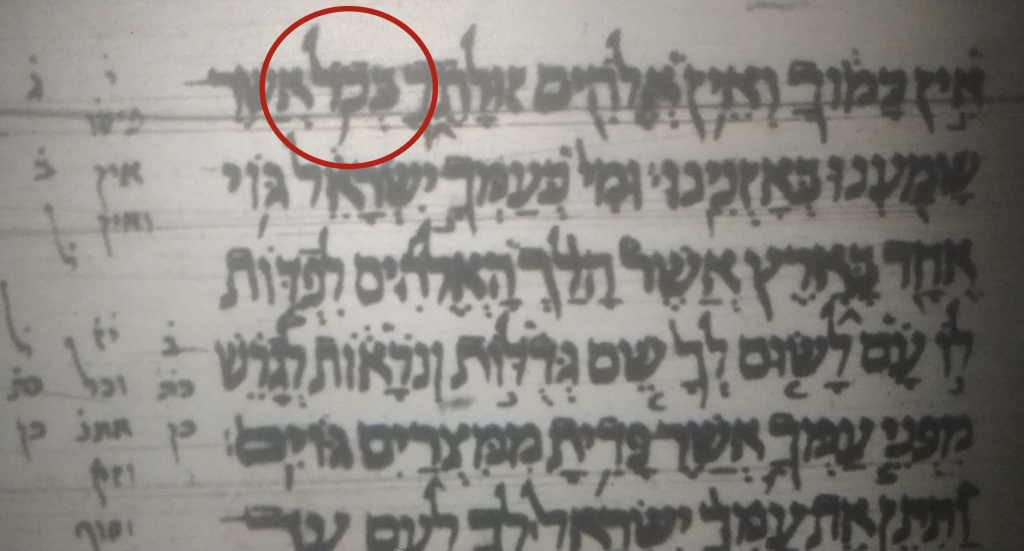

Now here is what is in the Karaite siddur printed in Vilna in 1891 in a passage containing the verse in Chronicles.

Uh. Oh.

You can see that this Karaite siddur (and it is *not* an anomaly or an accident) has kekhol instead of bekhol for 1 Chronicles 17:20. That is, even though the Leningrad indicates that the verse should contain the word bekhol, the siddur has kekhol.

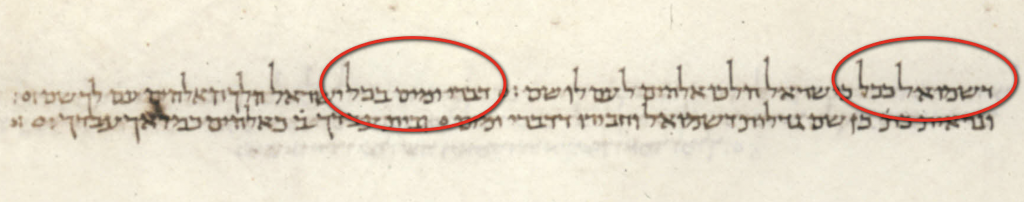

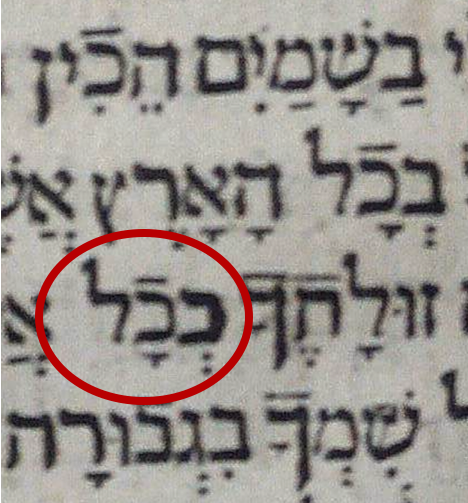

Just to drive the point home that the preference for kekhol over bekhol is intentional and an old one – look at this image of the printing of this verse in the Venice Karaite Siddur, printed in 1528.

The Venice Karaite Siddur seems to have printed “bekhol” and someone “corrected” it by hand to “kekhol.” Click image to enlarge.

And here is the same image zooming in on the word in question – notice how the initial “kaf” in kekhol looks very different from the second kaf.

This particular photograph is of a copy of the siddur currently housed in the National Library of Israel, in Jerusalem. In 1715, this copy was in the possession of the Karaite Jewish community of Chufut Kale, in Crimea; at some point between 1715 and 2017, it arrived in Jerusalem.

You can see that the initial printing (almost certainly read) bekhol and someone changed it to kekhol by hand. Of course, we don’t know when the change was made – but this does show you that there was an older trend in Karaite siddurim to read the verse as kechol (and not bekhol, as it appears in the Leningrad Codex).

