My Birkat brings all the boys to the yard, I can teach and I won’t even charge. Or something like that. About a year ago, I was caught in what appeared at the time to be a mind-numbing debate over some minutiae regarding a single word in the Birkat Hamazon that appears in Karaite texts. It turns out the debate was not mind-numbing at all and a simple look through the Cairo Geniza would have solved the whole issue and explained a whole lot more.

My Birkat brings all the boys to the yard, I can teach and I won’t even charge. Or something like that. About a year ago, I was caught in what appeared at the time to be a mind-numbing debate over some minutiae regarding a single word in the Birkat Hamazon that appears in Karaite texts. It turns out the debate was not mind-numbing at all and a simple look through the Cairo Geniza would have solved the whole issue and explained a whole lot more.

As I will explain below, what was a debate over two vowels in a single word in a blessing, led me on an amazing journey showcasing how Karaites preserved a very ancient form of the Birkat Hamazon. I know of no other modern sources with this similar text, but if you are part of a community that has a similar Birkat (or know of historic communities with something similar), I want to hear from you.

First, some context: I was putting together that beautiful new abbreviated blessings book, and at the advice of Nir Nissim, I decided to print the entire Birkat Hamazon for the Sabbath Day (not the abbreviated version that was in the first blessing book). Nir gave me the text as it was printed in the zimron, song book, used for his wedding weekend. James Walker was helping transcribe and translate the additional portions of blessing, he observed that something seemed off in the vocalization in the precedent he was using.

The text in the Zimron had the words veshulḥanekha ‘arokh lakkol, and set your table for all.

James had a hunch that the text should read ‘arukh (not ‘arokh), but wasn’t firm. Nir told me that regardless of what was printed in the zimron, I should follow what was in the Vilna Siddur. So, I checked the Vilna siddur and another Karaite siddur and indeed they said, ‘arukh not ‘arokh.

