Breaking News: Earlier this morning, the Supreme Court of the State of Israel

Breaking News: Earlier this morning, the Supreme Court of the State of Israel

ruled in favor of the Karaites in a court case against the State’s religious authorities, who had tried to prevent Karaites from slaughtering in independent slaughterhouses that were under the Rabbanut’s supervision. I dedicate this post to everyone who worked so hard on that case.

* * * *

In the Rabbinic community, there are famous debates concerning the minhagim (and halakha) of Ashkenazi and Sefardi Jews. Everyone is familiar with the Passover/kitniyot debate. And historically it was the case that if you were from an Ashkenazi family, you followed your own minhag; and your Sefardi friends followed their own.

Geographic divisions like this, tend not to exist in the Karaite community. But historically there was one debate that divided the Karaites on theological lines, and caused a rift among geographical lines that somewhat reflects the Ashkenazi/Sefardi divide in the Rabbinic community.

First, I note that it does not really make sense to speak of “Ashkenazi” or “Sefardi” or “Mizrahi” Karaites in the cultural and halakhic sense. These terms generally (though not always) are used to denote the differences in customs among the Rabbinic community. But this is a topic for another day. . .

As a Karaite, I always thought that it was strange that Jewish law could vary on an issue such as the permissibility of certain foods based on where you were from. I would expect the law to vary based on which interpretation seems the most reasonable, regardless of geography. Of course, certain community norms may develop; but we must always make sure we are guided by the text as much as possible.

Back to our Karaite geographic dispute: it concerns the laws of shechita. No, it did not concern how to actually slaughter an animal; nor did it concern which types of animals may be slaughtered.

It concerned the belief system of the slaughterer.

Yes; there was a debate in the Karaite community about whether meat was fit for consumption based on the slaughterer’s theology. And we’re not talking about whether the slaughterer was an idolator or an apostate.

The Karaites who lived in Egypt, the Land of Israel, and Syria believed that an animal that was slaughtered received a form of compensation from God. It is almost certainly the case that the Rabbinic Sage Saadiah Gaon also held this view. The theory goes like this: because slaughter causes more pain than a natural death (in most instances), the animal must be compensated for this pain, and it is God that grants this compensation.

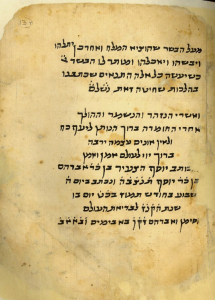

After enumerating other requirements for the shochet, the Karaite Sage Yisrael Ha’Maaravi described the theory of compensation’s application to shechitah as follows: “And [the shochet] should believe that an animal has a good compensation in place of its pain. And if the shochet does not meet these specifications, it is forbidden for him to perform shechitah, and it is forbidden to eat from his shechitah – both for himself and others.” (Translation by Ya’qov Walker.)

The top of this page of Hakham Yisrael Ha’Mara’aravi’s laws of shechita explains the requirement of compensation.

(Photo from Library of Congress.)

In the Rabbinic community, the theory of compensation died, for all intents and purposes, with with Maimonides who disavowed the doctrine. But the Karaite community of Egypt, Eres Yisrael, and Syria held on to the theory of compensation for centuries.

In contrast, the Karaites Crimea, Eastern Europe and Byzantium rejected the theory – especially after Aharon ben Eliyahu’s halakhic work Gan Eden held that a slaughterer need not adhere to the theory of compensation.

But Jews will be Jews, and there remained a rift. The rift came to a head in the 17th century when the Karaites of Crimea, Eastern Europe and Byzantium (who rejected the theory of compensation) and the Karaites of Egypt, Eres Yisrael and Syria (who accepted the theory of compensation) refused to eat meat slaughtered by the other community. This refusal was based on the fact that each community believed that the slaughterers of the other community held the wrong theology.

This is frustrating on many levels – not the least of which is that the Karaites were (and are) too few to be divided.

Well, I am a Karaite from Egypt and I don’t really know what I think about the theory of compensation; but I do know that I will eat properly slaughtered meat by any Karaite from any country, regardless of whether he or she accepts the theory of compensation. And if there is a Karaite shochet or shochetet from Europe or Byzantium out there, I’m ready to place my first order.

I happen to come from an orthodox family from Syria. However, obviously, I am a karaite. And to me, the concept of having intention of compensation seems totally absurd. Firstly, the Torah never mentions such a concept as compensation. Secondly, even if the concept of compensation is true, the Torah doesn’t command that we must think of thereof nor does it say that it would be invalid without proper thought. We, as karaites, should not assume the necessity of ״thought” unless the Torah makes a mention thereof. Otherwise, how are we better than the rabbinates!?

Hi Isaac,

What are the limits though? Would you eat properly slaughtered meat performed by a gentile? What if the gentile was (in his mind) sacrificing the meat to another deity? Or was (in his mind) believing that every act he does glorifies the deity, even if the act was not a sacrifice.

What about if a Jew is a non-believer? Or if a Jew believes that the Rebbe was the messiah?

Ok so as long as the slaughterer doesn’t seem to be slaughtering to a foreign deity, it’s “kosher”. There’s no reason to assume that the gentile is doing so in his mind, unless it is apparent from the circumstance. If he’s slaughtering in front of an alter or church, or he’s praying meanwhile, or he’s doing some strange things which seem like a ritual, then we should assume it’s for a foreign deity. Otherwise, if the gentile is just slaughtering the animal, there’s no reason to think it was for a foreign deity. Same would apply to a nonbeliever. ” if a jew believes the rebbe was the messiah” HAHA I’m right next to some right now, but they don’t idolize him, so it’s irrelevant. This is what seems logical to me.

