I fell in love with this lamentation for the destruction of the Temple the moment I heard it. Love is complicated, though. And the history of this song is no exception. It appears in earlier Karaite sources – in a markedly different form. It was almost assuredly penned by a Rabbanite poet, but as far as I can tell has never appeared in any modern or even earlier printed Rabbanite siddurim. Oh – and the original poem calls for the destruction of non-Jewish Nations (as does the current version in the Karaite siddur, albeit more limited than in the original). Yikes.

I fell in love with this lamentation for the destruction of the Temple the moment I heard it. Love is complicated, though. And the history of this song is no exception. It appears in earlier Karaite sources – in a markedly different form. It was almost assuredly penned by a Rabbanite poet, but as far as I can tell has never appeared in any modern or even earlier printed Rabbanite siddurim. Oh – and the original poem calls for the destruction of non-Jewish Nations (as does the current version in the Karaite siddur, albeit more limited than in the original). Yikes.

At the end of this post I suggest a way to remove the last remaining call for destruction.

First – The Poem

But for now, listen to the song as preserved in the Karaite prayer book. And throughout this post, I’ll be asking you to vote on certain items.

You can listen here:

I was immediately drawn to the meter and rhyme of the poem from the first two words – Eyaluti Begaluti. Beautiful symmetry.

I was struck by this internal rhyme, where the first two words of each line rhyme with each other. So much so that I had to share it with Dr. Gabriel Wasserman, whose expertise in Hebrew poetry and Tanakh has contributed to the knowledge I have been able to share with you in other posts – such as this one on She’arekha and this one on an error in the Karaite siddur.

I told Gabriel that I loved the meter especially at the start of each line and he responded immediately that the meter is the same as that of Shené Zetim (“Two Olives”) by the famous Rabbanite poet (and author of Shearekha) Solomon Ibn Gabirol. And indeed, you can sing Eyaluti Begaluti to the tune of Shené Zetim, and vice versa.

But then things got super interesting.

Second – Messing Up the Name of Vespasian

Gabriel first told me that whoever edited the poem for the 1891 Vilna Karaite siddur (the one in use today), for the siddur changed the vocalization of one of the Roman names in order to “Latinize” it, thus producing a form that was not at all historically used in Jewish communities. This is apparent in the line:

הֲמָמוּנִי : פְּצָעוּנִי : קֵסָר וֶאסְפָּֽסְיָנוֹס

Hamamuni petza’uni kesar vespaseyanos

(“They threw me into confusion, and wounded me — Caesar Vespasyanos.”)

He knew right away that the Hebrew should have read:

הֲמָמוּנִי : פְּצָעוּנִי : קֵסָר וְאַסְפָּֽסְיָנוֹס

Hamamuni Petza’uni kesar ve’aspaseyanos

(“They threw me into confusion, and wounded me — Caesar and Aspasyanos.”)

Note that the plural verb makes sense only with this reading.

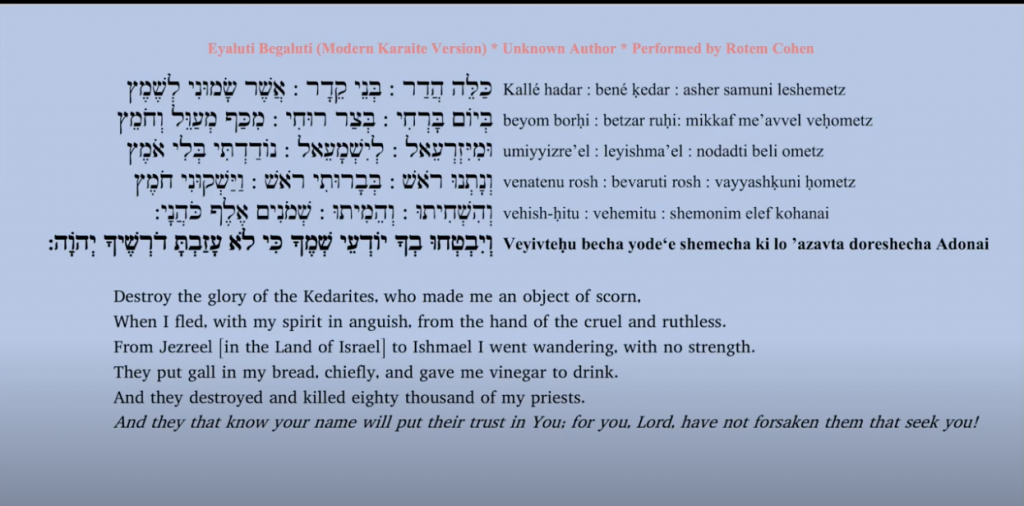

And indeed it does read this “correct” way – Ve’aspaseyanos – in the Vilna Karaite Siddur of 1868. (See images below.) I do not know why or how, but when Rotem Cohen recorded the song, he also read it with the proper Hebrew Ve’aspaseyanos.

For those – like me – who had no clue – “Aspasyanos” is the traditional Hebrew form of the name of the Roman Emperor Vespasian. The Latin form is Vespasianus. The editor of the 1891 Vilna volume evidently wanted to make the form in the poem fit the Latin pronunciation.

How did the editor sneak in this supposedly “more original” (but “incorrect” and foreign to Hebrew) form, without changing the consonants of the text? By taking advantage of the conjunction ve- (“and”) in the poem, and revocalizing the word such that the letter ve– formed not the conjunction, but part of the name! And thus the line became not: “Caesar and Aspasyanos” (qesar ve’aspaseyanos), but “Caesar Vespasyanos” (qesar vespaseyanos)!

Gabriel said that this exact emendation of Vespasian’s name appears in a nineteenth-century edition of a different Hebrew poem, “Nevukhadnetzar Akhalani”, from which he recognized it. (See images at the end of the post.) This fits into a general phenomenon of nineteenth century classical philology, of editing texts in ways that smooth out anomalies and oddities; in this case, the anomaly is that the Hebrew form does not match the Latin form. The problem is that the act of editing creates a new anomaly: a new Hebrew form, which never previously existed. (Note: below we will talk about censorship. This is not an example of censorship.)

Cool trick, Gabriel.

Third – Uncovering the Poem’s Origin – Sort of

I was amused that Gabriel’s deep knowledge had been able to spot what seems to be a relatively small emendation.

I then asked Gabriel to translate the poem for me – well for all of you and me, so you / we can understand what we are reading with this poem. But before he translated it, I had asked him to see if it had already been translated.

Gabriel was not familiar with the poem, so he checked in Davidson’s Famous Guide to Medieval Poetry. That’s not what it’s called. But it should be.

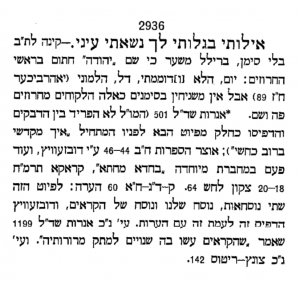

It has an interesting notation (see 5 lines from the bottom, which Gabriel has translated for us):

(And here is the translation for the last five lines of Hebrew.)