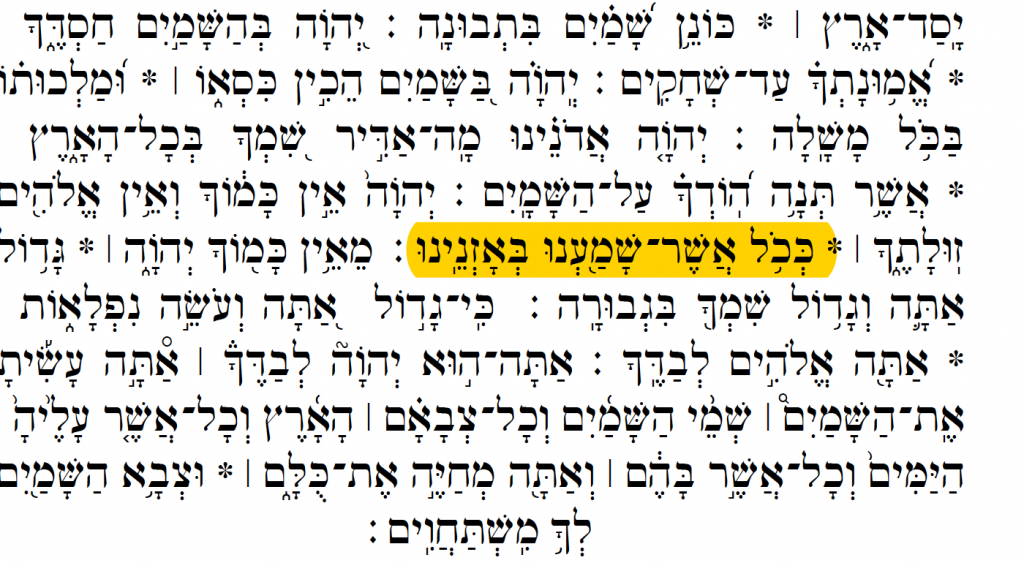

Examining the Evidence for Bekhol: The Leningrad Codex’s Masora Gedola on 1 Chronicles 17:20

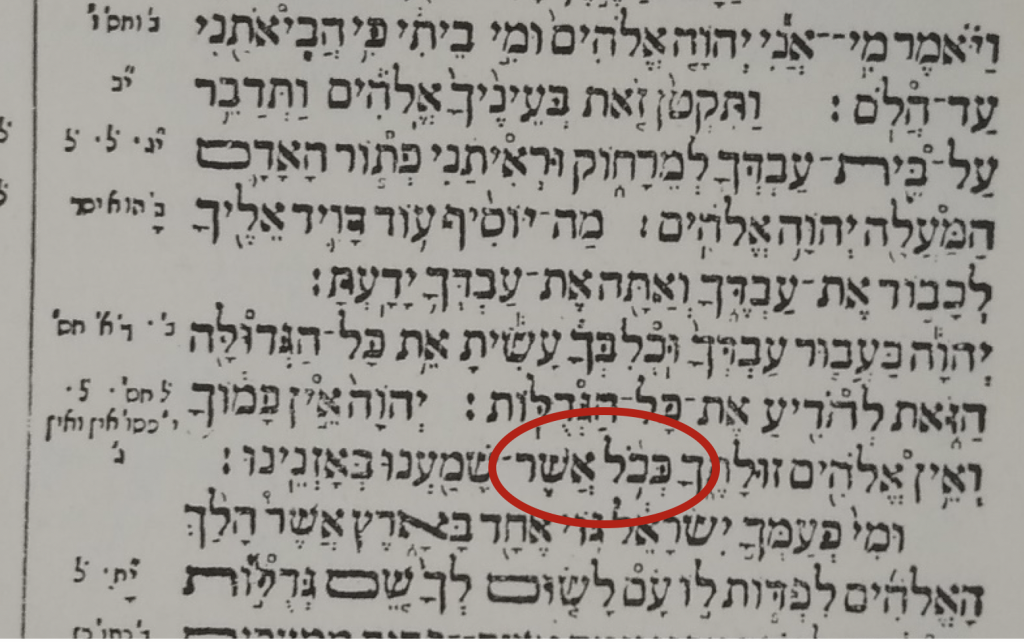

Okay, I know what you are thinking; maybe the text in the Leningrad Codex was incorrect (and the Karaites had it right all along). To examine this potential, let’s look at the evidence. Here is the masora gedola of the Leningrad Codex.

The Masora Gedola of the Leningrad clearly says that it is “bekhol” in chronicles. Click image to enlarge.

The masora gedola are masoretic notes by scribes and they provide information about all sorts of nuanced items. Here, the masora gedola clearly says that the word should be “kekhol” in Samuel, and “bekhol” in Chronicles (while discussing other differences between the verses). Meaning, that the mesora gedola tells us that the Karaites have the wrong word printed in their siddur.

