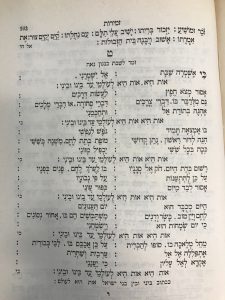

Ki Eshmera Shabbat, by R’ Abraham ibn Ezra, as printed in the Vilna Edition of the Karaite Prayer Book (Vol. IV)

Virtually, every Karaite respects Rabbi Abraham ibn Ezra. He lived in the 12th Century, and he is arguably the greatest of the classical Rabbanite peshatist (plain meaning) commentators. I have even quoted him in my talks. One of the reasons he is such a good peshatist is because he was combatting the then-thriving Karaite movement, which espoused peshat above all.

In addition to writing commentaries, ibn Ezra also penned numerous poems – the most famous of which is Ki Eshmera Shabbat. It is well known that the poem wound up in Karaite prayer books. It is less well-known that the Karaites modified the poem to remove anti-Karaite rhetoric. And it is even less well-known that the version that appears in Karaite prayer book still appears to have anti-Karaite polemics.

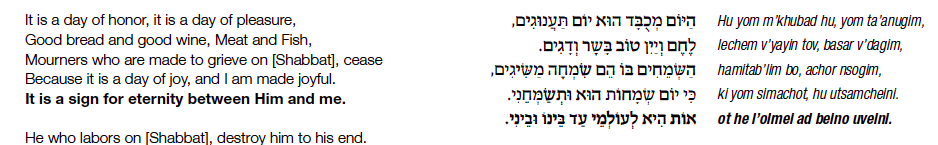

First, I should point out that there are different Rabbanite versions of Ki Eshmera Shabbat floating out there. These differences have actually caused confusion in the Rabbanite community when preparing song books. For example, I recently read that the “standard” version of Ki Eshmera Shabbat says thus in the fourth stanza:

The ones who rejoice on [Shabbat] will reach joy.

(Ha-semahim bo hem simhu masigim)

According to this same source, there is a Yemenite variation of this line, which reads as follows:

The ones who mourn on [Shabbat] are retrograde.

(Mitabelim hem bo ahor nesogim)

But you can see here, that at least one song book actually included the Hebrew from the “standard” version and the transliteration and translation of the “Yemenite” variation. See line three below.

Anyway, back to our story about how ibn Ezra trolled the Karaites: regardless of which version is the original, both of them can be understood as a direct polemic against the Karaites. The Karaite movement of 1,000 years ago was characterized (in large part) by the mourning over the destruction of Jerusalem. They even (it appears) felt that it was okay to mourn on Shabbat.

But because this line in ibn Ezra’s poem was understood as a polemic against the Karaites, the Karaite printing of Ki Eshmera Shabbat has something quite different (but is related in structure to the “Yemenite” version):

The ones who have intercourse on [Shabbat] are retrograde.

(Mishtameshim hem bo ahor nesogim)

The Karaite version is a polemic against the Rabbanites, who believe that sex on Shabbat is a double mitzvah. The historical Karaites believed that sex on Shabbat was an act of melacha (work). This is also (as far as I am aware) the majority opinion of observant persons of historical Karaite extraction today. There is a fascinating article about whether sex on Shabbat was always a double-mitzvah, posted at TheTorah.com.

Eli Shemuel (remember that guy?!) was the one who told me about ibn Ezra’s polemic against the Karaites (and the Karaite response) years ago. I also shared this observation with another young Karaite in the U.S.

Just last week, as I was reading more about this very topic, this young Karaite told me that he discussed the polemic with his mother and his mother reviewed the poem and noticed something interesting. The third stanza also seems like it is a polemic against the Karaites of ibn Ezra’s day – and this was something the Karaites did not change in their printings.

The third stanza reads (in relevant part):

Therefore, to make a fast on [Shabbat] is forbidden, in accordance with His wise men.

Only on the day of atonement do I fast.

(Al ken, lehit’anot al pi nevonav

Asur levad miYom Kipur avoni)

She was right; this does appear to be a jab at the same early Karaites who held it was okay to fast on Shabbat. Interestingly, the mourning part of this line would have been consistent with the views of later Karaite, who would have had no reason to change it to reflect their current mores. (To be clear, while I prefer to be joyous every day of the week, I see no religious reason why people cannot fast or mourn on Shabbat.)

But she also pointed out that the reason given for why it is forbidden to fast on Shabbat also seems polemical. The reason given is *not* that the text of the Torah forbids it; the reason given is that God’s wise men said so. Presumably, these wise men are the Rabbanite sages.

This got me wondering whether the entire poem is a polemic against the Karaites. So I reviewed the version of Ki Eshmera Shabbat that appears in Karaite prayer books, and there is at least one other sectarian difference between the Karaite printing and the Rabbanite printing.