NOTE: This poem has two versions, our version and that of the Karaites. Dubsewitz published the two side-by-side, with notes. See also Shadal’s[1] letters, p. 1199, where he writes: ‘The Karaites made changes in this poem, to sweeten its bitterness.’ See also Zunz, Ritus, p. 142.”

The Karaites made changes in this poem to sweeten its bitterness?!?! What does this mean? And how did Shadal know that the Karaites changed it – as opposed to the Rabbanites (and that the Karaites inherited this changed version)? And who was Dubsewitz?

Even Gabriel hadn’t heard of Dubsewitz till we started looking into this.

Gabriel had a strong inclination that the poem was changed in Karaite hands – but as an academic, he knew his inclination was not definitive. So he set out to trace the origins of the poem and track it through its appearance in Karaite liturgy.

(Recall that this poem does not appear — as far as we know — in published/printed Rabbanite liturgy. However, it was used in a North African Rabbanite community as late as the eighteenth or nineteenth century, recited from handwritten books; the book is hardly legible, but if you want you can check it out here on page 50).

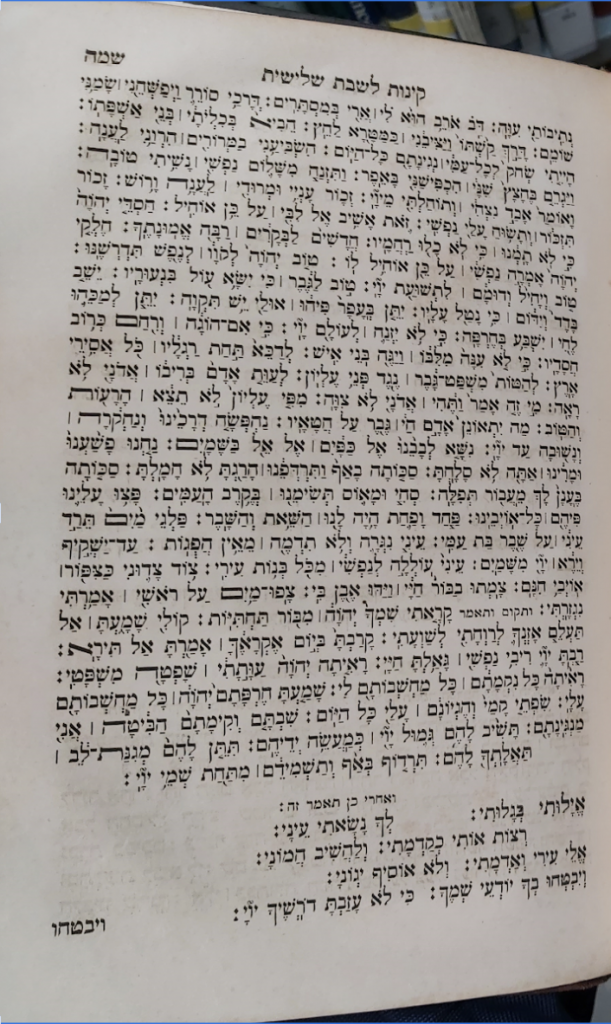

Fourth – The Karaite Venice Siddur of 1528 has the Bitter anti-Gentile Version

It turns out that the poem actually appears in the Venice Karaite Siddur in 1528. This version is for all intents and purposes the same version that appears in Rabbanite sources – the notable difference being that this version repeats the last line of the first stanzas as a refrain after each stanza. (It is quite likely that the Rabbanite communities did the same in their actual recitation of the poem, though they did not indicate the refrain in their manuscripts.)

The original version (in Karaite and Rabbanite sources) have this line as the refrain: Pursue them in anger, and destroy them, from under the heavens of the Lord! (Lamentations 3:66)

The censored version replaces this refrain from Lamentations – a refrain that fits the period of the year where we read from Lamentations – with another completely non-vengeful verse: Psalms 9:11 (And they that know Thy name will put their trust in Thee; for Thou, LORD, hast not forsaken them that seek Thee.)

This uncensored poem contains explicit references to overthrow Christian empires – and I will provide a translation for this “original” version in a link below. This is what Shadal meant when he wrote that the Karaites sweetened its bitterness: they replaced the bitter cries for vengeance with more neutral words.

(Note that even though the Venice Siddur is often attributed to the Karaite Sage Aaron ben Joseph, the siddur was printed 200 years after his death, and it is entirely possible and even likely that other texts were included in the siddur.)

Gabriel found the “uncensored” version in Karaite siddurs as late as 1805. We find the censored version in the Karaite siddur printed in Gözleve-Yevpatoria in 1836, so the change occurred between 1805 and 1836.

But that is not all. No, this story is just beginning. Kind of.

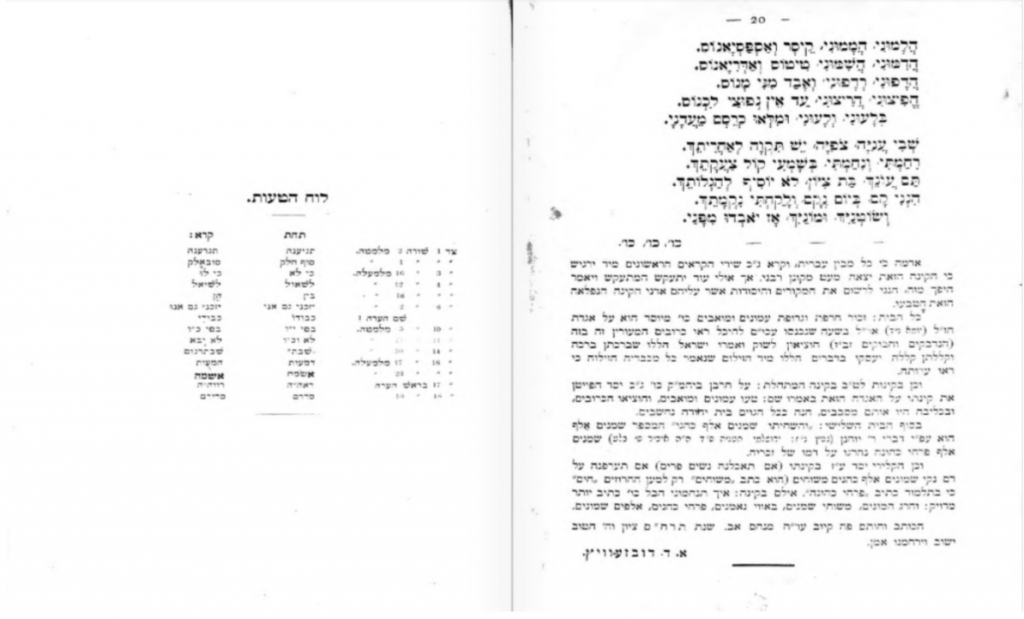

Fifth – A Rabbanite Scholar Encourages the Karaites to Restore the anti-Christian Elements

This poem and the Karaite change to the words caught the attention of Rabbanite Scholar Avraham Dov Dubsewitz. In 1888, he was looking at a version of the poem printed in the Karaite siddur of Vilna, 1868.