This should resolve the debate – except for one small problem. The Leningrad Codex doesn’t read “bekhol” in Chronicles and “kekhol” in Samuel – as noted above, it reads “bekhol” in both. This doesn’t cause too much heartache here, because I am trying to prove what it says in Chronicles (not Samuel), and the masoretic note and text in the Leningrad Codex indicate that the word in Chronicles is bekhol.[2]

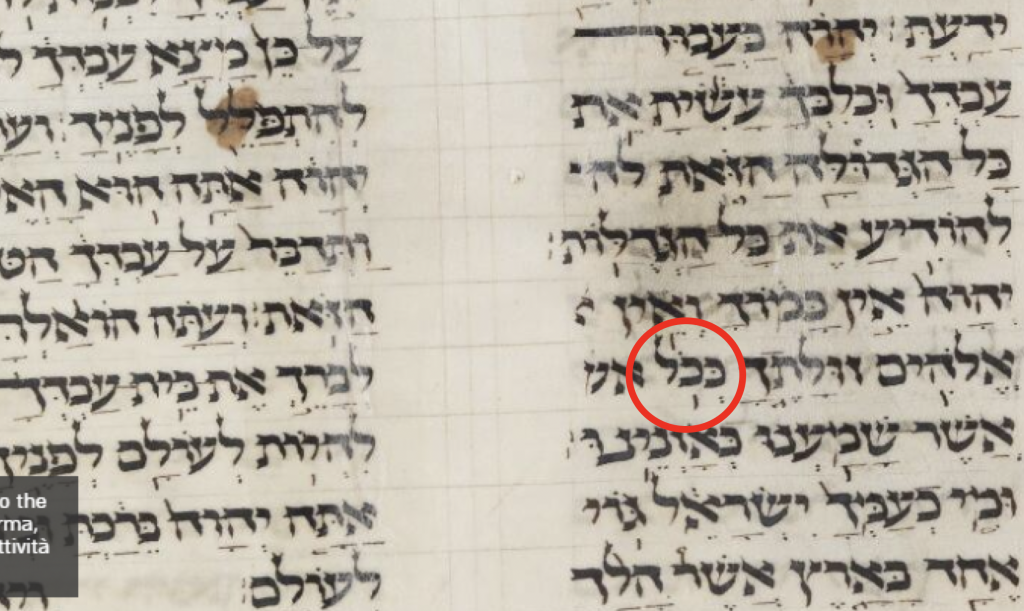

Examining the Evidence for Bekhol: The Aleppo Codex on 1 Chronicles 17:20

I know in theory, I should have started with the Aleppo Codex, given the esteem with which Karaites (and the Jewish and academic worlds) hold the work. The reason I didn’t is because at lease one famous researcher Rav Breuer believed that the text of the Aleppo Codex was indecipherable on this verse. (More on that below.)