In the fifth and final stanza, ibn Ezra’s text (as I have seen it in various rabbinic sources) reads:

I will pray to God in the evening and in the morning

the additional [prayer] and also the afternoon prayer, He will answer me.

(Etpalela el El aravit v’shacharit

Musaf vegam minha hu ya’aneni)

The version of the prayer that appears in the Karaite prayer book reads:

I will pray to God in the evening and in the morning

I will call out to the Most High God, that He will answer me

(Etpalela el El aravit v’shacharit

Ekra le’El Elyon ki ya’aneni)

The Karaite rendition of this line reflects our belief that there is no minha prayer in our daily tradition. Whether or not the removal of the reference to a musaf service was for poetic or Halakhic reasons requires more research. I don’t know whether ibn Ezra’s original qualifies as a polemic. Indeed, not every description of a sectarian difference is a polemic. But in the context of the rest of the poem, it just might be.

Don’t get me wrong, Ki Eshmera Shabbat is one of the best songs there is. I just can’t sing it anymore. To be honest, I have no problem with Karaites reading poems by Rabbanites. I have no problem with Rabbanites reading poems by Karaites. Good poetry should be embraced and studied. I do get concerned when a minority movement (such as the Karaites) tries to kasher a poem that contains sectarian differences (likely) meant to degrade the minority.

This discovery has prompted me to work with the KJA to produce a booklet of (mostly) Karaite appropriate Shabbat songs.

Dear Shawn:

Congratulations on the extremely impressive research on the Ibn Ezra poem. I write to highlight two points.

1. Not all historical Karaites prohibited sexual intercourse on the Shabbat:

Professor Fred Astren’s Book on “Karaite Judaism and Historical Understanding” page 95 writes of the first Jew reported to have used the term Karaite, Benjamin ben Moses Nahawendi that:

“Benjamin is closer to Rabbanism in his halakhah than Anan. He is credited with the anti-tradition statement: “Do not take lesson from his sayings,” referring to himself. (fn. In the commentary on Daniel 11:36, cited both in Jacob Mann, “Early Karaite Bible Commentaries,” esp. 519, and Ankori, Karaites in Byzantium, 211, n.14.) Whereas Anan prohibited using the scalpel for circumcision, Benjamin requires it. Whereas Anan’s self abnegatory aspect lead to prohibiting sex on the Sabbath, Benjamin permits it….”

Secondly, I believe that one of the ‘wise men’ who would frown upon fasting on the Shabbat is the prophet Yeshayahu who said: אִם-תָּשִׁיב מִשַּׁבָּת רַגְלֶךָ, עֲשׂוֹת חֲפָצֶךָ בְּיוֹם קָדְשִׁי; וְקָרָאתָ לַשַּׁבָּת עֹנֶג, לִקְדוֹשׁ יְהוָה מְכֻבָּד, וְכִבַּדְתּוֹ מֵעֲשׂוֹת דְּרָכֶיךָ, מִמְּצוֹא חֶפְצְךָ וְדַבֵּר דָּבָר. (Is. 58:13) The use of the term ‘Oneg’ is never used in association with a fast.

Shalom Eliezer,

It is not really a fair comparison to take a random word “oneg” and see whether it appears in relation to another random word “fast.”

But the first part of the sentence you quote says, “if you refrain from trampling the sabbath to do your own desires on my holy day , but you shall call the sabbath a delight.” The purpose of this verse is to say that the sabbath itself is a delight (by virtue of keeping the Sabbath). And you do not need your own affairs to make Shabbat a delight.

1. I am convinced, based on what we have gathered so far, that the word “Melakha” is a combination of work and task, which is why it is a difficult word to render in English.

2. Intercourse is a form of Melakha if the intention or/and outcome is the female’s insemination.

This instance of embracing a Rabbinic poem illustrates the grave danger in doing so; the Qaraite Ḥakhamim have failed to purge this poem of all the Rabbinic polemics or statements that seem suspicious as polemical statements. I would insist on having Qaraite poets exclusively creating Qaraite content. This failure sickens me and I solute your courage that led to your decision to desist from singing this poem. I can only hope that the hardcore traditional Qaraites in Israel e.g. Nati Morad match your level of courage and resolve.

Zvi – perhaps we should collaborate on a new Karaite Manual entitled “The Karaite Guide to Non-Melakha Intercouse”

I write separately to address the issue of fasting on Shabbat. It would appear that King David fasted on the Shabbat to make penance to save the life of his child. See 2 Samuel 12: 14-22

Eli`ezer: I am uncertain as to whether you intended to be sarcastic ally deride my remark or you were merely joking, Either way, you studied in the same high school as my dad (and aunt) and he is about 5 years your senior; you may even know him (if you are interested in additional details, shoot me a private message).

Please excuse the horrific typos.

Dear Zvi: thank you so very much for bringing that to my attention. You have my email…I’d love to catch up……

And no, it wasn’t sarcastic at all…(well writing the Manual might have been)….but the idea of non-melakha sexual intercourse is an important concept.