Dubsewitz then set out to teach the Karaites that the poem in this siddur had been corrupted, and he clearly thought he was doing them a favor by telling them this:

“The Karaites will gain from this, for they will fix this poem (when they publish their siddur again), which their copyists ruined, or perhaps they found an erroneous text. (Or another reason…)”

So – thinking back to my question of “how did Dubsewitz know that the Karaites changed it” – he actually did not know; he left open the possibility that they found an erroneous text.

The last part there – “(Or another reason . . . )” – needs some explanation, and Gabriel provided it to me: the third reason, which he will not mention here; this clearly refers to intentional censorship, something best not discussed outright, especially in the Russian Empire, hence the ellipsis at the end of his words.

Gabriel has translated for us Dubsewitz’ work – and you can read it here: Dubsevitz on Eyaluthi .

Well, that’s almost it for now.

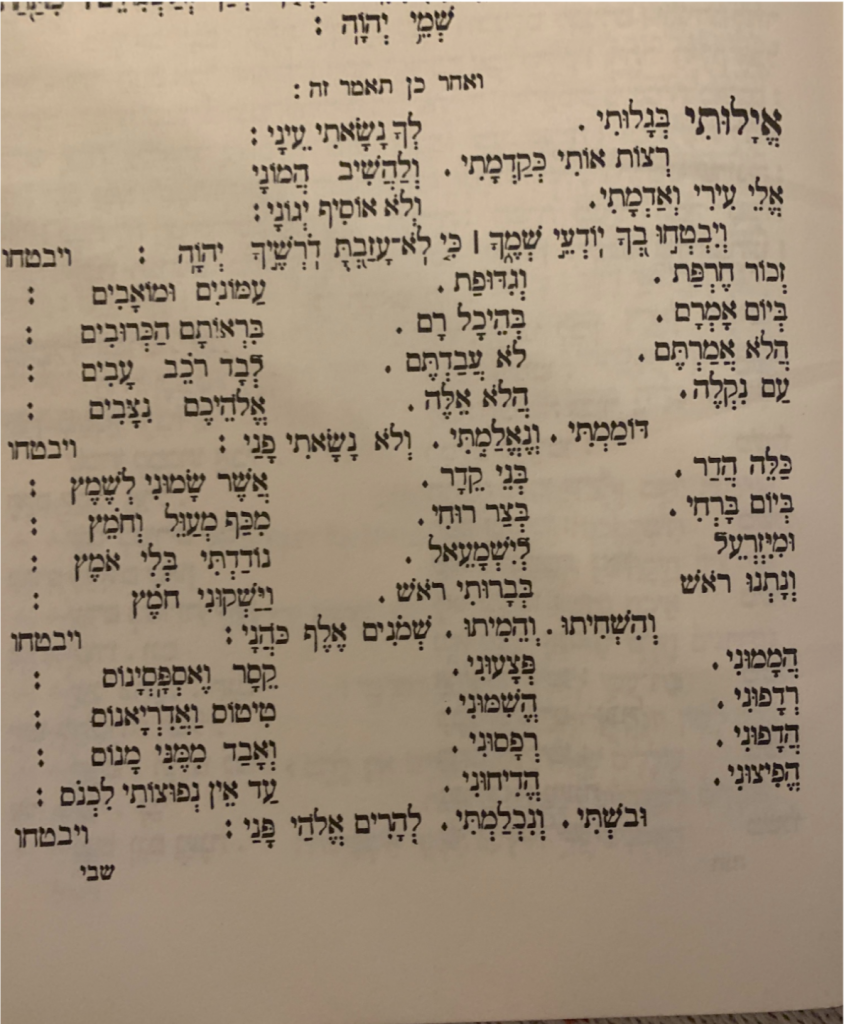

Sixth – The Remaining and Express anti-Islamic/anti-Ishmaelite Elements

I still have to show you and help remove the final call for the overthrow of a nation. The line in the original poem – and preserved in the Karaite edition in Vilna – calls for the destruction of Qedar, a specific reference to Islamic nations. (Russia, long at war with Turkey – which Qedar came to symbolize -, certainly didn’t mind calls for the destruction of Islamic nations.) Qedar was the second son of Ishmael.

And the reason this poem gives for the anti-Ishmaelite sentiment is that, according to rabbinic tradition, Ishmaelites treated the Israelites cruelly at the time of their exile from Jerusalem under the Babylonians, by dehydrating them to death; see the second and third line here. And Ishmael became a reference to and symbol for Islam in Jewish sources.

As Dubsewitz points out, this line rooted in the Talmud. Dubsewitz writes:

In the end of the third stanza: “And they destroyed eighty thousand of my priests” – the number 80,000 is based on the words of R. Jochanan (Gittin 57b; Yerushalmi Ta‘anith 4:5, Ekha Rabba on verse 2:2): “Eighty thousand young priests were killed for the blood of Zechariah.”

For background, according to Ekha Rabba, Proem §23, Nebudazaran killed 80,000 young priests. Nebuzaradan, a Babylonian, was a general of Nebuchadnezzar.

According to Midrash Tanḥuma (regular printed edition), Yithro §5 (and other rabbinic sources), when the Babylonians led the Israelites in chains into exile, they begged their captors to bring them by the way of the land of the Ishmaelites, their cousins; their captors indeed led them there, but the Ishmaelites treated them there with terrible cruelty, giving them very salty bread and brine, and containers filled not with water but with burning hot air.

For the record, I don’t know whether Nebuzaran killed 80,000 young priests. And I also do not know whether Ishmaelites dehydrated Israelites to death in the aftermath of the destruction of the First Temple. But since this is rooted in Rabbinic literature, I can guess that most Karaites in history had no clue about the significance of the 80,000 priests who were killed in the poem.

I do not have to guess – and I know with certainty – that the overwhelming majority of Karaites in Egypt didn’t know Hebrew, barely knew Tanakh, and certainly didn’t know poetry and had no clue what they were saying. But the great irony is that because of Russian censorship, the Karaites in Egypt were not allowed to call for the destruction of Christian nations, but were allowed to call for the destruction of Islamic/Ishmaelite nations – even if they did not understand what they were saying.

Here I note that the Karaite community of Cairo already has a history of censoring much much milder criticism of their muslim neighbors. For example, an earlier version of the Karaite Haggadah opens with lines praising God for saving the Karaites from the hand of Ishmael. But the Karaites of Egypt censored/changed these words.