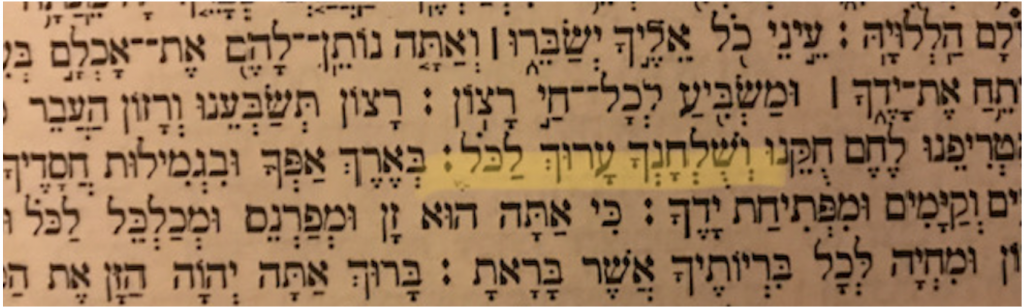

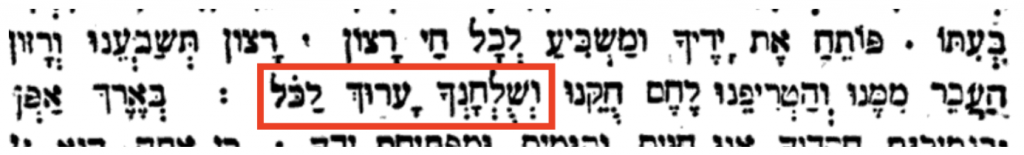

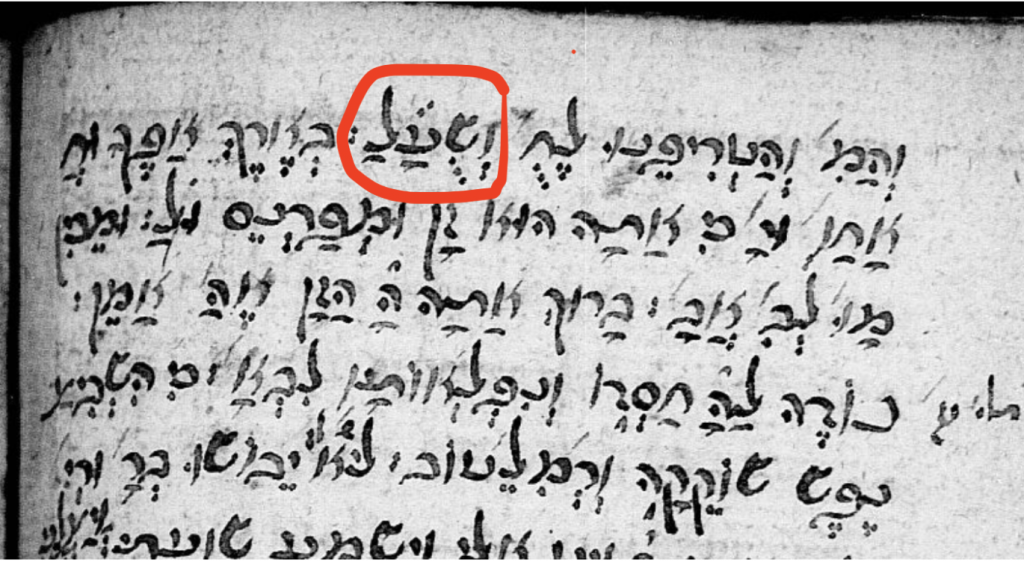

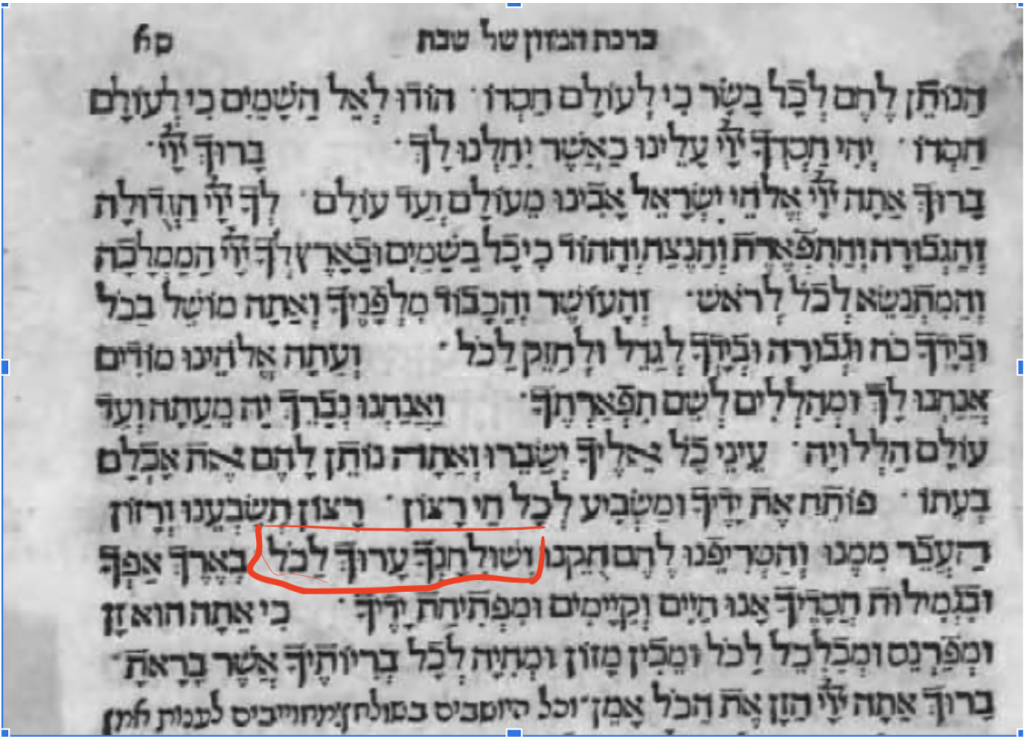

Here is the Shabbat Day Birkat Hamazon from Vilna Karaite Siddur (1891)