Are you aware that fasting on the Sabbath was also practiced by Abraham Maimonides? He felt that the term oneg is subjective, whereas others experienced an absence of pleasure when fasting he (Abraham) in fact derived pleasure from it.

Very interesting. Citation please?

With respect to kindling a flame on the Shabbat the Torah both commands the kindling of flame on the Sabbath and also prohibits it. These time, place and manner provisions are not in conflict with each other.

Permission; Bemidbar 28;9-10 [burnt offering of two rams on Yom Shabbat]; Shemot 27:20-21 [light the Temple Menorah daily including on Shabbat]

Prohibitions: Shemot 35;4 “Ye shall kindle no fire throughout your settlements (also translated as ‘habitations’) upon the sabbath day.’

The Torah prohibits a fire one’s settlements or habitations but permits it within the Holy Temple. The question is what did the ancient Israelis hearing these verses believe ‘mishvoteychem’ – i.e. habitations believe it extended to?

In my first trip to the Anan ben David Synagogue in the Old City with now Chief Rabbi Moshe Yosef Firrouz on my immediate right and a Karaite Hakham on my left, on a Friday Evening Shabbat service, I saw the Kohanim light an oil lamp chandelier before the services began. The Synagogue also has fluorescent lighting. Clearly the Karaite Kohanim in the Anan ben David Synagogue did not believe they were standing within a ‘mishvoteychem” .

On the issue of fire on Shabbat, scholar Phillip Segal has written in;

The Emergence of Contemporary Judasim, Volume Two: Survey of Judaism from the 7th to the 17th Centuries, the following;

“The use of fire on the Sabbath may not have been of great moment in the Middle East. But it was of immese consequence in the frigid weather of Troki, Lithuania, near Vilna, whither Karaites seem to have emigrated during the thirteenth century. People had to keep themselves warm or endanger their health. Consequently we find that by the end of the fifteenth century there had been an unaccustomed evolution in Karaism. People were using fire on Sabbath to heat their homes. It was vigorously opposed by some scholars and resolutions were passed in assemblies to prohibit it. but the will of the people had sway in Karaism as it often has in rabbinic Judaism. Thus while a letter of 1483 registers the attempt to permit this, the writer is aghast that anyone would violate the Sabbath. And yet centuries later as documents of the seventeenth century show, they were still enjoining it in public resolutions which means people were using fire to heat their furnaces or stoves (fn 31) Meanwhile also the communities of Constantinople and Adrianople had adopted the use of Sabbath candles during the fifteenth century, reversing a historic Karaite halakha. There were differences of opinion on this, and some who advocated the innovation as bringing cheer to the home continued to oppose heating homes as too wide a departure from tradition. But when all this is said and done, the custom of Sabbath candles moved north from Turkey, as undoubtedly the heating of homes and food moved south. Even where communities continued to object to Sabbath candles during the fifteenth century, reversing a historic Karaite halakha. there were differences of opinion on this, and some who advocated the innovation as bringing cheer to the home continued to oppose heating homes as too wide a departure from tradition. But when all is said and done, the custom of sabbath candles moved north from Turkey, as undoubtedly the heating of homes and food moved south. Even where communities continued to object to Sabbath candle-lighting at home, as in Egypt, Syria and Palestine, the individualism of Karaism asserting itself, they often kindled lights in the synagogues. (Fn.32)

This new attitude on the part of Karaites to lighting fires on the Sabbath was a far cry from the position taken by Judah Hadassi, twelfth century author of a work called Eshkol ha’Kofer, a severely polemical anti-rabbinic volume. In that book Hadassi argued that it is not even appropriate to kindle a fire on the Sabbath for the benefit of a childbearing women even if her life be jeoparized. He argued from the statistical evidence that ‘so many women in childbed without a candle or fire who notwithstanding labor pains were saved by the grace of God…” Even earlier the thrust of the rabbinic leaders against this germinating insensitivity was to further elaborate ceremonial in order to make a contrary statement.

A special benediction was required for Sabbath candles by the post-talmudic scholars and I feel certain this was virtually an anti-Karaite innovation. Since the Karaites were opposed to the kindling of lights altogether and called it a descration of the Sabbath, the Rabbanites went to the opposite extreme and sanctified it with a berakha. They were asserting that not only may a Jew kindle this aid to comfort, but must affirm it to be part of God’s gracious hallowing of life. (fn 33).

After the earlier generations of great hostility the two major segments of Judaism began to have reasonable relationships as can be seen from the documents available to us. Marriage between certainly indicates something. In addition to that Karaites began to study rabbinic literature and not only to obtain grist for their mills. Thus a major fourteenth century Karaite scholar, Aaron ben Elijah, who covers the entire range of Karaite religious thought, including halakha and philosophy, was also well-read in all the major rabbinic writings from the Talmud through Saadiah to Maimonides. (fn.34). In his halakhic work, Gan Eden, he portrays the Karaite festivals and provides a reasonable picture of precisely what Karaites observed.