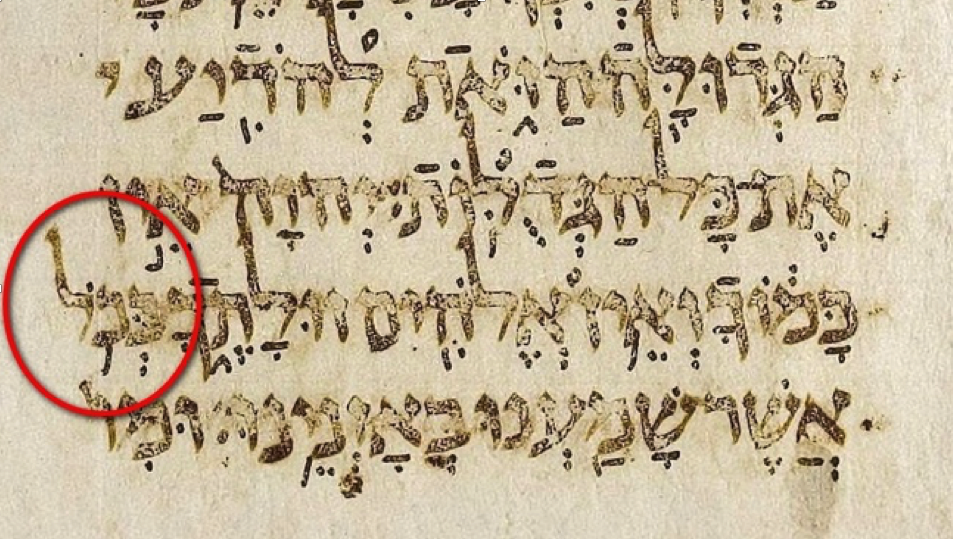

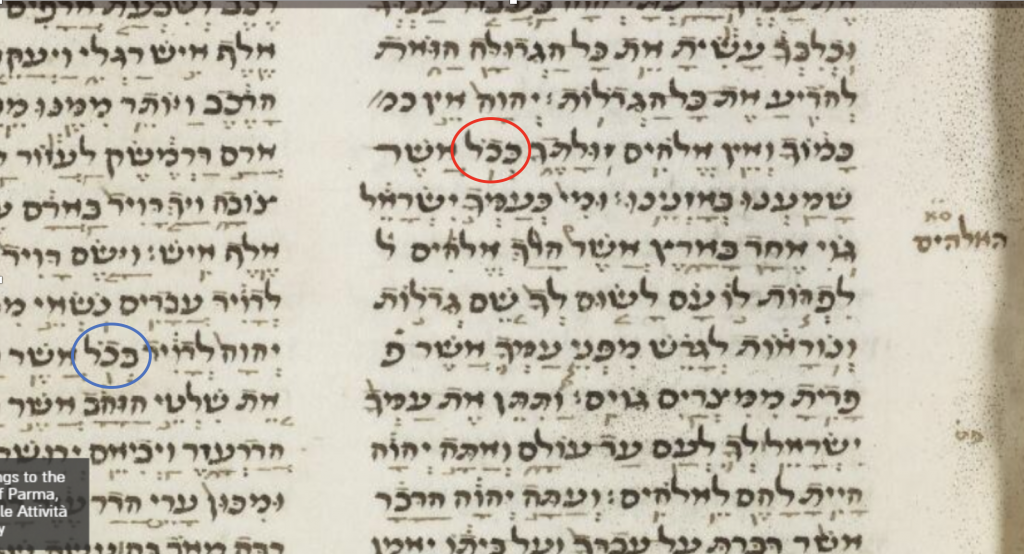

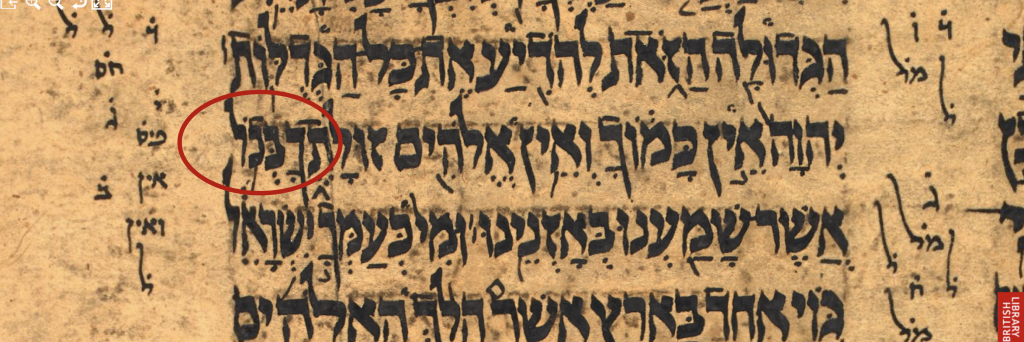

Here is what is in the Aleppo Codex for 1 Chronicles 17:20.

And here is a close-up of the exact word in question in 1 Chronicles 17:20.

I asked a professor whom I believe to be among the foremost authorities (if not the foremost authority) on these matters. Despite Rav Breuer’s uncertainty (described below) this professor states unequivocally that the Aleppo Codex reads bekhol. He says that the stains surrounding the letter are not an indication of an erasure or any change from one letter to another.

My own eyes tell me that he is right: it clearly, without a doubt reads bekhol, but feel free to reach your own conclusion.

Thus far, I hope I have demonstrated that the Karaite printing of kekhol

- is at odds with the Masora Gedola of the Leningrad Codex;

- is not consistent with the appearance of “bekhol” in the Leningrad Codex on 1 Chronicles 17:20

- is not consistent with the appearance of the Aleppo Codex, as interpreted by a foremost expert.

Examining the Evidence for Bekhol: Rav Breuer’s Red Book on 1 Chronicles 17:20

As I’ve noted, I think that it a high resolution photo of the Aleppo shows that the word is bekhol not kekhol. But Rav Breuer believed it was unclear when he investigated this issue very carefully his book נוסח המקרא בכתר ירושלים (The Biblical Text in the Jerusalem Crown Edition and its Sources in the Masora and Manuscripts, Jerusalem 2003). In this book, affectionately known as “the red book” because of its red cloth binding, Breuer shows how he built the text of Tanakh in his famous editions. He goes through all the words about which he found disagreements, and shows, in each case, what the various manuscripts read.