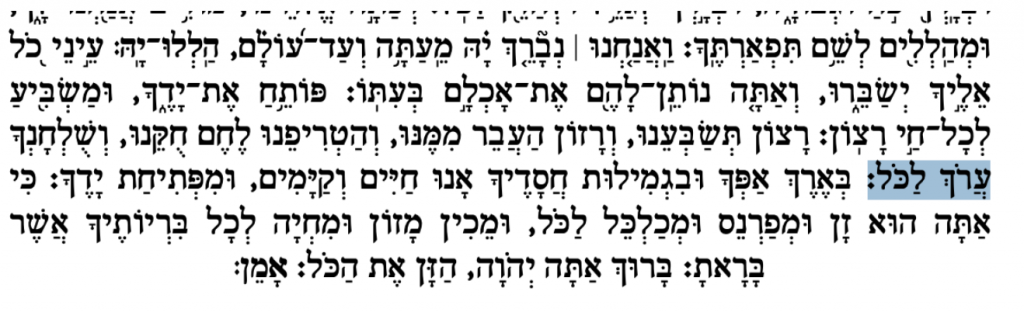

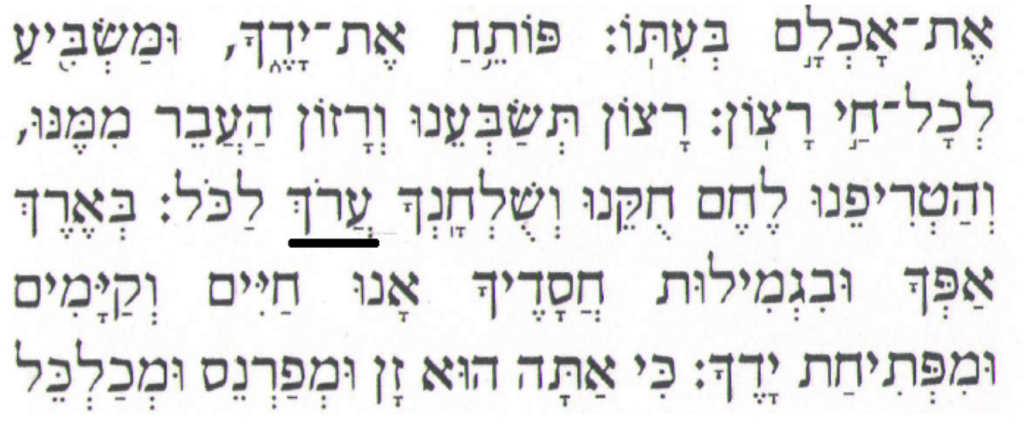

Here is the Erev Shavuot Birkat Hamazon from the Gözleve Karaite Siddur (1836):

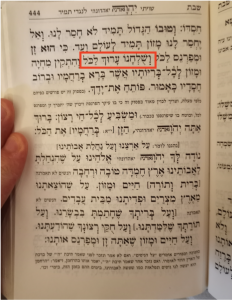

It turns out that the zimron Nir gave me was not the only place that had ‘arokh. It also appears in this modern publication of Karaite mourning rituals.

The difference between ‘arokh and ‘arukh is indeed minuscule: ‘arokh is in the imperative “set your table for all” and ‘arukh is a passive participle “your table (is) set for all”. So which is “correct”?

Usually, in cases like these I just ask Gabriel Wasserman (who helps me with virtually all my liturgy work) what to do. Gabriel advised me to ask the Karaites in Israel what to print.

So, I asked Eli Shemuel and Neria Ha-roeh and Hakham Moshe Firrouz and Nir Nissim. And there I was – in the middle of discussions about whether it should be ‘arukh or ‘arokh. (A special shout out to Neria, because the new blessing book – and so many others – would not have been possible without his work on the earlier editions.)

I need to point out that *no one* was arguing that ‘arokh was supported by a historical text. Even those pushing for ‘arokh acknowledged that ‘arokh was a modern change, made during the current generation (within the last few years), and the only question was whether this change made it better.

The argument for the change was simple. The sentence reads: “Fill us with satiety, and keep famine away from us, and feed us our constant bread, and —” And what? Surely it is more “logical” to follow these three requests with a fourth request: “and set [‘arokh] your table for all.” Yes, the historical text reads “and your table is set [‘arukh] for all,” but this breaks the parallelism, and thus is awkward.

I became convinced that ‘arokh, the imperative, was probably a better reading – though I was given no historical support for this reading. So we printed ‘arokh in the Abbreviated Blessings Book we recently published and in the forthcoming Asifat Shalom, on Karaite mourning rituals.