Interesting that you bring that up. The mitswah concerning the shabbath lists several persons which are prohibited from mel’akhah on yom shabbath. The word mel’akhah was qualified in this mitswah, and every other mistwah repeating it, by two verbs- ta’avodh and ‘asitha; this indicated that mel’akhah consisted of service [avodah] as well as that which was done [ma’aseh]. In those places where the Mishkan and its avodhah was mentioned, the word mel’akha was- for the most part- in construct with avodhah [melekheth ha’avodhah]. The Kohanim were always exempted from the prohibition of mel’akhah on the shabbath day; in the same way, they were prohibited from alcoholic beverages while they were in service, but the other Israelites were allowed to partake of it.

I have explained before, in other social media, that the commandment had nothing at all to do with kindling a fire, but with burning- this is the underlying meaning of ba’ar in every verb form with fire. The commandment lo tava’aru esh bekhol moshevotheykhem beyom haShabbath meant literally- you [plural] shall not burn a fire, in any of your habitations, on shabbath day… Although this was given when Moshe (AS) gathered the children of Israel together, the Kohanim were exempted from this prohibition- even though they were not specifically singled out in this place. If this were not the case, then all of the services of the Sanctuary [ אֶֽת־כָּל־מְלֶ֖אכֶת עֲבֹדַ֣ת הַקֹּ֑דֶשׁ] would cease on every Shabbath, but we know there were commandments to the contrary.

I am sure you did not mean to make this unqualified statement;

‘The Kohanim were always exempted from the prohibition of mel’akhah on the shabbath day’

If this were the case one could argue that a Kohen could conduct commercial transactions on the Sabbath, buy and sell stocks/bonds, etc., However, the Kohanim are subject to the same restrictions as all other Jews, but they were granted specific special exemptions to do acts within the Temple precinct which would otherwise be considered melakhah.

In a legal sense, lawyers oftentimes are called upon to analyze statutes by determining a general statute’s application versus a specific statute. The common law courts have held that the specific overrules the general when its underlying facts apply. The Torah in that regard is no different.

Eliezer, there is no link to reply to your last post, so I will post here. I apologize in advance for any confusion it may cause in the thread.

Mel’akha was never qualified in the mitswah [it never stated what mel’akha specifically was] except by the two verbs I mentioned. The Kohanim are exempted from mela’kha as they are able to serve and to do mel’akhah on the Shabbath- without any other qualification mentioned in Torah. There was a case where a man was caught gathering wood on the Shabbath and was executed for this act; the Kohanim gather wood and place it on the altars to burn fires- which was also prohibited to other Israelites on Shabbath. Personally, I would hold that they were only exempted from this mitswah while in service- as I previously mentioned; when, however, they were not serving in the capacity as Kohen in the Mishkan, they must observe Shabbath like we are- they are also allowed to partake of alcohol when not in service of their priestly duties. That is simply my opinion- which really doesn’t count for anything.

What Torah passage offers a general exemption from the Shabbat to the Kohanim?

Eliezer,

The mitswah qualified mel’akha as that which one served at or which one did-

שֵׁ֤֣שֶׁת יָמִ֣ים֙ תַּֽעֲבֹ֔ד֮ וְעָשִׂ֖֣יתָ כָּל־מְלַאכְתֶּֽךָ֒׃

Six days you shall serve and you shall do all your mel’akhah

וְיֹ֙ום֙ הַשְּׁבִיעִ֔֜י שַׁבָּ֖֣ת׀ לַיהוָ֣ה אֱלֹהֶ֑֗יךָ לֹֽ֣א־תַעֲשֶׂ֣֨ה כָל־מְלָאכָ֡֜ה

But on the seventh day [is] a ceasing for YHWH your Deity; you shall not do any mel’akhah.

The priestly duties in the Mishkahn are defined as service [avodhah] and as melakhah. There are also places where the two terms are combined in a construct form [melekheth ha’avodah]. Although this is a construct, it may also be understood as a definite clause- this is like many other constructs, ie. yam haShevi’i [ the seventh day].

Speaking of the Lewi’im [the Nethanim] who were given to the Kohanim to serve them in the Mishkan, the Torah stated:

וְשָׁמְר֣וּ אֶת־מִשְׁמַרְתֹּ֗ו וְאֶת־מִשְׁמֶ֙רֶת֙ כָּל־הָ֣עֵדָ֔ה לִפְנֵ֖י אֹ֣הֶל מֹועֵ֑ד לַעֲבֹ֖ד אֶת־עֲבֹדַ֥ת הַמִּשְׁכָּֽן׃

In their duties, they were said to serve the service of the Mishkan- according to Divrei HaYamim Alef 28, 28-32, we know that they served- along with the Kohanim- every Shabbath. By the simple act of doing their service on Shabbath [וּמַֽעֲשֵׂ֔ה עֲבֹדַ֖ת בֵּ֥ית הָאֱלֹהִֽים׃], they are in violation of the rigid clause of Shabbath

שֵׁ֤֣שֶׁת יָמִ֣ים֙ תַּֽעֲבֹ֔ד֮ וְעָשִׂ֖֣יתָ כָּל־מְלַאכְתֶּֽךָ֒׃

וְיֹ֙ום֙ הַשְּׁבִיעִ֔֜י שַׁבָּ֖֣ת׀ לַיהוָ֣ה אֱלֹהֶ֑֗יךָ לֹֽ֣א־תַעֲשֶׂ֣֨ה כָל־מְלָאכָ֡֜ה

Not only were the Kohanim exempted from the prohibition of serving and doing mela’khah, but the Lwi’im Nethanim were as well.