I incline toward Isaac’s position. If we can agree that the Torah is ordering us in so many words that only we may slaughter for our own consumption, but yet we begin disqualifying a Jew’s Sheḥiṭah for reasons other than overt idol worship, there would be no end to the additions we would be placing on top of the Torah’s own commandments, and such strictness invalidates the point of being a Qaraite. As things stand now, the traditional Qaraite set of demands that must be met for a slaughter to be fit for consumption already exceeds the Torah’s criteria as seen through the demand that the slaughterer subscribe to all 10 Principles of Faith, for instance, thus being a forbidden addition to the Torah.

The Torah does NOT require the slaughterer to be an Israeli. The slaughterer can be a gentile. In Genesis 18:7, Abraham gave a calf to his servant to prepare for meat for the three heavenly visitors. In no way does the Torah find fault with the servants slaughtering or preparing meat for the three visitors or for Israelis. If a gentile tells you that he sacrificed a clean animal or even prepared vegetarian food to an idol, then do not eat of his food because he would then be asking you to worship his idol.

Nonetheless, if he does sacrifice the animal to an idol BUT does NOT tell you beforehand that he did it in such a way, the food is still acceptable by way of inference from the Torah. The reason is that an idol is a false god and thus has no power to spook the food. To believe in such is idolatry by itself. The Torah does not burden us with finding out what prayer the food preparer–Israeli or gentile–had in his mind. If you eat food that the preparer tells you beforehand was sacrificed to other gods, you are engaging in worship of his gods. You can openly tell him that you denounce his god and still eat the food, but that may cost you your life, so I don’t recommend it.

All that the Torah requires is that meat be from clean animals, his blood be spilled on the ground, and the fat be discarded. The animal must also not be fed the remains of other slaughtered animals because such remains contain fat, which the Torah requires to be discarded. We know from modern medicine that such feeding of animals will expose both the animals and the human consumers to prionic diseases such as mad cow disease.

The Torah does not even require the gruesome slitting of the animal’s throat. You can simply insert a sharp blade to the side of the animal’s neck to open his carotid artery for him to die with the least possible pain.

I had used to steadfastly maintain that the Torah does not demand the slaughterer to be an Israelite. But my attention was turned to how the wording in Devarim/Deut. 12 is directed strictly to Israelites, so therefore just as the commandment to the Israelites to make for themselves Ṣiṣiyot on their garments’ corners cannot be delegated to a gentile, so to with the slaughter commandments through a Hayqesh (reasoning through analogy).

I am afraid the matter is more complex than you make it out to be since the attempt to prevent animal suffering is a clear theme in the Torah, so it follows that any way to decrease it should be undertaken. This is why most every Qaraite expects the animals they consume to not have been on the verge of death or ill or pregnant during slaughter; the Torah actually forbids slaughtering a parent and its offspring on the say day, even if they are still in its womb.

It is not all fat that must be discarded from the slaughtered animal but the Ḥelev-fats which the Torah names.

Your concluding arguments are doubtful. They will be fully justified only if you finally conduct a well controlled experiment where you compare your proposed method to the traditional Qaraite one. In particular, you need to check just how much blood each method drains out of the animal and how fast it occurs. IF IF IF you will prove correct, every Torah-true Jew and gentile of conscience should then demand of the Qaraites to transition to this method. Until you are able to prove your claims there is no reason to believe that your slaughter method achieves the removal of just as much or more blood than the Qaraite method.

Is there any further elucidation on the concept of “Compensation”?. Is this the animals afterlife spiritual compensation or perhaps next life reincarnate compensation (if believed by Karaite theology)? Or how about compensation for that particular species as a whole for future survival and survival of humans?

Thanks.

See my response to Nathanael.

I really don’t understand concepts of “the compensation” of slaughtered animals. Can you explain this?

In Karaite slaughter, is the animal’s blood collected and placed in a consecrated location?

I understood it to mean that the animal is rewarded for it’s suffering, via our consumption of it. And I think that the blood just needs to be covered with any dirt that you poor the blood on.

Isaac, see my response to Nathanael below.

Here is the R’ Saadia’s thoughts on this (as translated by Lasker):

I will make this matter understandable and say: the Creator has decreed that every animal will die, and has given every human an allotted time of life, and He has made allotted times of life for the animals until the time of their slaughter, setting up slaughter in place of [natural] death. If there were in the [act of] slaughter a greater pain than the pain of [natural] death, [God] knows this; and therefore it is proper that He compensate the animal for the amount of pain that was greater than in [natural] death. We say this is so when the case of additional [suffering] is known from the intellect and not from prophecy.”

(Lasker, From Judah Hadassi to Elijah Bashyatchi, Brill, p. 203.)

I just finished reading “from Judah Hadassi to Elijah Bashyatchi”, very interesting stuff in there, though Lasker doesn’t think much of us Modern Karaites.

Why do you say that?

His ending comments are not too flattering. He doesn’t think we are flexible (which he deems important), we are stuck in the past, we haven’t “updated” our philosophy to include Kant, Hegel, Existentialism, etc. I get the feeling he doesn’t feel that Karaite Judaism has the ability to speak to the needs of the “Modern Person”. At least that’s how I understand his view given what he wrote.

karaites must adhere to the words of the Torah. Modernizing or remaining traditional is irrelevant.

Thank you so much Shawn for the books that you have given to us to read, what a awesome misvot before the Most High.

I do have a question pertaining to having a bible to read. Such as we were given a Hebrew Bible it is the J.P.S. study bible… from a friend, but the problem is that their is so much of the rabbinical viewpoints of which really hinders the main topics within itself. I have the 1917 JPS but really would like a better form of a study bible included…would you know of any?? Thank you again, From Dale and Elena Miller p.s. we were blessed in meeting you at your congregation. Please say hi to everyone for us…