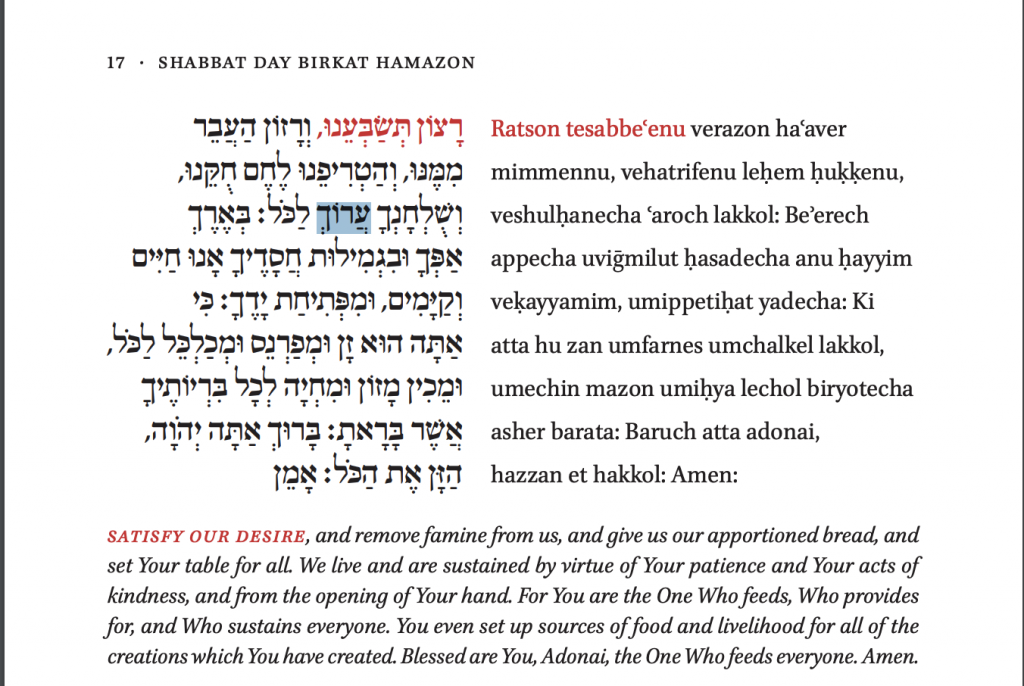

Here is what is in that beautiful new blessings book, which you can buy here:

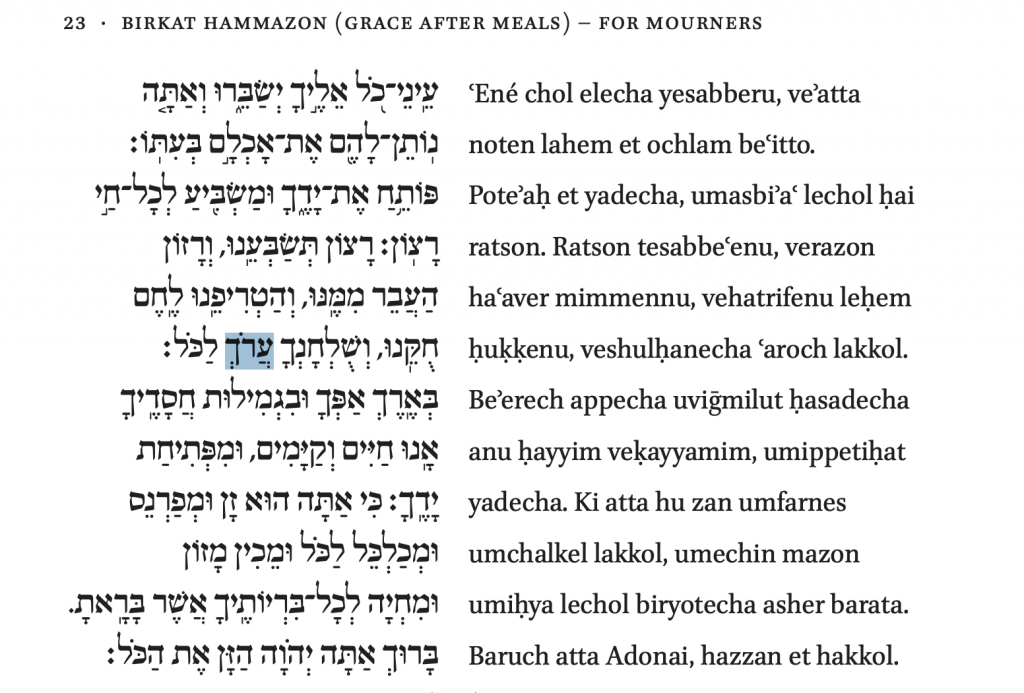

And here is what is in the forthcoming beautiful book on Karaite mourning rituals.

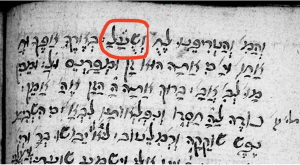

But even though I was convinced that ‘arokh was a better fit, I was uneasy about this. Because there was even a handwritten siddur of Karaite blessings (sadly, I don’t recall where or when it was produced) that also said ‘arukh. So, if this indeed was “wrong” – the word was accepted as ‘arukh across all textual witnesses. In this handwritten siddur, the words veshulḥanekha ‘arukh lakkol are abbreviated. You can tell it is ‘arukh, because it is vocalized with a kamatz under the ‘ayin (‘arukh has a kamatz, whereas ‘arokh would have a ḥataf-pataḥ).

Although I was uneasy about it, I lost very little sleep over it. I’ve learned over the years that texts bounce around communities and get emended (intentionally or unintentionally). I’ve previously shown various versions of She’arekha, and how the Karaite version happens to preserve a more historical form of this rabbanite poem. I’ve also explained how Karaites emended the polemic in ibn Ezra’s Ki Eshmera Shabbat. We’ve even debated whether Karaites censored enough of the Rabbanite lamentation for Ekha. Besides, we are dealing here with non-biblical text, where change happens all the time. It’s not as if we would be printing an error in the biblical text of a siddur, as the Karaites have done for centuries.