Correction: yam haShevi’i [ the seventh day]. Should read yom haShevi’i [ the seventh day].

Again, I must point out my earlier opinion that this exemption extended only to their service as Kohanim. When they were not in the office of Kohen, they were under the mitswah of keeping Shabbath as any other Israelite.

Did you mean the Abraham Maimonides who was A Jewish Sufi?

See, http://www.tomblock.com/shalom_jewishsufi.

If so, why should I care?

Shalom

As a displaced Karaite in a very strange land with no personal contact it is challenging to live a Torah life but nevertheless this is my first thought

As I read this, my mind thought what is the difference in the Rabbanites view and the Christian view,on adding would YAH say it is OK for my confused people to add but not for the Christian’s to add would he play favourites

My answer was (no) Before Solomon death there were only two types of people the righteous & the sinner’s you walked in Torah or you did not degrees would not have been an issue so you would be righteous or the Sinner. why would one look at anything outside of HIS way no matter who they are as being OK ! as for the sex component where is it written that sex is work ? Unless that was your job tongue in cheek .

When my wife and I converted in 07 I had to present an essay on the part of Torah that was meaningful to me.

I chose Duet4:2, for this I felt and still feel it is the most important commandment in all of the Torah it is how I am it is my guarantee of truth !

Where is it found in Torah is the

(Australian Karaite view)

We must not add in this or anything is my view how can a person know what is right in GOD’s eyes if there are unknown degrees this can not be so may YAH bless us all with his truth and only HIS truth which is only found in Torah not in any man’s view .

Shalom Kalev, the part about sex on shabbat was not tongue in cheek. The key is that not everything that is Melacha (“work”) is recorded as melacha. The idea is tha tmelacha was a word that the average Israelite knew – so it did not need to be defined in the text. Let me give you one example. From the Torah alone, we would not *know* that buying/selling on Shabbat is forbidden. But we see in the book of Nehemia that this was deemed forbidden? How did they know that? Was it because there was an Oral Law? No; it is because they knew what melacha was.

Thanks!

Ibn Ezra apparently was not all that he seemed. Many believe he used Karaite interpretation without credit of course.

http://hirhurim.blogspot.com/2008/03/ibn-ezra-and-karaites.html

Regardless of melachah, sex is an act which causes impurity. Shabbath is a period of sanctity and, like any other sacred object- time included, rules to sanctity applied. Since we are required to sanctify Shabbath, the rules of purity- should- apply. If we cannot approach that which is sacred in a state of impurity, shabbath- as a sacred day- deserves no less respect or treatment.

As in all my views where is it said in Torah that is my only view we can have our view but it would not be wise to add I would have thought at least that is and always be the Australian Karaite view

May YAH bless us all

Kalev

The children of Israel are instructed in Torah to “sanctify” themselves not just on the Shabbat, but during the entire week. Vayikra 11:44-45, which does not reference the sabbath, states:

44. For I am the LORD your God; sanctify yourselves therefore, and be ye holy; for I am holy; neither shall ye defile yourselves with any manner of swarming thing that moveth upon the earth. 45 For I am the LORD that brought you up out of the land of Egypt, to be your God; ye shall therefore be holy, for I am holy.

By this logic the Jewish people can never have sexual intercourse….yet our Torah made a promise to Abraham that “I will make your descendants multiply as the stars of heaven; (Beresheet 26:4).

So the question is whether someone who is a state of Tame (Impure) make the Shabbat unholy? Think about that for a second…. That would mean if I came into contact with a dead body thereby becoming Tame could I make the shabbat “unholy” for the entire Jewish people? Of course not. In fact the Torah tells us: “”you must warn the Israelites about their impurity, so that their impurity does not cause them to die if they defile the tabernacle that I have placed among them” (Lev. 15:31). If one is impure, whether or not on Shabbat, an observant Jew should scrupulously avoid attending a House of Worship.

The impurity laws were specifically in regard to contact with that which was deemed sacred- the Sanctuary and it precinct in particular. This was visited during the week as well as during shabbath- therefore religious duties are not considered among melachah. Shabbath, as well as other mo’adim are also sacred and should not be approached in a stated of impurity. During other non-sacred days, the Sanctuary and it’s precincts could be avoided, but not can avoid a sacred time. I agree that we may not always avoid becoming impure, but that does not lay aside the duty to approach the sacred as pure as is possible. We were warned specifically against profaning the Sanctuary and against the Shabbath.