Seventh – Trying to Censor the Rest of the Poem

Regardless of what you think, I won’t print liturgically any poem that calls for the destruction of any nation or people. So, I have asked Gabriel to help rewrite the following line – which is the first line in the stanza above:

כַּלֵּה הֲדַר : בְּנֵי קֵדָר : אֲשֶׁר שָׂמוּנִי לְשֶׁמֶץ

(Destroy the glory of the Kedarites, who made me an object of scorn.)

He came up with the following:

מְחֵה רֶשַׁע : בְּנֵי פֶשַׁע : אֲשֶׁר שָׂמוּנִי לְשֶׁמֶץ

(Wipe out the men of sin, who have made me an object of scorn.)

Next year, I will (hope to) print a compendium for Echa – and I may print this version. I note that even though this version replaces a call for destruction of an ethnic group with a call for destruction of sinners, my intent is NOT to equate that (or any) ethnic group with sinners. We needed something that keeps the internal rhyme (mehe resha’ : bene pesha’) and fits with the last part of the line (who made me an object of scorn). I am open to other suggestions.

And I note that the men of sin in context of the Karaite version of this poem could be Jews as well. And I may even change the line about 80,000 priests to solidify that interpretation. But this sounds like a lot of change just to preserve song that I never heard of more than 30 days ago. Maybe it’s a lost cause.

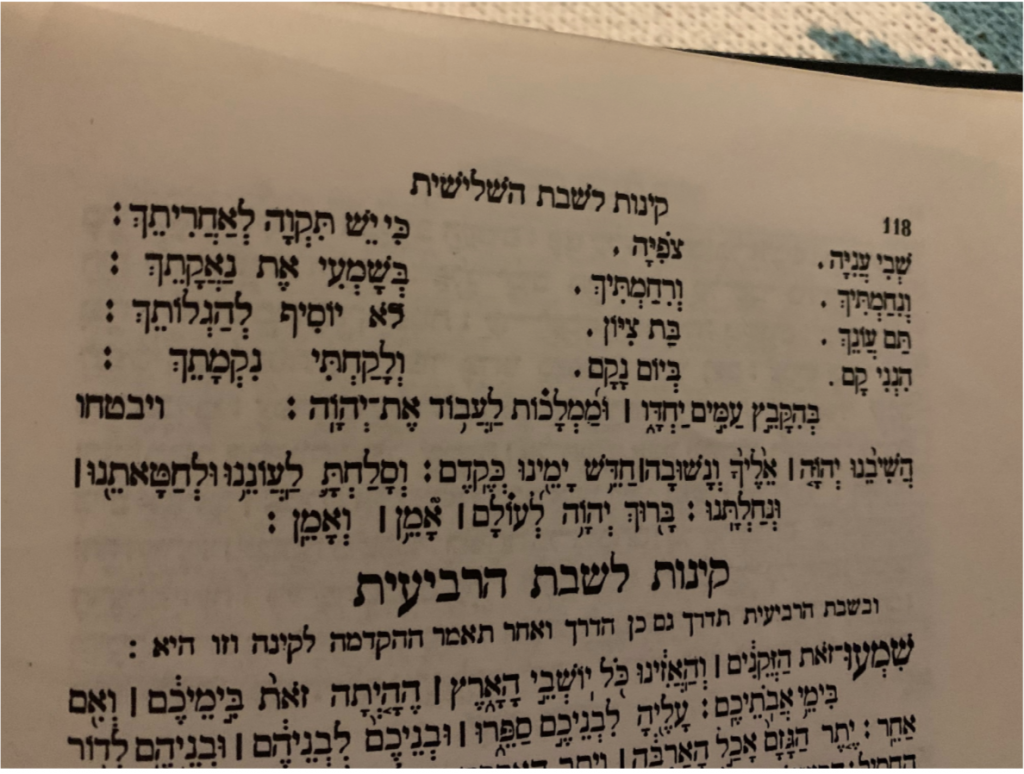

Remember this poem is usually recited in the Karaite tradition on the third Shabbat during Echa (it even says this in the Venice siddur 500 years ago). I for one am happy for the censorship and I hope you will sing it with the proposed, further emendation, for I don’t love calling for the destruction of nations.

Here you can see the censored versions of the poem translated: Eyaluthi Begaluthi (Vilna Hebrew) and Eyaluthi Begaluthi (Vilna Translation).

Note – I have not included an emended further censored version.

And below you can look at images of the siddurim referenced.

* * *

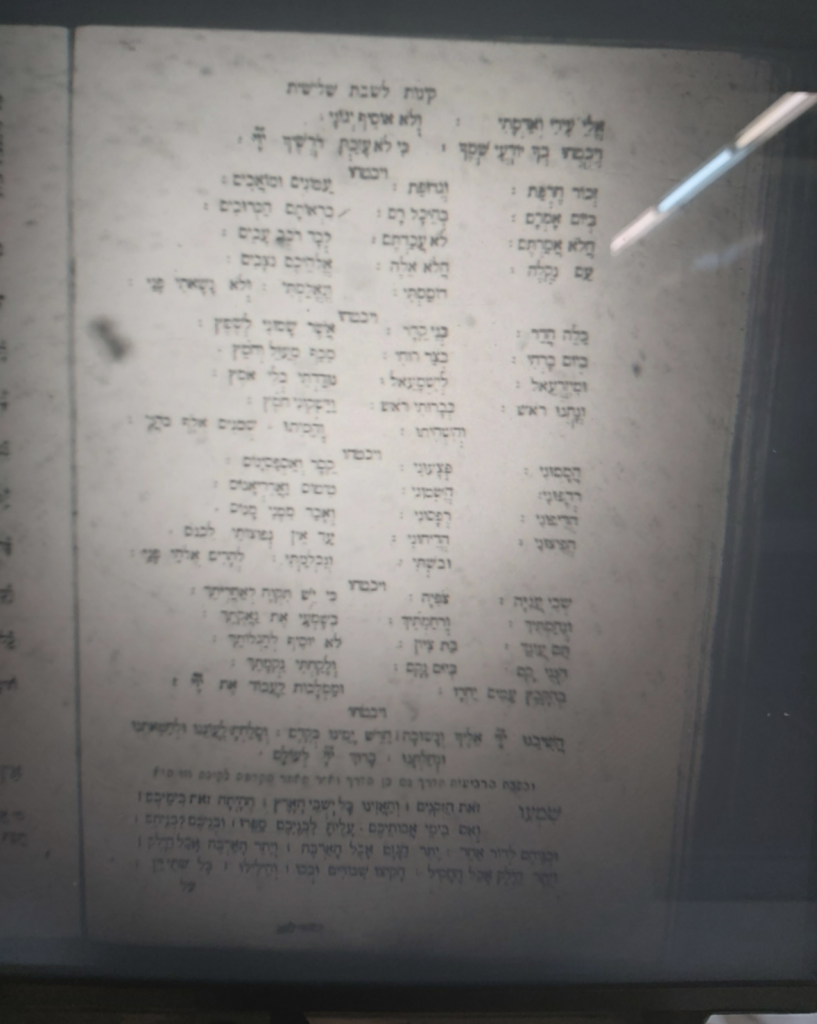

Venice Karaite Siddur, 1528:

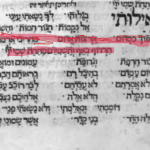

Chufut-Kale Karaite Siddur, 1737:

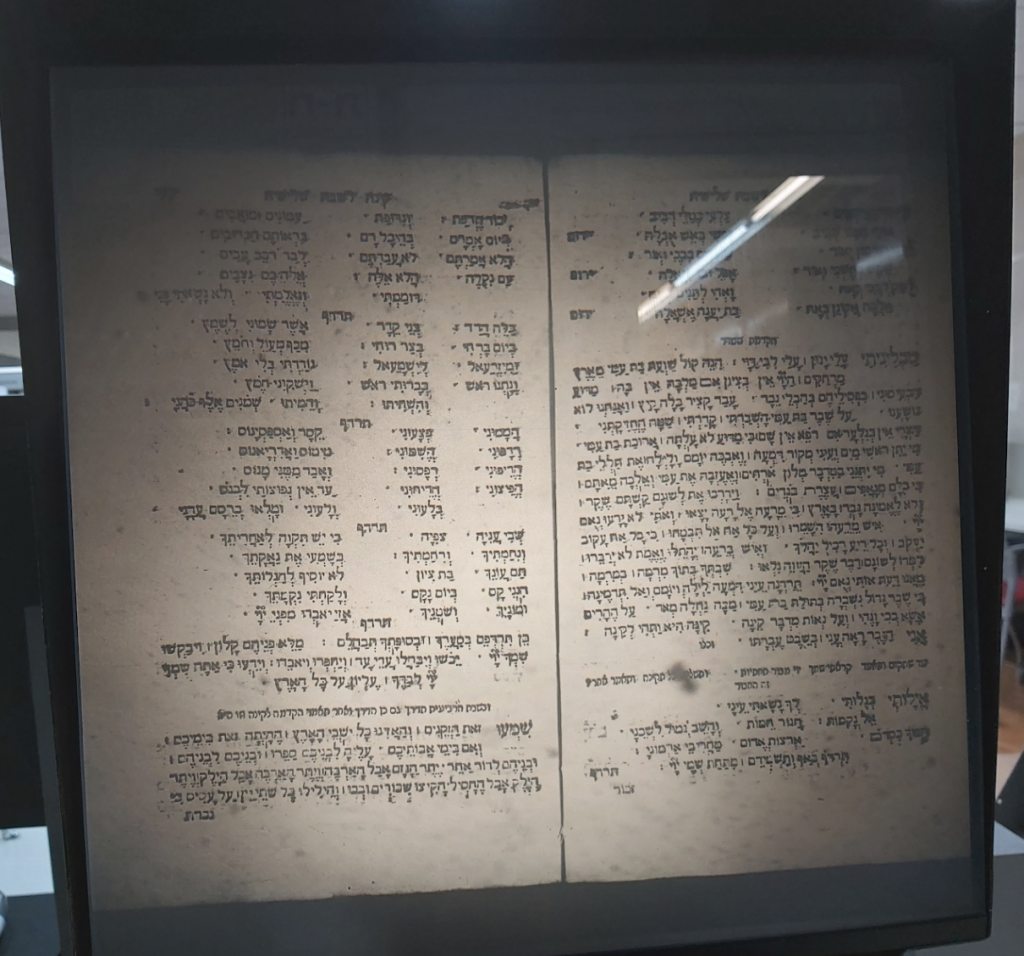

Chufut-Kale Karaite Siddur, 1805:

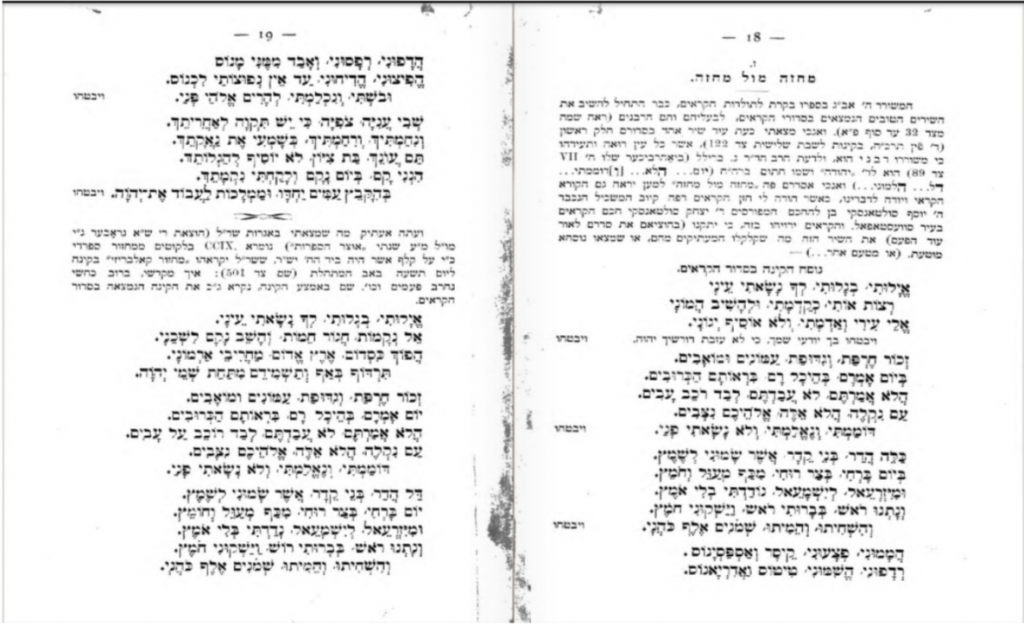

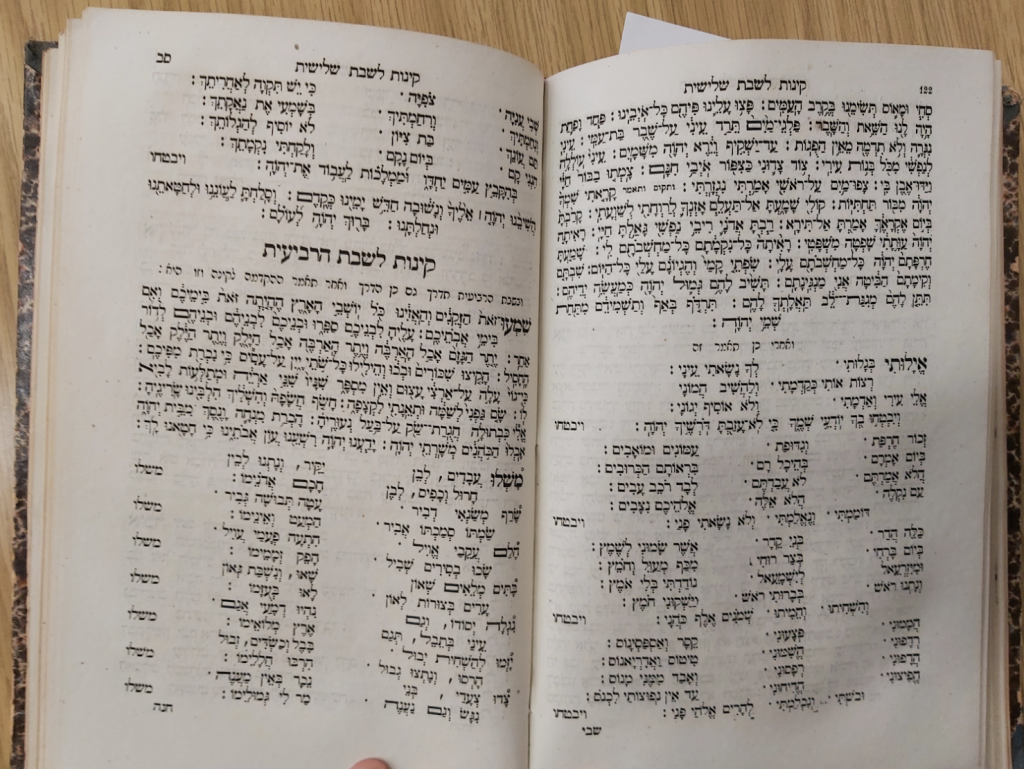

Karaite Siddur, Gözleve-Yevpatoria, 1836 (two pages):

Karaite Siddur, Gözleve-Yevpatoria, 1836 (page 1 / 2)

Karaite Siddur, Vienna 1854 (two pages):

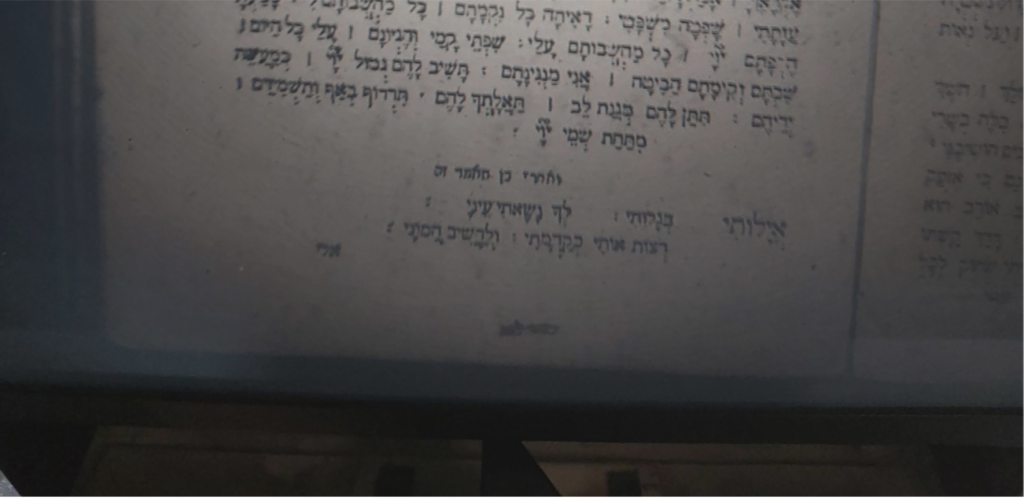

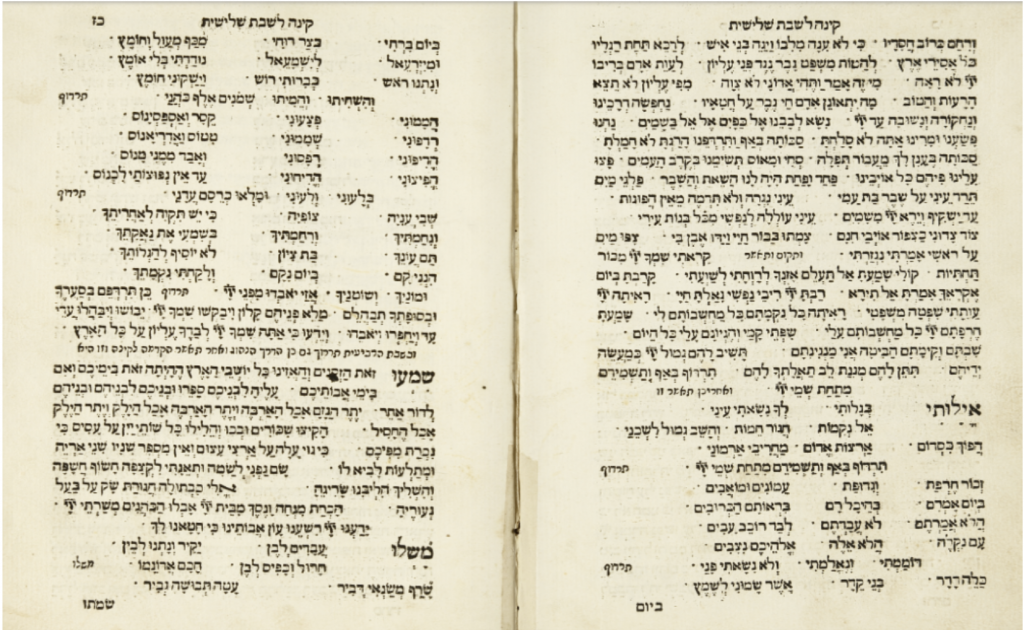

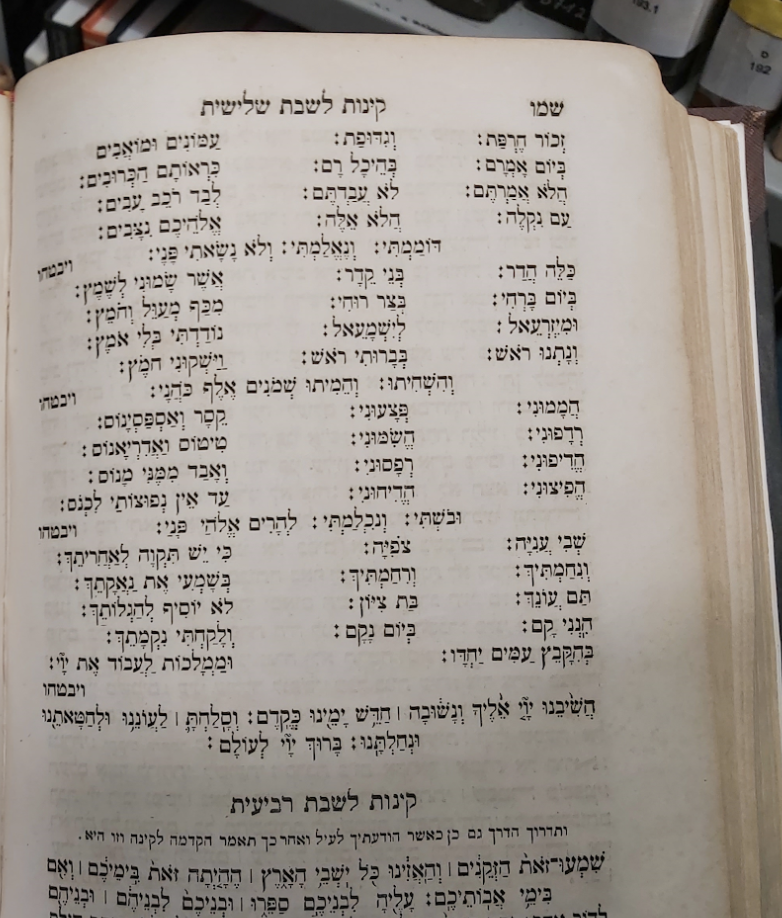

Karaite Siddur, Vilna 1868 (this is the book that Dubsewitz was using):