So, I just had to make a decision and move on. That’s what I did.

As an aside, I did not know this at the time, but apparently a very similar phrase appears not only in Karaite liturgical books, but also in Sephardic Rabbanite ones — and they also read ‘arukh (for reasons we will see below).

Here is the image of a Sephardi siddur that follows the Moroccan tradition: Siddur Avot U-vanim, ed. Meir Eleazar Atia, Jerusalem: Qeren Ahavat Qedumim (early 21st century):

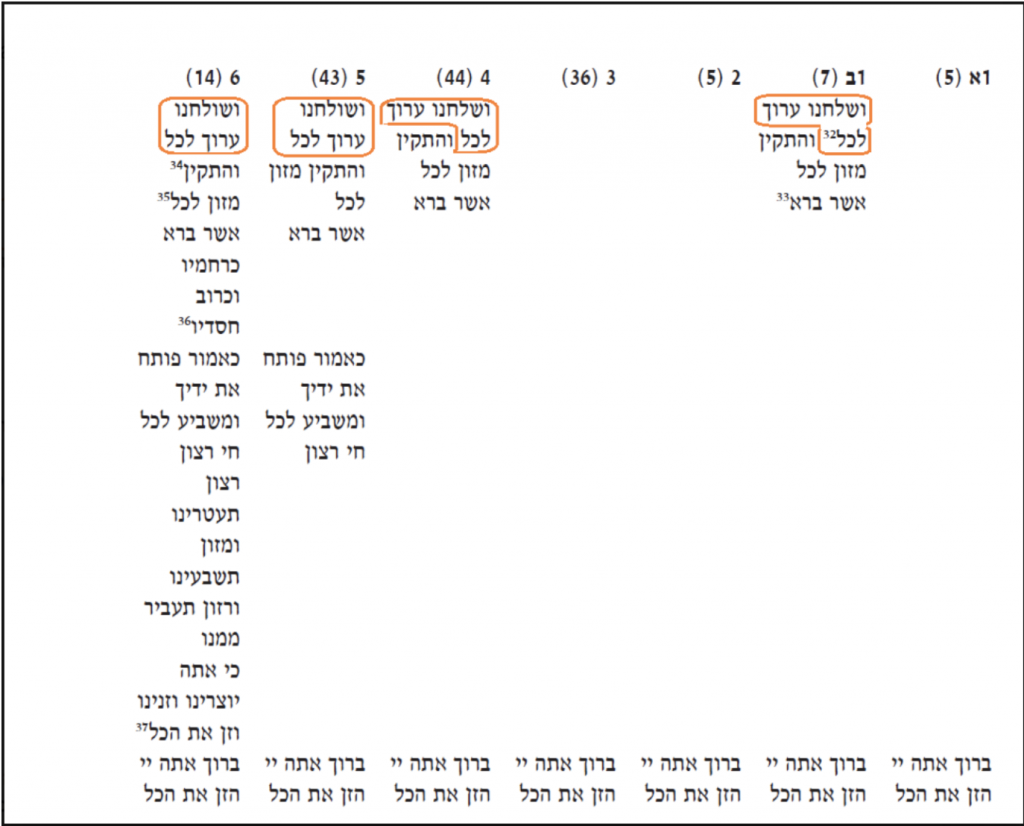

I had mostly forgotten about this discussion over ‘arukh and ‘arokh until just last week when I received an email from Gabriel with the following chart from this article by Avi Shmidman and Uri Erlich (נוסחה הקדום של ‘ברכת הזן’ לאור קטעי הסידורים מן הגניזה הקהירית, in Ginzei Qedem 15 [2019]):

Remember that I said above that the phrase in the printed Sephardic Rabbanite text was “very similar” — not identical — to the Karaite text? As you can see here, all these texts from the Geniza say ve-shulḥano ‘arukh lakkol, and His table is set for all, in the third person, instead of what was printed in historical Karaite texts, ve-shulḥanekha ‘arukh lakkol, and your table is set for all. And the Sephardic text reads just as in these texts from the Geniza. Since God is being addressed in the third person, the word cannot be an imperative, addressing God directly, but must be a participle describing God’s table.

Each of the six columns in this table presents one text family. There are many individual manuscripts in the Geniza that contain the text of any one family.