Shalom.

Ich habe vor einiger Zeit einmal gelesen, dass das Wort “Shabbat” den Gedanken der Vervollständigung bzw. Vervollkommnung enthält.

Am Berg Sinai hat HASHEM gesagt:

“Ihr sollt heilig sein, denn Ich bin heilig.”

“A minority is always compelled to think.

That is the blessing of being in the minority.”

–Leo Baeck

I “get” knowing beautiful songs and letting them go because of having learned “too much” about the origins. I remember hundreds of songs I can no longer sing from “x-endom.”

The places where we are able to find common ground between Karaite & Rabinical Judaism, or places where we can muster the capacity to bend without breaking our own understanding of Torah may become strengths.

For me:

Does Torah command us (vitzivanu) to Kindle the Sabbath lights? No. It’s Rabinical instruction.

Is there a command in Torah to separate the Shabbat? Yes. We are told not to kindle on Shabbat.

Did YHWH extinguish the sun’s fire on Friday at sunset, or declare it good, and let it burn through sunrise & all day on Shabbat? We have a precedent set by the Creator to enjoy the “good” fire that is already kindled.

My understanding, at this point, is that I may light before sunset & enjoy what already does exist on Shabbat. We celebrate what we have already created during the week.

No, I don’t expect you to take my word as permission. Figuring it out for yourself and your family is your own responsibility.

The point is that the flexibility here allows fellowship by changing one word: “natanlanu” in place of “vitzivanu.”

Suddenly, Rabinical Judaism is my ally in making Shabbat special, building memories & connection. Yes, I want Karaite allies and tools and songs as well. If we want the next generation to survive as thinking, discerning, Torah – walking people, we must find the common ground within Torah where it may be found.

No, I don’t see the, “…My sons have defeated me!” line as binding me to finding truth in opposing views. That doesn’t mean that I must reject everything they taught. It’s ok, and even good, to build bridges where we are able.

For the moment, the songs we learned from Rabinical Judaism are the ones we sing when the rest of the world sings a different tune. Building bridges and walls can both be good. It’s also good to rest from both, and see the good in what already exists.

Yochanna wrote, “Did YHWH extinguish the sun’s fire on Friday at sunset, or declare it good, and let it burn through sunrise & all day on Shabbat? We have a precedent set by the Creator to enjoy the “good” fire that is already kindled.

My understanding, at this point, is that I may light before sunset & enjoy what already does exist on Shabbat. We celebrate what we have already created during the week.”

My reply:

The fallacy of this opinion lies in the Hebrew itself; the mitswah said nothing about kindling a fire, but about burning one. The Hebrew read

לֹא־תְבַעֲר֣וּ אֵ֔שׁ בְּכֹ֖ל מֹשְׁבֹֽתֵיכֶ֑ם בְּיֹ֖ום הַשַּׁבָּֽת׃

The verb which is- most often- translated “kindle” is vocalized by the Mosoretes as a pi’el; the pi’el is a causative as well as a verb which indicated the continuance of the root. Consider the following:

The verb LaMaD meant to learn, but the pi’el meant to teach- a causative of learning:

וְעַתָּ֣ה יִשְׂרָאֵ֗ל שְׁמַ֤ע אֶל־הַֽחֻקִּים֙ וְאֶל־הַמִּשְׁפָּטִ֔ים אֲשֶׁ֧ר אָֽנֹכִ֛י מְלַמֵּ֥ד אֶתְכֶ֖ם לַעֲשֹׂ֑ות לְמַ֣עַן תִּֽחְי֗וּ וּבָאתֶם֙ וִֽירִשְׁתֶּ֣ם אֶת־הָאָ֔רֶץ אֲשֶׁ֧ר יְהוָ֛ה אֱלֹהֵ֥י אֲבֹתֵיכֶ֖ם נֹתֵ֥ן לָכֶֽם׃

And now, O Israel, listen to the statutes and to the ordinances, which I am teaching [melammeidh- a pi’el participle] you, to do them; that ye may live, and go in and possess the land which the LORD, the God of your fathers, giveth you. Devarim 4,1

The verb HaYaH meant to live; the pi’el can mean to revive [return to life] or to extend one’s life or allow one to continue to live:

מְכַשֵּׁפָ֖ה לֹ֥א תְחַיֶּֽה׃

A witch you shall not allow to live [tehayyeh- pi’el imperfect 2nd]. Shemoth 22,17

יְהוָ֖ה מֵמִ֣ית וּמְחַיֶּ֑ה מֹורִ֥יד שְׁאֹ֖ול וַיָּֽעַל׃

YHWH causes death [hiphil participle] and returns to life [pi’el participle]; causing to descend [hiphil participle] to she’ol and causes to rise [hiphil imperfect 3rd]. Shemuel Alef 2,6

From this, we can learn that to continue a fire to burn [the meaning of the root ba’ar] as well as causing a fire to burn are both within the meaning of the pi’el verb used in Shemoth 35,3. Another thing to consider is the fact that it was the Masoretes who vocalized the Hebrew Text; the pi’el and hiphil imperfect 3rd can be written the exact same way; the Samaritans have this verb written in the hiphil- with the Yod and not written defectively. This, of course, is perfectly fine when considering the Text and the usage of the pi’el and hiphil verbal stems.