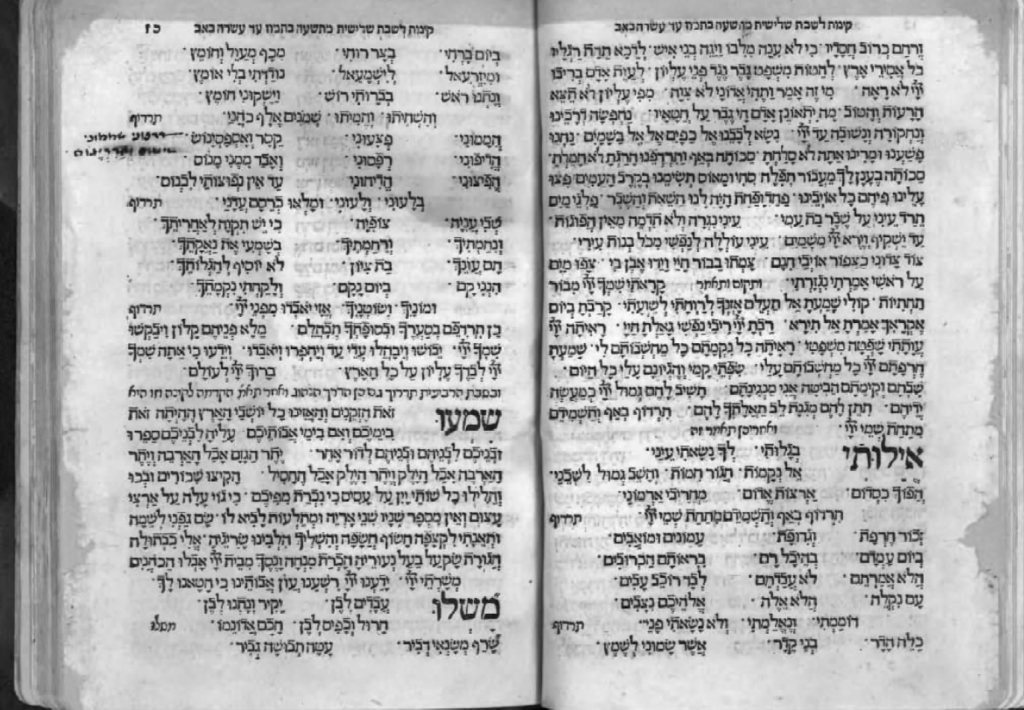

Karaite Siddur, Vilna 1891:

Abraham Dov (Baer) Dubsewitz of Kiev, “One facing the other”, in Dubsewitz, בחדא מחתא (= At One Stroke: Seven Separate Articles, Cracow 1888):