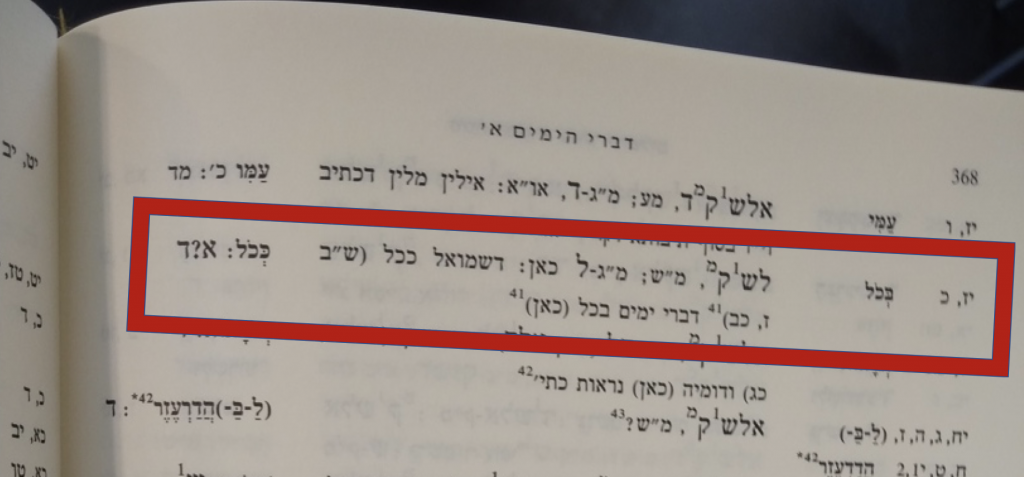

He determines that the word should be bekhol and here is what he puts in his book on the matter:

Here is how to understand his note:

- The far-right column lists the verse in question:

1 Chr 17:20

- Then, moving one column to the left, he lists the word as he has printed it in his editions:

bekhol

- Then he lists the support for his conclusion in the center section:

Leningrad, Sassoon 1053, Cambridge 1753, Minḥath Shai [by Yedidya Shelomo Raphael Norzi, 16th century]; Masorah Gedolah of Leningrad 1 Chr 17:20 [reads] thus: “of Samuel kekhol” ([referring to] 2 Sam 7:22) [but] Chronicles bekhol ([as we have printed] here).

- Finally, in the far-left column he lists other potential readings and their support:

kekhol: Aleppo Codex(?), Bomberg 1524 edition

At this point, it is imperative to observe two things:

First – Rav Breuer includes a question mark for the Aleppo Codex (represented by the Aleph), an image of which we have included above, because he is not entirely sure how to read it. I’ve noted above that others (including me) believe it is conclusively bekhol.

Second – Rav Breuer relies on the 1524 Venice Bomberg printing (represented by the letter Dalet, for the Hebrew word defus, printing) an image of which we shall include below. Although Breuer trusted this printing enough to use it as one of his sources for constructing his text, other scholars have noted that it is problematic, for reasons detailed in this footnote. [3] Note that already Yedidya Shelomo Refa’el of Norzi (1560-1626), in his work Minḥath Shai, noted and corrected thousands of errors that appear in the Venice printing. [4]

Thus far, I hope I have demonstrated that the Karaite printing of kekhol

- is at odds with the Masora Gedola of the Leningrad Codex;

- is not consistent with the appearance of “bekhol” in the Leningrad Codex on 1 Chronicles 17:20

- is not consistent with the appearance of the Aleppo Codex, as interpreted by a foremost expert

- is not supported by the following manuscripts and editions: Sassoon 1053 (image below) Cambridge 1753 (image below) or Minḥath Shai (image below);

- is supported by the 1524 Venice Bomberg printing (image below), but there are scholarly questions about the printing – even from close after the printing was made (as noted in Minḥath Shai).

Examining the Evidence for Kekhol: “Later” European Manuscripts on 1 Chronicles 17:20

When I reached out to the professor who is among the leaders in this area, I asked him directly whether he was aware of any early masoretic manuscripts that read kechol as is printed in the Karaite siddur. He responded that we could of course check the Geniza project to see if early manuscripts read the way the Karaites print it in their siddur. He added, though, that when we consider all of the important evidence Aleppo, Leningrad, Sassoon and Cambridge, we have strong and reliable evidence that bekhol is correct [and the Karaite siddur is incorrect], “even if we find one or two [manuscripts] that read kekhol.”

He is of course, correct. For almost any other phenomenon, we’d accept Aleppo and Leningrad as decisive (and when you combine it with the others, we should sleep well at night). But if anyone has proof that other early Tiberian masoretic manuscripts read kekhol, I would welcome it with open arms.

There are manuscripts that *do* say kekhol, but as far as I’ve been provided – they are from European sources that are a bit “later”.