I hear and appreciate your well-thought-through discussion.

It may be that my western glasses interpret a verb as requiring action, which would no longer be mine to do once the fire is already lit.

It may also be that my very rustic livibg situation in the Frozen North also gives me something of a different perspective in that the absence of a previously-lit fire for 24 or so hours could mean freezing to death, literally.

I will think on what you have written here.

Inaction is also an action; das in the example above:

מְכַשֵּׁפָ֖ה לֹ֥א תְחַיֶּֽה׃

A witch you shall not allow to live [tehayyeh- pi’el imperfect 2nd]. Shemoth 22,17

allowing that which is prohibited to continue is also not allowed. Even though we don start a fire, and may not be the cause of it, to allow it to burn is also not allowed.

There may be exception in other places outside Israel, but I am not aware of such. We have, das part of our commandments,

לֹֽא־תִשְׁתַּֽחֲוֶ֥ה לָהֶ֖ם וְלֹ֣א תָֽעָבְדֵ֑ם כִּ֣י אָֽנֹכִ֞י יְהֹוָ֤ה אֱלֹהֶ֨יךָ֙ אֵ֣ל קַנָּ֔א פֹּ֠קֵ֠ד עֲוֺ֨ן אָבֹ֧ת עַל־בָּנִ֛ים עַל־שִׁלֵּשִׁ֥ים וְעַל־רִבֵּעִ֖ים לְשֹֽׂנְאָֽי׃

You shall not submit yourself [hitpael, a reflexive] to them, nor be made to serve [hophal, a causative passive] them; for I YHWH your God am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers upon the children to the third and fourth generation of them that hate me.

The first verb is reflexive- we chose to do so ourselves; the second verb is a causative passive- we are made to do it.

I, pesonally, would consider moving to a place in which it is more conducive to keeping Torah.

I hear your thoughts.

We have rarely been accused of inaction.

Just as I do not expect anyone to take our experiences as permission, I also do not jump because another human tells me I must.

We moved here recently under duress, but with forethought, considering the effects on future generations.

As I said, we will consider what you have written, but you are also human, interpreting Torah through your own lenses.

YHWH gave us land when we were slaves in the rental market, in an increasingly impossible economy.

He brought us out, to this parcel.

We have seen dozens of “minor” miracles here, allowing us to settle this land.

If YHWH should move us again, I pray that it be to Eretz Yisrael.

May He send the priest with urim and thumim to settle our questions in our days.

Meanwhile, we study and yes, act.

Yochanna replied ” I also do not jump because another human tells me I must.”

My response:

I was not telling you to jump- simply offering my opinion as to a situation in which possible violations of the sanctity of Shabbath occurred. I would, howbeit, like to address your statement.

The Kohen Gadol, in my opinion, the Judge of Devarim 17 [based upon several passages- the most important is the understanding provided by Yehezqel (AS) in 44,23-24], has the last say in matters of YHWH’s Torah- he, and the court of Kohanim, are human beings.

In addition to the court of Kohanim, there were local magistrates- the Hakhamim, who were appointed to judge the people at all times- only those matters which could not be settled among the local magistrates were sent to the High Court. These, as well, are also humans.

Although, technically, there might not be an active Kohen Gadol, there are the Hakhamim/Shofetim [the role of the shofetim was equated by the title Elohim when judging matters of Torah; see, for example, Shemoth 22,8 and Divrei HaYamim Beth 19,6] who may be appointed by the Israelites who judge matters; these are also humans. We are bound- according to the Torah- to obey these men. The only objection to this, that I know of, is when they command that which is obviously forbidden.

Since this is, after all, a Karaite blog, I will offer the 7th article of faith

ז׃ וּבִלְשֹׁון הָעִבְרִי נִתְנָה תוֹרַת הָאֱלֹהִים וְלָכֵן חוֹב לִלְמוֹד וְלַהֲגוֹת לְשׁוֹן הַתּוֹרָה וּבִאוּרָה

Zayin: And in the Hebrew Language in which the Torah of Elohim was given; therefore it is an obligation to learn and to study [pronounce. meditate and reflect upon] the language of the Torah and its exegesis.

If, however, one fails in this duty, or is not capable of fulfilling this requirement, it is better to ask and listen to those who have fulfilled this requirement and be chosen as Sages among the people.