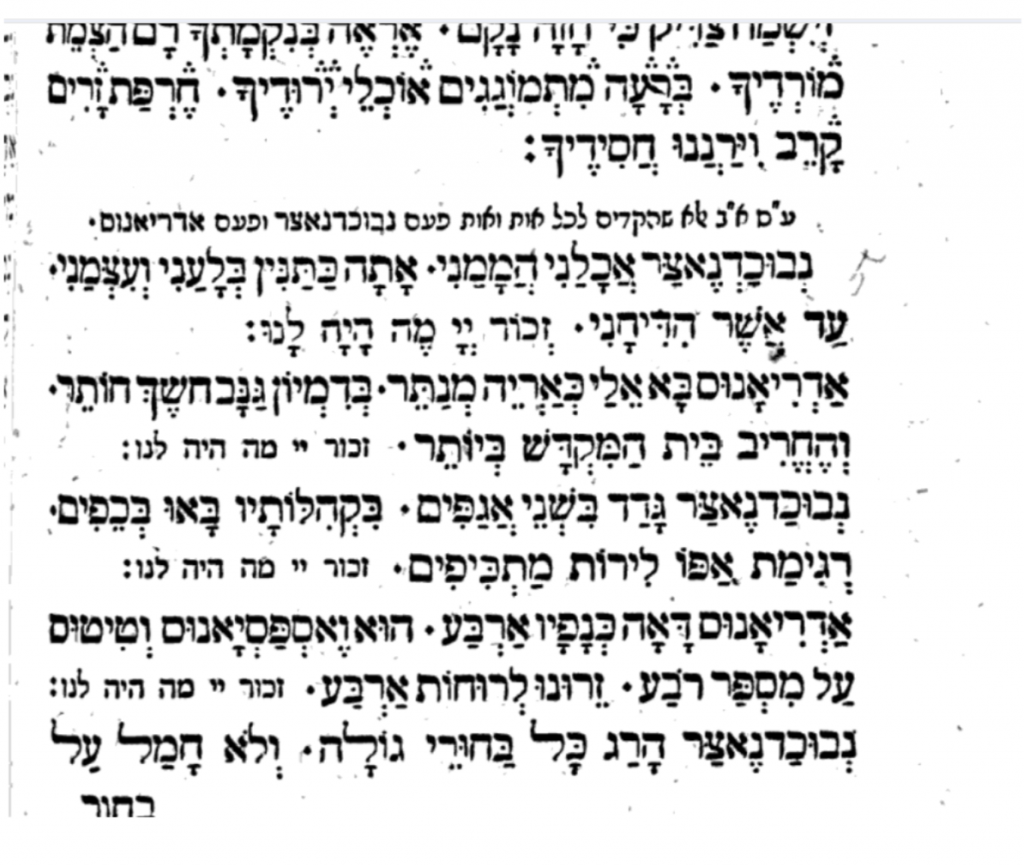

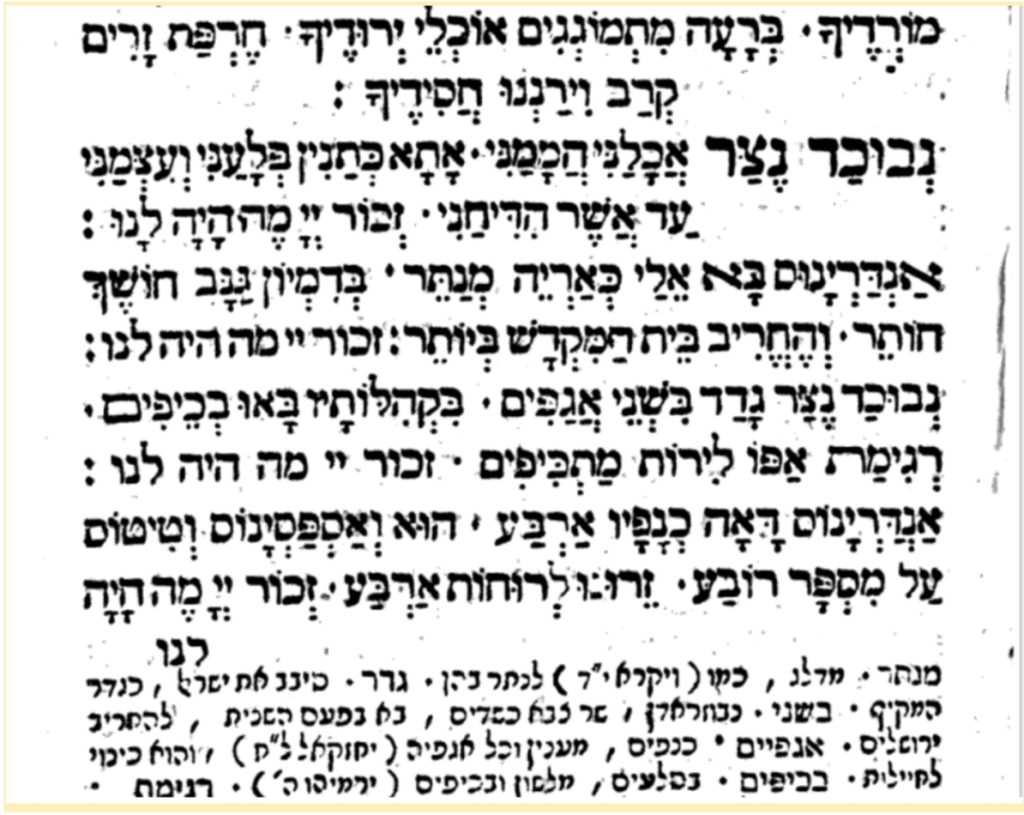

For comparison, here are the opening stanzas of the poem Nevukhadnetzar Akhalani, which is recited in some Rabbanite rites on the Ninth of Av. Here’s a mahzor printed in Fürth in 1811:

Note that one line above the bottom line of the page, it says: הוּא וְאַסְפַּסְיָנוֹס וְטִיטוֹס: “He, and Aspasyanos, and Titos” (hu, ve’aspasyanos, vetitos).

Now let’s look at an edition printed just fifteen years later (1826), in Rödelheim, edited by Wolff Heidenheim, a very aggressive editor, and very scholarly — some might argue too scholarly. He knew Greek and Latin, and knew that the Latin form of the name was not Aspasianus, but Vespasianus. How would he sneak this “more correct” (but foreign to Hebrew) form into his mahzor? He took advantage of the fact that the word had the conjunction ve- (“and”) in the poem, and revocalized the word such that the letter ve– formed not the conjunction, but part of the name, and thus the line became: “He, Vespasyanos, and Titos” (hu, vespasyanos, vetitos; three lines from the bottom of the page):

The editor of the 1891 Vilna mahzor played the same trick on the text of “Eyaluti Begaluti”; it is likely that this editor was familiar with Heidenheim’s work, from 65 years later, and noticed the trick that Heidenheim had played on the text of “Nevukhadnetzar Akhalani”, and intentionally wanted to copy the trick, in the name of Correct Latin.

* * *

[1] This letter is by the Rabbanite Sage Shadal (Samuel David Luzzatto) to Leopold Dukes, dated 12 November 1838. Shadal corresponded with the great Jewish scholars of Europe of his day: Zunz, Baer, Graetz, and many more. Because Shadal had access to many manuscripts, he would often copy out whole texts from the manuscripts in his letters to his colleagues. After his death, Shadal’s letters were published — and in many cases, these are the only publications of a text that is otherwise known only from manuscripts!

Shawn,

There is a tech censorship issue by you tube and we are unable to listen to the poem. “This video has been removed for violating YouTube’s Terms of Service”.

Can you place it elsewhere for us to hear?

Kudos to you and to Dr. Wasserman and to Rotem for the poetic and literary forensics that have been conducted here on this work! and once again Thank You for bringing it for our enlightenment.

L’Shalom

May your 7th and 10th of Av Lamentations be meaningful.

I have updated and placed the song separately.

Shavu`a Ṭov.

While you loathe printing liturgically any poem that calls for the destruction of *any* people or population, we all need to be on the same page about the accuracy of translation. This is why I believe the line

כַּלֵּה הֲדַר : בְּנֵי קֵדָר : אֲשֶׁר שָׂמוּנִי לְשֶׁמֶץ

was not accurately translated by rendering it “Destroy the glory of the Kedarites, who made me an object of scorn”.

At the very least, the rendition of Kaleh Hadar as “destroy the glory” is a gross inaccuracy. A more accurate rendition is “finish the glory”.

I wish to note emphatically though that even the statement “destroy the glory” is a far cry from a call to exterminate the Muslims. To determine the opposite is the case may well be politically correct (much to the delight of antisemites and others who do not have our best interests at heart), but it is a lie.

I am Brazilian, a descendant of Sephardic Jews (Bnei Anussim) and Ashquenasim Jews.

I live Judaism as Reform Judaism. What I love most about the Reformation is the freedom to decide on the so-called truth of the wise( doctrine rabanite)

I beginned reading about the Karaites and I fell in love. You live without a fixed rule, and you use the freedom of interpretation of the texts, just what I look for in Reform Judaism.

I really liked this song. I’m subscribed to your YouTube channel.

My sincere opinion is that you show love for your neighbor by preferring to “adulterate” old poetry to remove “expressions of hatred”.

I am conservative in many ways. I believe you can remove it from the official music, but leave a note explaining the reason, as well as preserve the original poetry in a footnote, or as an appendix to Sidur.

If 19th century karaites did this, you would know exactly when the text was repaired and what the text was like before “correction”.

Despite the harsh words to destroy, Tanach “contains passages like this (Tehilim 137).

I am not Karaita (in Brazil there are no Karaites) but I think not to completely erase this poetry. Although tough, it is part of your story. The words of vengeance are part of Jewish history (see Birkat Haminim). They preserve the feeling of our brothers who suffered at different times such as Crusades, Inquisition, Pogrons, etc.

Amazing , thank you!

So

I wonder what changed to make it unacceptable to call for the destruction of those anti-Semites who treat Jews badly?