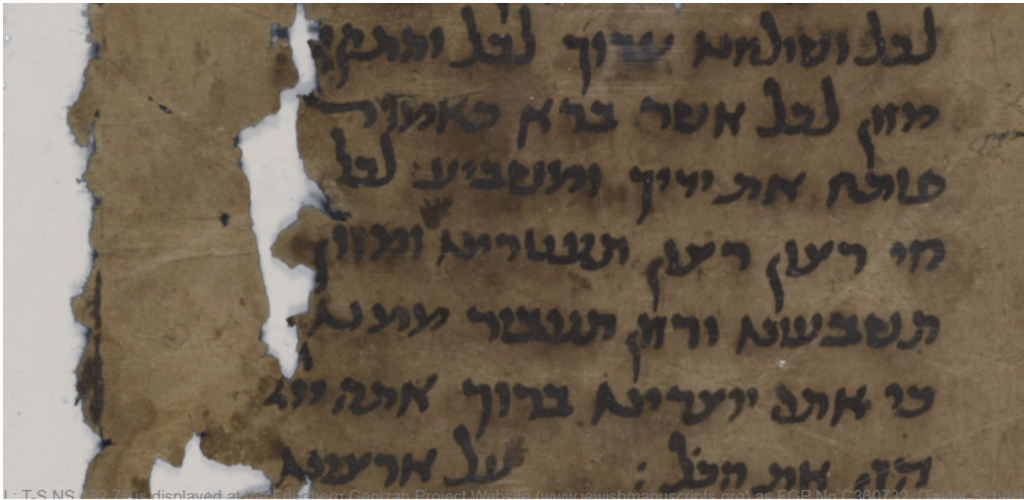

Here is an example of a Geniza fragment of Family #6, the leftmost column; its manuscript number is Cambridge T-S NS 152.77 (image from the website of the Friedberg Genizah Project):

Note that this is part of the family of the leftmost column, but not the same text. In the image, you can see the words:

לכל ושולחנו ערוך לכל והתקין מזון לכל אשר ברא כאמור פותח את ידיך ומשביע לכל חי רצון רצון תעטרינו ומזון תשבעינו ורזון תעביר ממנו כי אתה יוצרינו ברוך אתה ייי הזן את הכל

…lakkol veshulḥano ‘arukh lakkol vehitḳin mazon lakkol asher bara ka’amur poteaḥ et yadekha umasbia‘ lekhol ḥai ratson ratson te‘atterenu umazon tesabbe‘enu verazon ta‘avir mimmennu ki atta yotserenu, barukh atta adonai hazzan et hakkol.

“…to all, and his table is set for all, and he has prepared food for everything that he has created, as it is said: Thou openest up thy hand and satsifiest every living thing with satisfaction. With satisfaction crown us, and with food sustain us, and famine keep away from us, for you are our creator. Blessed are you O Lord, who feeds all.”

From all this, we see that the historical form of the line was in the third person (as it still is in the Sephardic Rabbanite text today), and therefore, necessarily, the relevant word was ‘arukh (because ‘arokh is an imperative – in the second person – and you cannot use the second person imperative to direct a third person) . This explains why Karaite texts traditionally have ‘arukh – because that was the word used in the historical form of the blessing.

BUT. There is always a but.

That does not mean that we needed to print ‘arukh today. Why? Because the text in the Geniza (and in Sephardic siddurim) is “His table is set for all”, and the “traditional” version in Karaite texts is “your table is set for all.” Maybe once the text got changed to “Your” from “His” it is better to change it from ‘arukh to ‘arokh to match the second person nature of the passage which makes a series of requests. The change from ‘arukh, is set, to ‘arokh, set, is no less legitimate (and no more drastic) than the change from “His table” to “Your table.”

I’ve come to realize that the best thing I can do is just make decisions and move on. So I am making a decision. I’m leaving the Abbreviated Blessings Book as it is, since it is already printed. I’m leaving An Ingathering of Peace as it is, since it is already typeset. But I am going to print ‘arukh in all future printings, including the upcoming songs and blessings for erev shabbat and weddings. Or maybe I won’t. I can figure that out later.

If I revert back to ‘arukh in future publications, people who learn the blessing from An Ingathering of Peace and The Abbreviated Blessings Book, one the one hand, and from future publications, on the other, would be at odds over what is the “correct” blessing. May we have so many people that we can argue about these things!

But people who have read this post will be able to explain exactly why they are different and I hope people who read this post will also admonish all and remind them that there is no such thing as the “correct” text with respect to a blessing that has changed many times and in many ways over the centuries.