I am currently looking to see if there may be other precedents in which a situation similar to yours might be addressed- it does not, so far, appear to be any. Nonetheless, I wish you all the best in finding a solution.

If you do find such a sage who has offered a judgment, I would be interested to see the sources. I thank you for your effort in looking.

Blessings.

The only one I have found- so far- is Eliyahu ben Moshe ben Menahem; he allowed the use of fires previously started during Shabbath. He was, however, heavily influenced by Rabbinic Judaism.

Even in the hard Russian winters, the Karaites there were reported to have dug holes and buried themselves during Shabbath. As an alternative, I would have used a yurt in the winter. Once sufficiently warmed, the inside would remain warm- as long as no one entered or left frequently to lose heat.

Russian winters are very comparable to here. Some days Siberia is colder. Some days we are.

We did use a yurt the first year, but it wasn’t warm enough past mid-November, and the water had to be kept outdoors, due to square footage limitations.

We are thankful for grain bins this year. They are much more tornado resistant, as well as warmer, now that they are (partially) insulated.

Yes, keeping the door shut does help retain heat. So does an airlock entry.

I do wonder whether burying & shivering may be more work than intended for the Day of Rest. Maybe a more generous understanding of the Author of Shabbat could lead to more respect between factions of Judaism who do, at their core, want to honor Torah as well as the Author. I see a potential path toward isolation from other Jews in condemning the traditions that families have used to make Shabbat special for thousands of years.

I also see potential for sharing of the Karaite traditions with Rabinical Jews, absent any perception of condemnation.

At its core, Karaite Judaism is all about personal responsibility to our Designer. That personal relationship is likely to become more educated, but not necessarily less individualized through broadened access to varying interpretations via technology. Future generations may need us to have opened doors of communication, as well as capacity for humility in judgment. They may have more difficult roads to walk than we have. I pray not. Whether they do or not, may they find Torah and those who honor it (to the best of their ability & understanding) a refuge, a haven, and a blessing. May the Author of Creation and of Torah have mercy on us all where we fail, and may we learn well before He must make this most generous of concessions:

Jeremiah 17:24-27

The gist of it:

Avoid carrying a burden on Shabbat, and David will have an heir on the throne again.

To the salesman, his wares are a burden. To the arthritic, walking may be a burden. To the dyspeptic, eating may be a burden. To me, being “a little chilly” is horribly painful, and a burden.

Maybe a little ambiguity is intentionally left in Torah so that we will argue and discourse and struggle with it, and learn to approach it with grace for those whose Breath of Life resides in a different organism?

Yohanna explained, “Avoid carrying a burden on Shabbat,”

I reply:

It is a bit more to it than simply carrying a burden on shabbath. The clause, in Hebrew, is:

לְבִלְתִּ֣י׀ הָבִ֣יא מַשָּׂ֗א בְּשַׁעֲרֵ֛י הָעִ֥יר הַזֹּ֖את בְּיֹ֣ום הַשַּׁבָּ֑ת

The first negating particle is lebilti- from beleth. It mean the non-existence of a thing- similar to the particle [אין] ain. The former is used- primarily- in the negation of infinitives while the latter is used- primarily- in the negation of nouns.

The infinitive used is [הביא]havi’ – a hiphil, or causative. The idea is that there should not exist any cause to bring in….

There should exist no cause to bring a burden into this city on the Shabbath day. Yirmiyahu (AS) lived prior to, during, and shortly after the fall of Jerusalem; this situation, unfortunately, was mirrored in the days of the return of the captives under Nehemyah (AS) [chapter 13].

It was not simply carrying a burden on shabbath as much as it was bringing merchandise into Jerusalem for sell and trade in shabbath.

Agreed.

Don’t profit by it; buying / selling. No burden of wanting, deciding, haggling, lugging home, etc. Just release. One-day shmitta.

Hunting for Eliyahu ben Moshe ben Menachem’s

“Mantle of Elijah”

Do you know where to find it?

I have it in Hebrew PDF- if you want it.

jlmetzsc@gmail.com

Thank you!

I just emailed.

🙂

Maybe check your spam folder?

I have already emailed it to you- the same day you emailed me.

Ok. I did check my spam folder.

Will look again.

Thank you.

Found it!

Todah Raba!

It seems that my comments are now being moderated; I have posted the same reply- concerning sexual relations on Shabbath- three separate times. The first was over a week ago- none, so far, have been made available.

Hi Jacob, your comments are not being moderated. I do not see any in the spam filter either. There are several of your comments on this thread already.

Thanks. Perhaps it was a glitch in the thread or, even more likely, I was not meant to publish that thought.

Shalom.

Danke. Habe gerade diese Seite entdeckt und bin begeistert über die Vielschichtigkeit dieses Textes, die für mich keinen Widerspruch ergibt.

Sondern seine tiefe Klarheit zum Ausdruck bringt.

Im ersten Moment scheinbar ein Widerspruch, aber wenn man innehält, eine Tiefe aufzeigt, die viele heute übersehen!