—

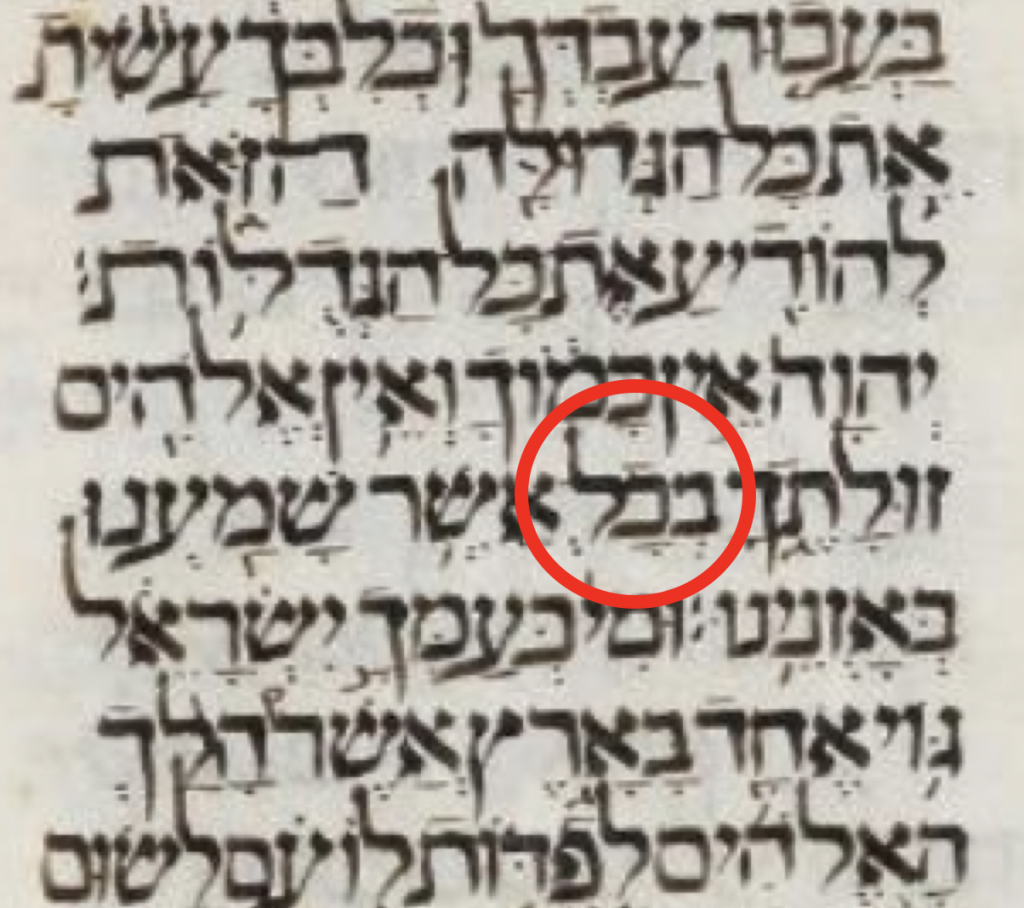

For example, this Manuscript Parma Palatina 3189, from fourteenth-century Archiac, France, (Note the Kafs and Bets look very similar, so it took me a while to conclude it indeed said kekhol.)

—

As another example, is a 15th-century European manuscript that has kekhol. Parma-Palatina 2515. Written in Civitanova Marche in 1425. (Because of the similarity of the Kafs and Bets I highlighted in red for you our word in question and in blue for you an instance of bekhol, so you can judge for yourself.)

To be clear, there were others from Europe that read “bekhol”, such as this one from 1473 (Parma-Palatina 2809).

So How Did this the Karaite Siddur Get it ‘Wrong’ – A Theory:

One of the persons I consulted on this suggested a rather simple solution about how the word “kekhol” got entrenched in the Karaite siddur.

Vindication for the Tiberian Masoretic Tradition

In all of this, one of my friends reminded me not to lose sight of the most important aspect: the precision and care of the Tiberian Masoretic scribal endeavor.

When the early masoretes were proofreading their manuscripts, they noticed that they inherited two separate traditions – one that says “bekhol” in 1 Chronicles 17:20, and another that says “kekhol” in 2 Samuel 7:22. The Masora of the Leningrad Codex notes that these two verses are very similar so it provides very clear instructions to the scribes to make sure they got it right. (Even with this note, they got it “right” in Chronicles and “wrong” in Samuel!)

But a problem remains in that we don’t know what David actually said in his prayer?! Did he “kekhol” (as reported in Samuel) or “bekhol” (as reported in Chronicles)?

The difference in meaning between the two words is virtually non-existent in Hebrew and virtually impossible to represent in English. [Editor’s Note: I added this previous line in response to a question in the comments.]

The Masoretic Scribes were okay with this inconsistency and they did not try to harmonize the two verses. And it is only because they were so precise in carrying out their mission that we are able to even “rely” on their work. Had they simply harmonized readings left and right, we would never know what to make of the text.

Truth be told, I had never really thought of – and certainly never appreciated – the masoretic precision until it came time to gathering convincing evidence that my siddur has a beautiful ‘mistake’.