***

For those who want a theory as to how all these changes occurred, Gabriel suggested the following:

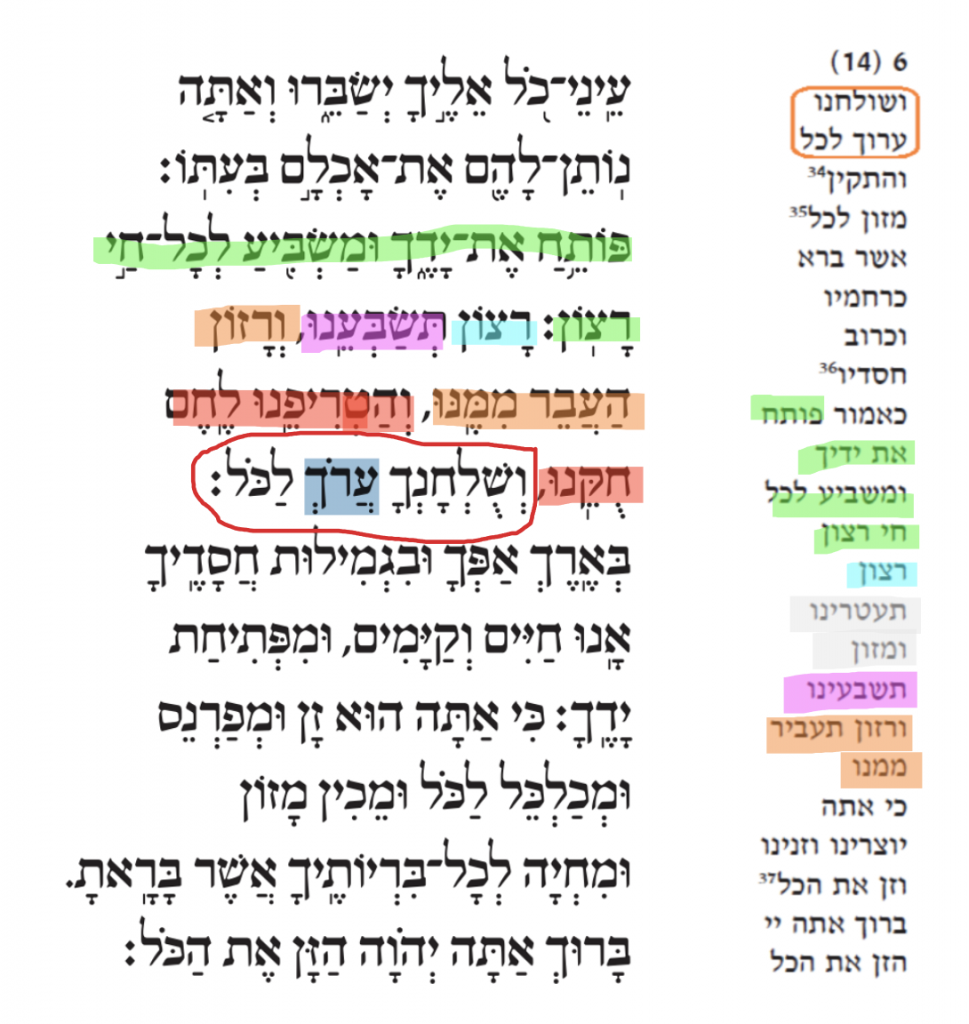

In Geniza fragments, we find that this paragraph of Birkat Hamazon begins (after the opening words ברוך אתה ה’ אלהינו מלך העולם, “Blessed are You O Lord our God, king of the universe”) in the third person, including the line ושולחנו ערוך לכל, “and his table is set for all”; then it backs up this point, that God provides sustenance to all, by quoting Psalms 145:16: פותח את ידך ומשביע לכל חי רצון: Thou openest up thy hand and satsifiest every living thing with satisfaction. Then follows a short poem, of one quatrain (four-line stanza):

רצון תעטרנו

ומזון תשבענו

ורזון תעביר ממנו

כי אתה יוצרנו

Each line rhymes with the suffix -nu, “us”, and thus can be translated into English — slightly awkwardly — thus:

With satisfaction crown us,

And with food sustain us,

And famine keep away from us,

For you are the creator of us.

Here is a mark-up of the relevant portion of the Karaite birkat hamazon and the left-most column from the article by Avi Shmidman and Uri Erlich.

Note also that the first word of the poem, ratson (“satisfaction”), רצון, repeats the final word of the biblical verse that immediately precedes it (פותח את ידך ומשביע לכל חי רצון). This is called anadiplosis, and it is a common phenomenon in Hebrew liturgical poetry; this is especially common when non-Biblical poetry quotes a Biblical verse and then continues with its own non-Biblical text, because the anadiplosis is a way to link the non-Biblical to the Biblical text.