Reader Poll:

So, now that you have all the evidence I have set forth above and below, what do you think?

* * *

Below, I provide the additional sources mentioned by Rav Breuer. The only one that shows “kekhol” in Chronicles is the Venice Bomberg Edition.

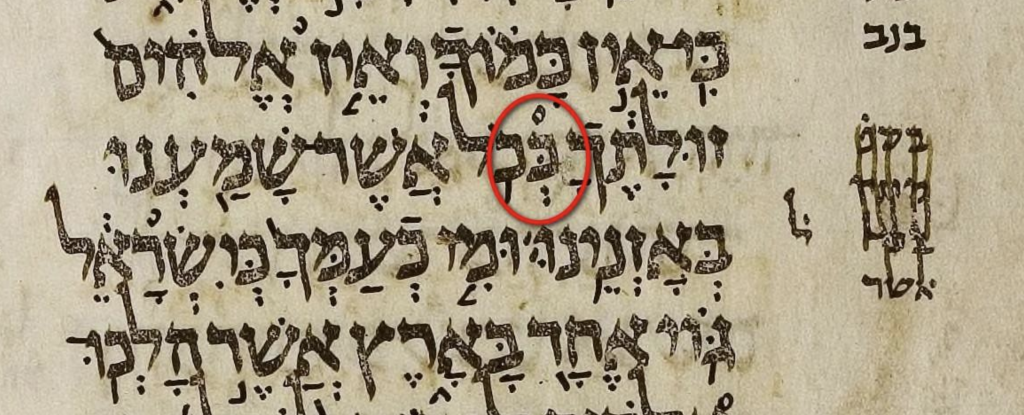

Sassoon 1053 – 10th century – bekhol

—

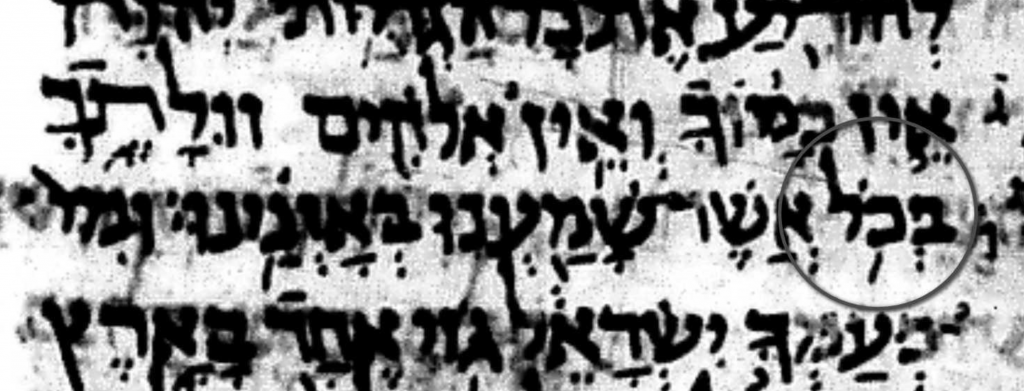

MS Cambridge Add. 1753 – bekhol: This manuscript is from the 16th century, which is late. However, it is considered one of the closest manuscripts to the Aleppo Codex and (according to a friend) may have been proofread using the Aleppo Codex itself.

—

1524 Venice Bomberg printing of the Tanakh (page 74) – kechol:

* * *

In addition to the manuscripts referenced by Breuer in the Chronicles discussion, we can show another important manuscript, British Library Or. 2375; it, too, reads bekhol.

This manuscript is important because Breuer himself used it to resolve issues where his main sources were deficient. It is also interesting from a Karaite perspective. This manuscript is a 15th-century Yemenite manuscript; incidentally, the manuscript also contains in it a portion of the work Hidaayat Al-qaari, by the Karaite Abu ‘l-Faraj Harun, about masoretic pronunciation.

* * *

And here is the Aleppo Codex on 2 Samuel 7:22 – if you look closely it appears that the scribe who wrote the consonants initially wrote “bekhol”. But it also appears that someone (perhaps Aaron ben Asher, or perhaps the original scribe) corrected it to “kekhol”.

* * *

[1] I must immediately acknowledge the invaluable assistance of Gabriel Wasserman and Nehemia Gordon, both of whom provided copious sources and images and worded/translated some of the academic notes in this article. They provided their notes to me separately and have given me permission to weave them into this article.

[2] This internal inconsistency has been well-observed, for example, Professor Dotan writes:

סתירה לפנים כה”י, שכן בו בשמואל: “בכל”, כנוסח שבדה”י. גרסת “ככל” מצויה אצל א ד, והיא מתאימה להערת מס”ג זו

“Internal contradiction in the [Leningrad] manuscript, because in Samuel it has “Bekhol”, the same as in Chronicles. The version Kechol [in Samuel] is found in Aleppo and the Second Rabbinic Bible (1524-1525) and fits this Masorah Gedolah note.”

Masora of Codex Leningrad (B19a) as arranged, deciphered, and annotated by Prof. Aron Dotan with the assistance of Nurit Reich, Tel Aviv University, 2014; Accordance edition hypertexted and formatted by OakTree Software, Inc. Version 5.0.

[3] Menachem Cohen, in his introductory essay to the Mikra’ot Gedolot ‘Haketer’ series (printed at the end of the Joshua-Judges volume, Bar-Ilan University, 1992) has a long description of this Venice printing of the Tanakh (pp. 1*-42*). He includes a section explaining the drawbacks of this edition: (a) the editor in Venice had access only to late Ashkenazic manuscripts of Tanakh, not early Tiberian ones; (b) the edition was put out in too short a period of time to allow Jacob ben Adoniah to make adequate textual decision (pp. 9*-10*). Cohen then proceeds to show all sorts of problems with the text. Later on (pp. 54* ff.), he notes that Mordecai Breuer built his Tanakh text from several main early manuscripts, plus the Venice printing; he writes: “Rabbi Breuer’s great success in using his algorithm of majority [that is, choosing the text that appeared in the majority of his sources] was due to the fact that most of his manuscripts indeed were at the top of the ladder of accuracy; only his choice to use also [Jacob] Ben-Ḥayyim’s edition ruined the algorithm a bit. We can see just how much [Breuer’s] results were due to chance from the fact that if he had included even one more manuscript on the [low] level of accuracy of the Ben-Ḥayyim edition, the results would have been very different.

[4] ככל אשר שמענו. בספרים כתובי יד מדוייקים בבי”ת.

Kekhol asher shama‘nu. In accurate manuscript books, it is with a beth.

One might find it strange that Rav Breuer used the Bomber edition, when he also had access to Minḥath Shai, which correct numerous Bomber mistakes. The reason is that he viewed them as separate sources and wanted to preserve their separateness in the event that Minḥath Shai got something wrong that Bomberg got right,

The fact that the word was Bekhol before someone changed it to Kekhol does not make it authentic. Without knowing who or when and why it was changed does not give it legitimate status.

The proof exists on the side of Bekhol without any question, even though the word is smeared in the Allepo Codex. I’m sure the word can be authenticated with modern technologies and be bullet proof.

Not only is the Bayt letter’s righthand tail scratched out in the Aleppo Codex at Shemu’el Bayt 7:22, but it appears that the Masora Qeṭana on the righthand margin, that apparently indicates the word should read “BeKhol”, was crossed out…

You did not explain what, if any, difference in meaning it would make if the word is actually “kekhol”.

I added a line explaining that there is no real difference.

I have checked what happens in the “Jerusalem Crown” (“the Bibileof the Hebrew University of Jerusalem”) edition, which is probably the closest to the Allepo Codex among all printed editions (though to some extent also on related MSS). It has the “BeKhol” reading in both places.

Hello, does anyone know if there is an email to the blog?

Thank you,

Matt

Shawn@abluethread.com

wow, shawn, well done!

without dealing with the development of the karaite siddur, which would require determining how the reading of ככל came into the text, here are my thoughts on the readings in 2 sam. 7:22 and 1 chron. 17:20:

our oldest hebrew manuscript for 2 samuel is from the dead sea scrolls (4Q51 sama), which reads בכל with a bet, not ככל with a kaf; 1 chron. is non-extant in the corpus. from an early hebrew vorlage, the greek from the septuagint also reads ἐν πᾶσιν | בכל at 2 sam., but κατὰ πάντα | ככל at 1 chron. – the same reading found in the karaite siddur.

before the masoretes (and even among the masoretes), like other similar letters (e.g., yod-vav or dalet-resh), kaf-bet confusion was a very common scribal error in the hebrew bible – the obvious visual similarities created the possibility for confusion. subsequently, the scribal tradition of the masoretes codified the transmission of the text as it was received, with whatever imperfection existed. i think that whatever the transmitted text looked like, logic would dictate that the source for these synoptic texts among the histories must have shared the same reading.

so, while the leningrad codex reads בכל at both 2 sam. 7:22 and 1 chron. 17:20, i would argue the opposite. i would theorize that the reading originated as a phrase, כְּכֹל אֲשֶׁר-שָׁמַעְנוּ, which is also found in josh. 1:17 as κατὰ πάντα | ככל with a kaf. if that is the case, and these were rooted in the same phrase, then all source readings were probably ככל. that would be my vote, anyway. 🙂

I’m voting for “keep”, because a learner’s siddur should familiarize the “learner” with the text they are preparing to read, not teach them a text that represents what the siddur “ought” to say.

Pingback: Everyone's Butchering ibn Gabirol's Poem, and You Should Too - A Blue Thread