For some reason, the Karaite text has detached the phrase veshulḥano ‘arukh lakkol from its position before the verse from Psalm 145, and placed it afterwards, as the final line of the brief poem, thus replacing the line ki atta yotserenu (“for you are the creator of us”). This disrupts the rhyme; but, more jarringly, it shifts from second person to third person. So, Gabriel hypothesizes, at some point after the phrase veshulḥano ‘arukh lakkol was moved to this position, someone changed the suffix in veshulḥano, “and his table,” to read veshulḥanekha, “and your table,” thus smoothing out the discrepancy between second and third person. But they never changed the participle form of ‘arukh (“is set”) to the imperative ‘arokh (“set”)

This change from veshulḥano to veshulḥanekha, took place no later than 1528, because this is the text in the Karaite Siddur printed in Venice in that year:

The change fromveshulḥano to veshulḥanekha removed the jolt from second to third person, but it retained a second awkwardness caused by this placement of the line, namely, three requests followed by the statement “and your table is set for all”. As far as we know, this second awkwardness did not bother anyone until the 21st century, when some Karaites in Israel decided to change ‘arukh to ‘arokh, turning this line into a fourth request.

When we look at medieval and early modern prayerbooks, we can see how liturgical texts changed, and make hypotheses about how, when, and why these changes were made. But in this instance, the change is taking place in the 21st century, and we don’t need to hypothesize about it — we can see it taking place in front of our very eyes. Wow!!!!!

There is something else exciting here, and this is relevant to the title of this post. The Karaite Birkat Hamazon, as printed in the Venice edition and all subsequent printings, preserves the lines רצון תשבענו ורזון העבר ממנו והטריפנו לחם חקנו (“With satisfaction sustain us, And famine keep away from us, and with food sustain us, And our constant bread feed us”) and ושולחנך ערוך לכל (“and your table is set for all”) — yes, in a somewhat different form from how they are in the Geniza, but still very recognizable. The Karaite Siddur was printed in Venice, a European city, for the Karaite community of Constantinople, another European city. As far as I know, no Rabbanites in Europe, certainly not by the early modern period, preserved the first of these lines. The second line was preserved by some European Rabbanites, in Spain — but not by Ashkenazic Rabbanites, and, more importantly, not by Romaniote (Greek-Speaking) Rabbanites, the local Greek Rabbanites of the Byzantine Empire (where Constantinople and the Karaites printing their siddur resided).

We know that the later medieval Karaites borrowed a lot of liturgical material from their Rabbanite neighbors. However, as far as we can tell, that is not what is going on here. The Karaite Jews here were being awesome, preserving their version of old Jewish texts of Birkat Hamazon, which the local Rabbanite Jews had apparently not preserved.

Hence the title of my post: My Birkat Hamazon may be “wrong”, not preserving texts exactly as they were a millennium ago, but it’s still “better than yours,” preserving ancient material that other Jewish communities have not preserved. Of course, I don’t really think my Birkat is better than yours, but it were, I’d have to charge.

***

For those interested in how a siddur changes: Such changes and emendations were particularly common among Ashkenazic siddur editors in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, who were constantly trying to impose Biblical grammar consistently on the liturgy of their tradition; in order to do so, they needed to make many small changes. Compare Robert Scheinberg, Seligmann Baer’s Seder Avodat Yisrael (1868): Liturgy, Ideology, and the Standardization of Nusah Ashkenaz (PhD Dissertation, JTS, 2020), p. 188:

There are, therefore, a variety of ways to understand the enterprise of Baer and his predecessors to remove these non-Biblical words. Some would classify this effort as a quest for a long-lost Urtext of the siddur that was written in pristine Biblical Hebrew, before it was corrupted with Rabbinic Hebrew words. Others might regard this endeavor as improving upon the liturgical work of the early Sages, who erroneously used non-Biblical words in their prayers; in other words, the text that was being created in the modern era by these grammarians was not a restoration, but rather was of higher linguistic quality than any previous version had ever been. A third perspective, more likely to be accepted by contemporary linguistic scholars, would hold that these grammarians were not correcting errors, but rather introducing errors. If the assumption that liturgical Hebrew avoids all non-Biblical words and forms is a fallacy, then when the grammarians modify the liturgy to make it conform to Biblical rules, they resemble the scribal copyists who thought that they were improving upon the quality of the text but whose “corrections” of “errors” were actually introductions of textual corruptions.

Thank you for a thoughtful and thorough article. It’s an eye opener in a way. A small variation in a word Can change the whole context and meaning.

However, I would like to ask about the prayer itself. Doesn’t it contain Biblical phrases?